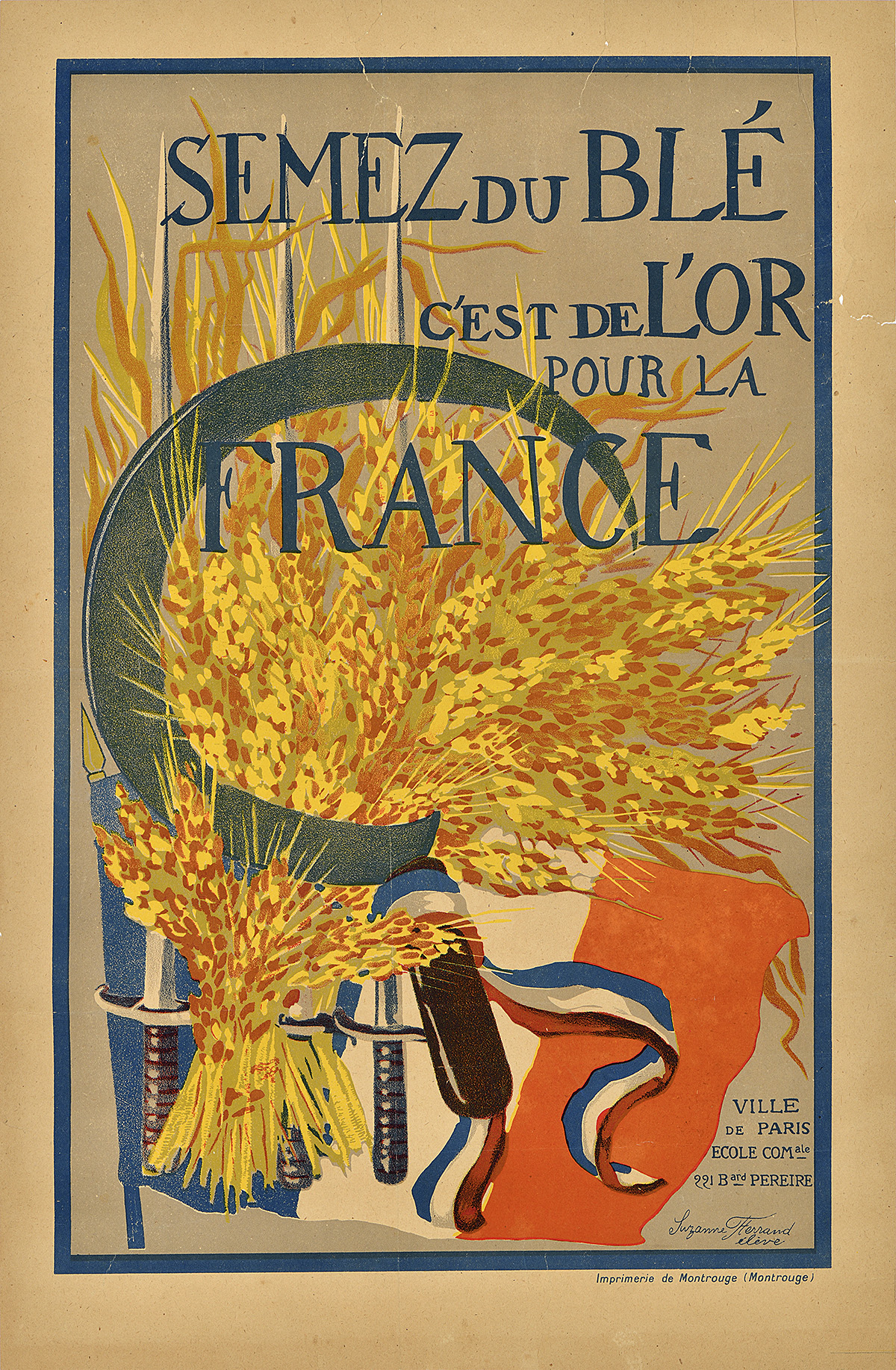

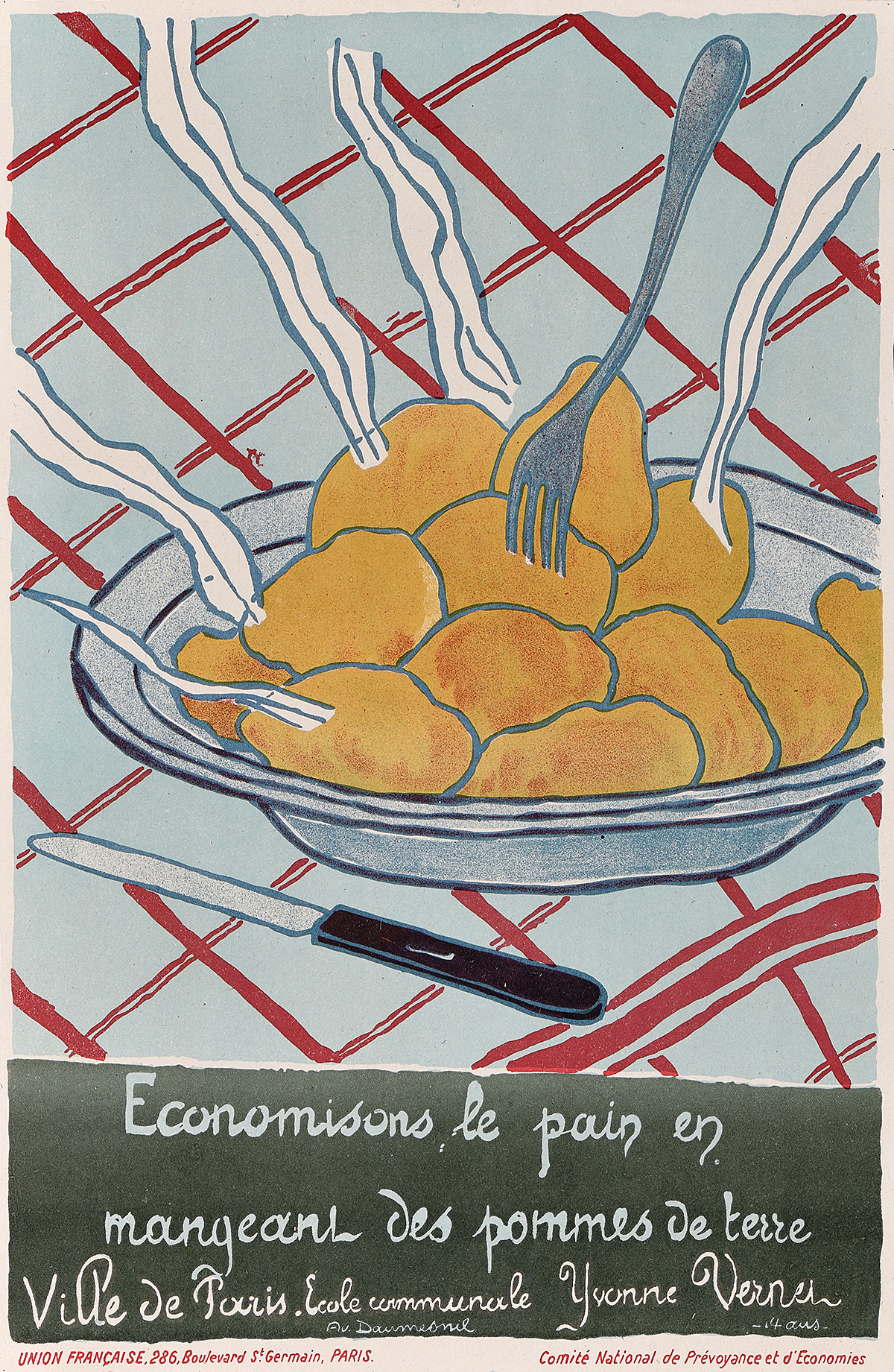

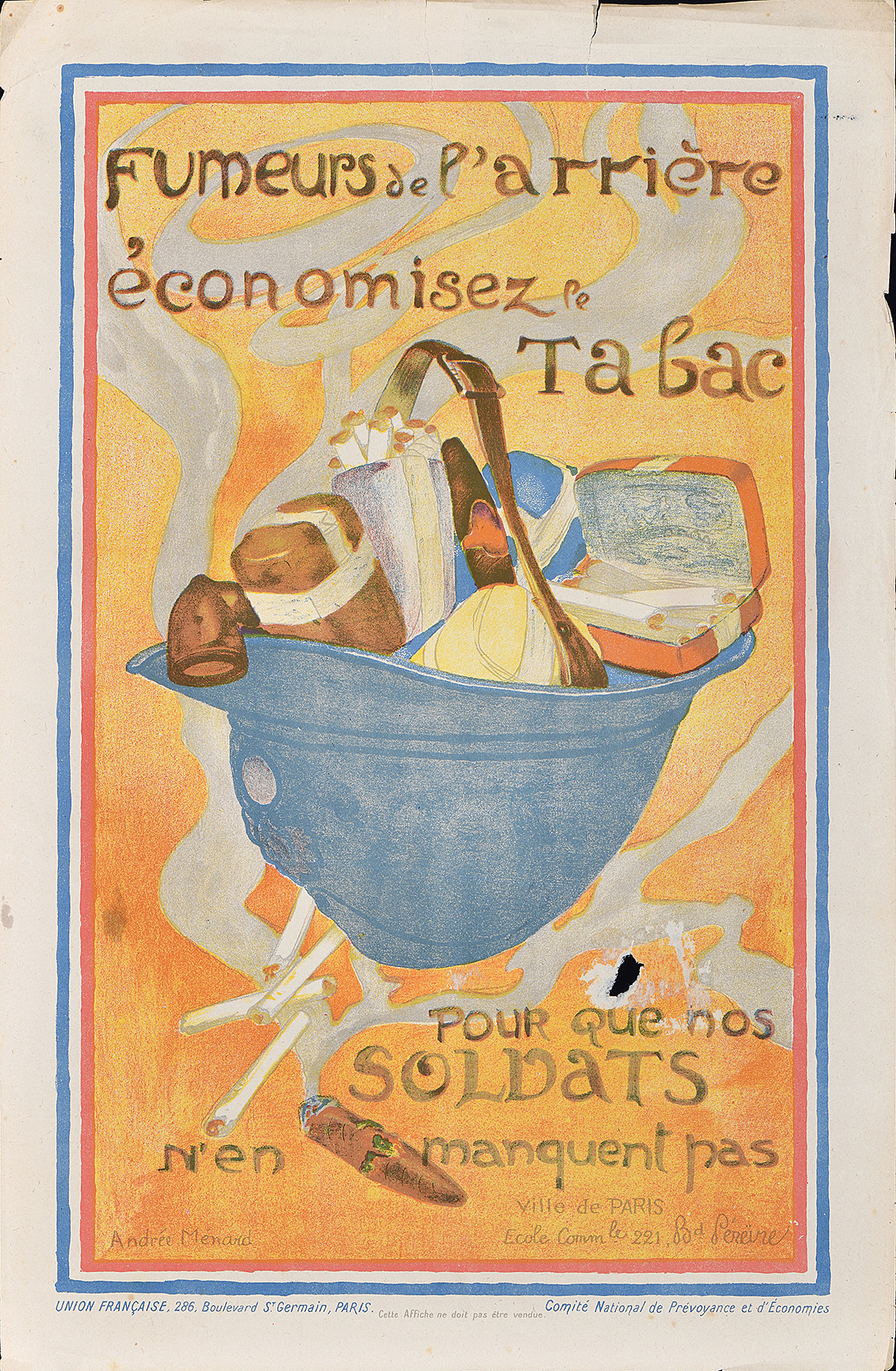

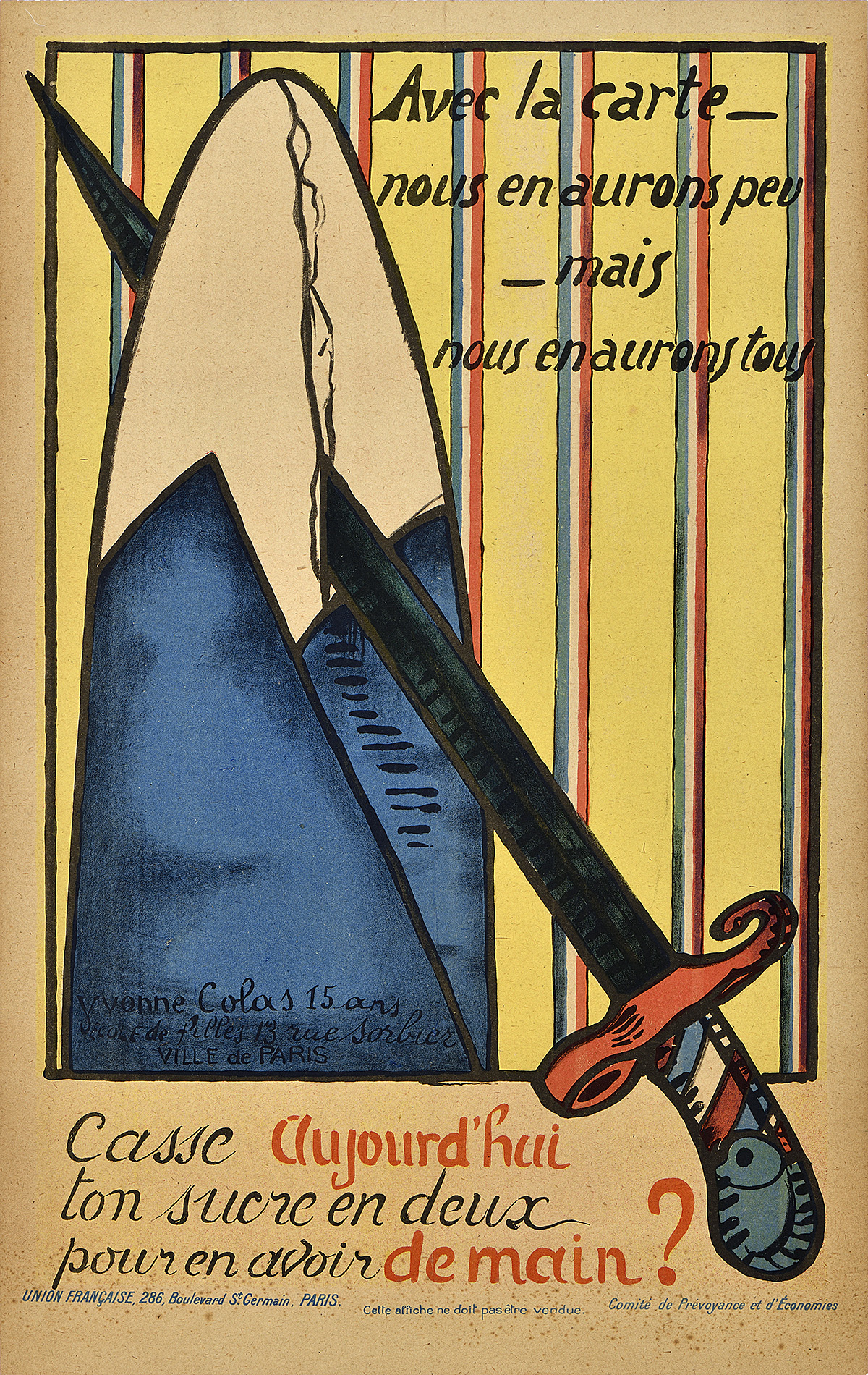

Schoolgirls at War: French Propaganda Posters from World War I

In a surprising move during the final year of World War I, the French government turned to Parisian schoolgirls to create propaganda posters directed at the general public. Up until this time, the country’s posters had been relatively colorless, focusing on the sacrifices being made by soldiers for the protection of women and children. By 1918, however, the weary and bereft French people had become increasingly jaded, and much less likely to be swayed by such guilt-inducing messaging. Since the beginning of the war in August 1914, half of its male population between the ages of 15 and 30 had been killed and more than 1.1 million children had been orphaned. Crippling shortages of food and materials, combined with the loss of income from men in service, meant that most families were struggling to survive. As many mothers now had to work, essential goods were obtained by children tasked with standing in lines for hours before presenting ration cards to shopkeepers in return for their families’ meager allotments. Further, strikes (often led by women workers) protesting the rising cost of living disrupted major French cities. The government had to find a new way to inspire solidarity among its citizens.

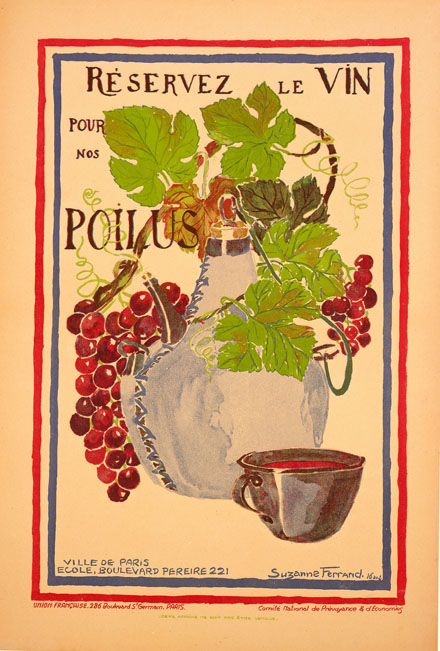

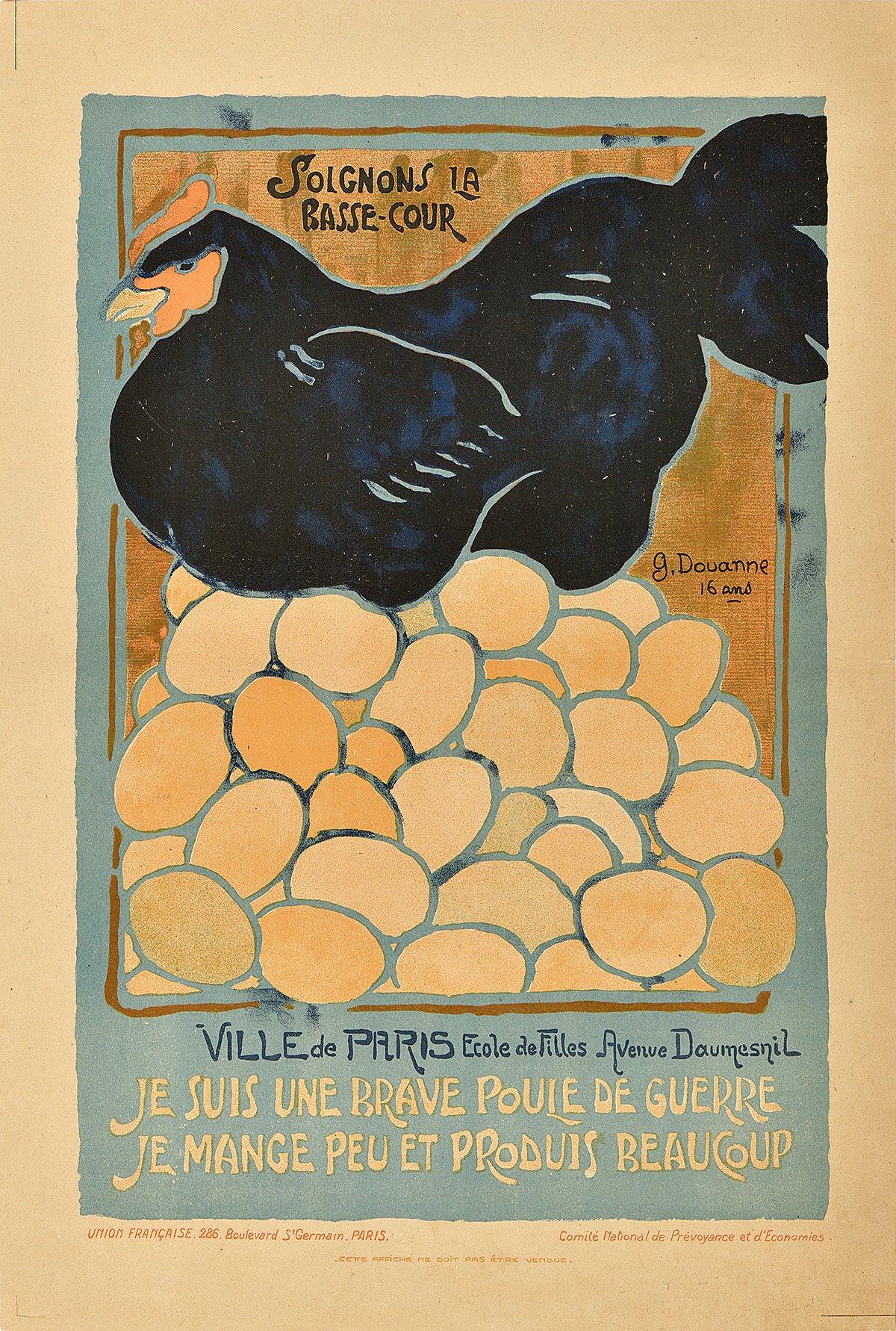

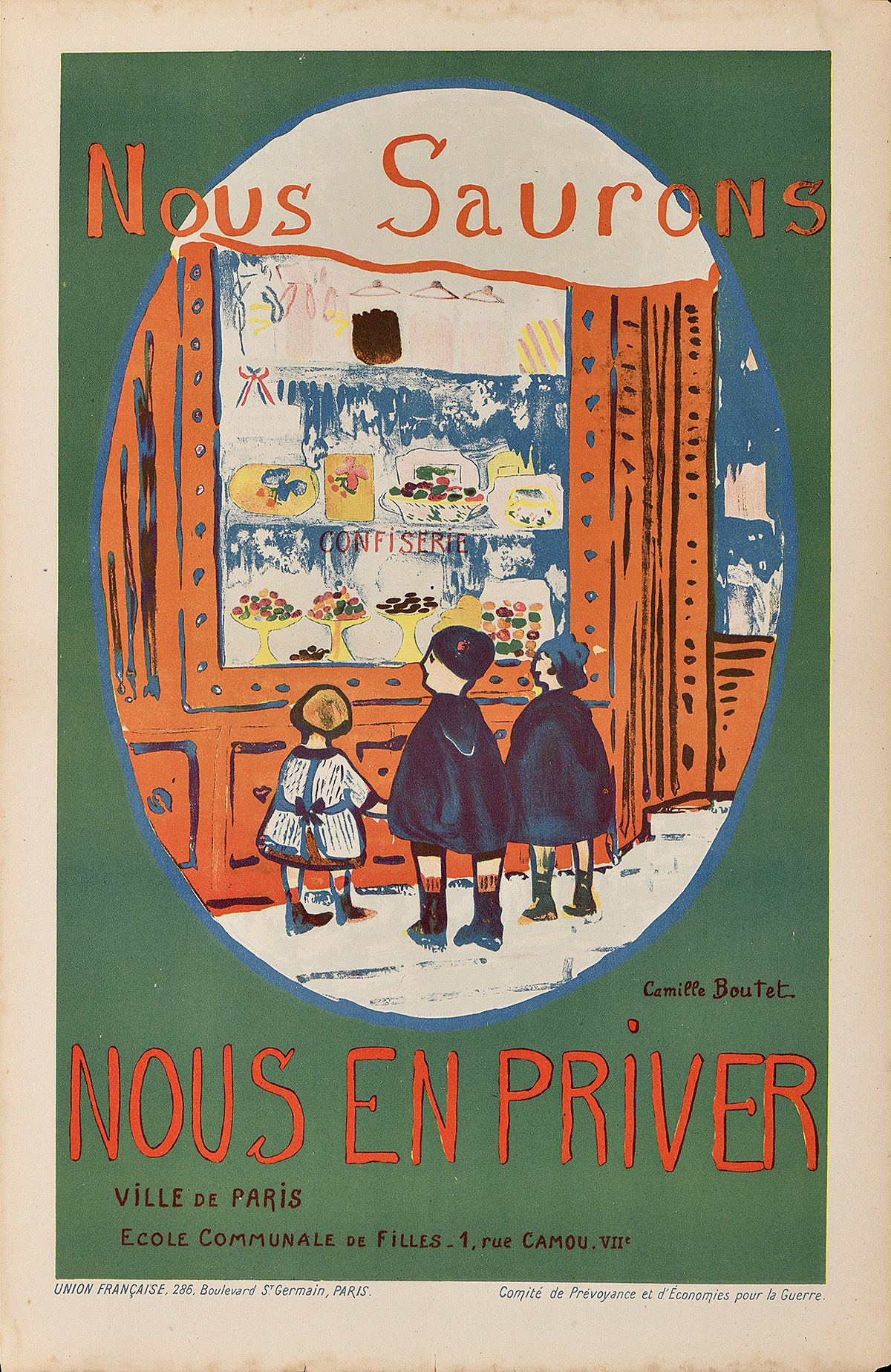

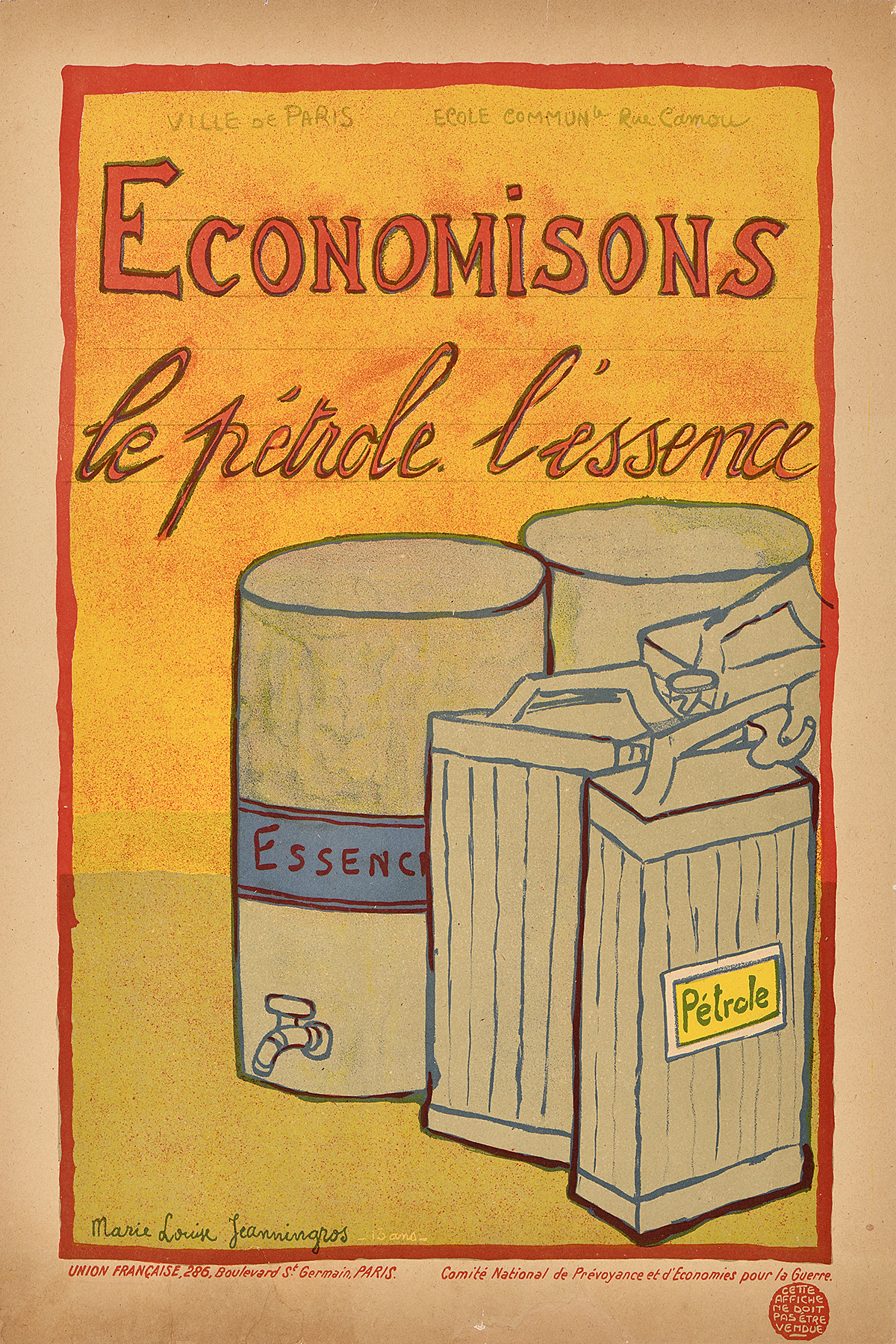

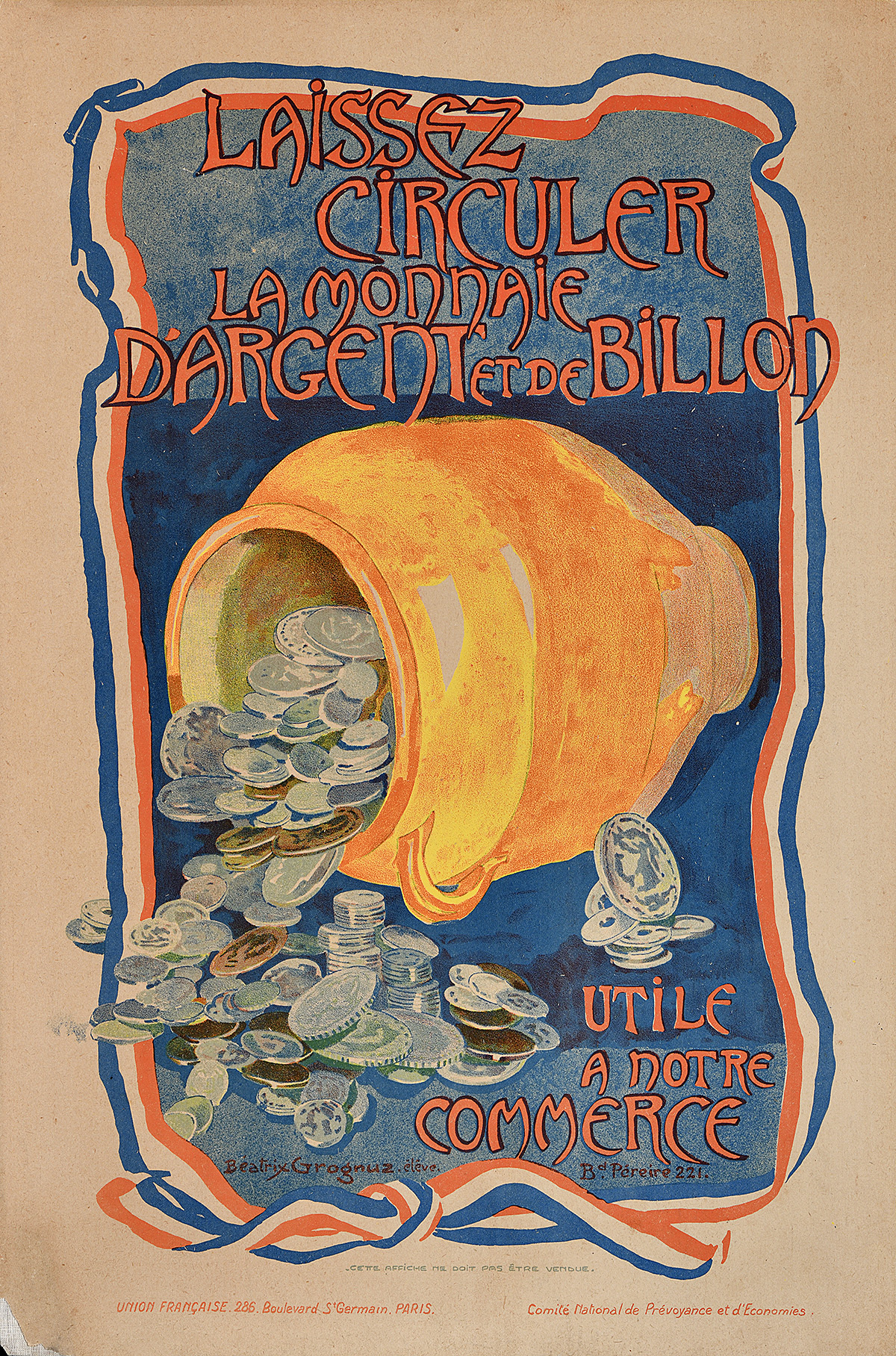

In June of 1917, Victor Boret, the minister of provisions, saw an exhibition of children’s prints on themes of war. Recognizing the potential of these images, he suggested to the government that posters made by young people might be the most effective way to encourage the French population to conserve resources. By early 1918, the Comité National de Prévoyance et d’Économies (National Committee for Foresight and Thrift) announced a student competition in Paris: the strongest designs on the theme of voluntary rationing would be printed and distributed throughout France. While hundreds of images were submitted, only 16 posters were finally printed—all drawn by girls between the ages of 13 and 16. At a time when young women were generally seen as no more than “future housewives,” and, in France, did not obtain the right to vote until 1944, the project represented a radical amplification of female voices.

The posters were a runaway success. The press celebrated their role in the apparent renewal of patriotic fervor in the adult population. Hundreds of thousands of the posters were printed and displayed in shop windows and post offices throughout Paris and the countryside, and many were sent to France’s allies for further distribution. Impressions on fine paper were also offered for sale in order to fund the war effort. These designs—some printed in seven colors—were costly to produce and received more fanfare and government promotion than almost any other official posters. During an era when a minuscule percentage of professional poster designers were women, this collection comprises the most significant number of female artists in the field. It also represents one of the most widely circulated French propaganda campaigns of the period.

Unless otherwise noted, all posters come from the Poster House Permanent Collection.