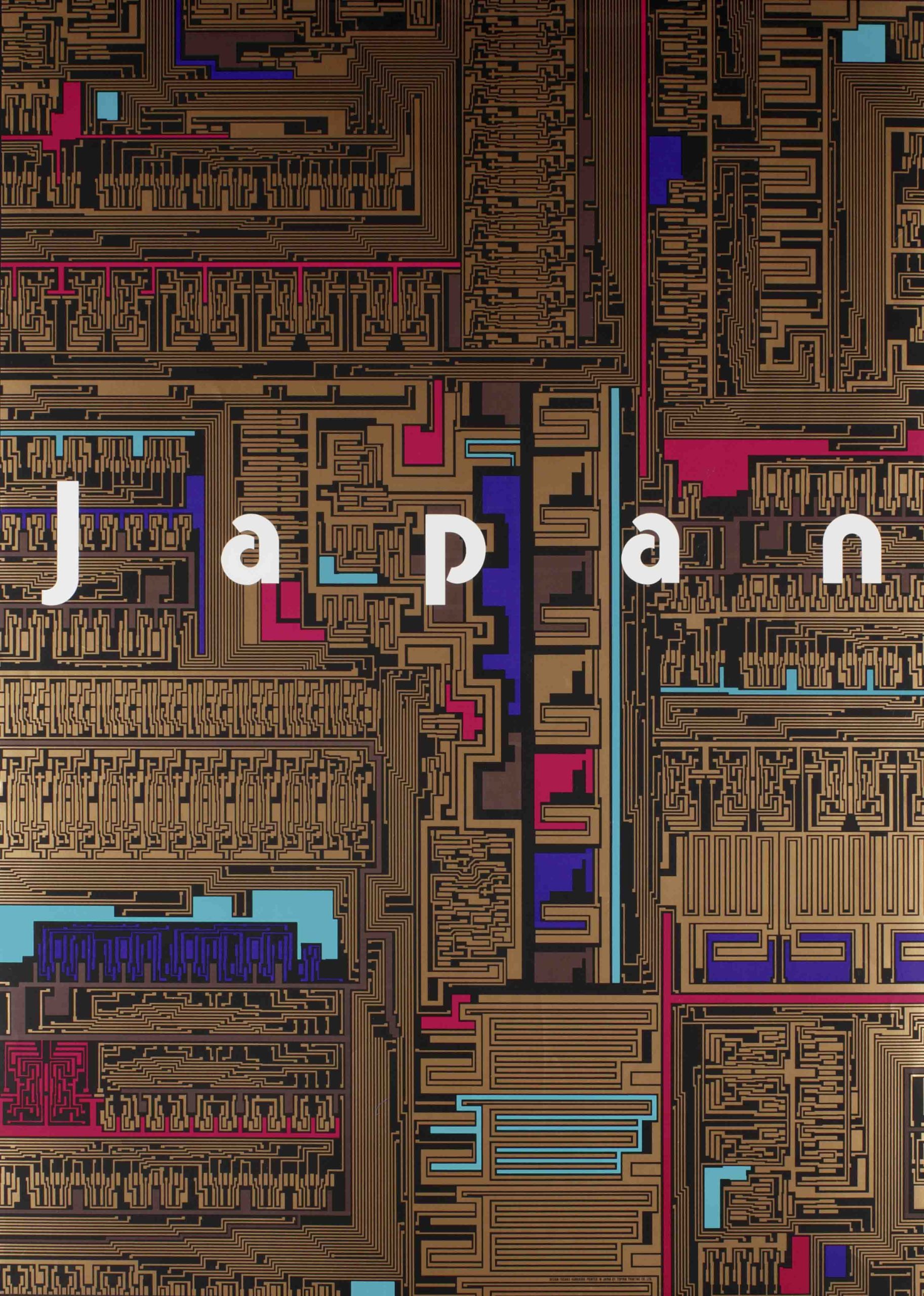

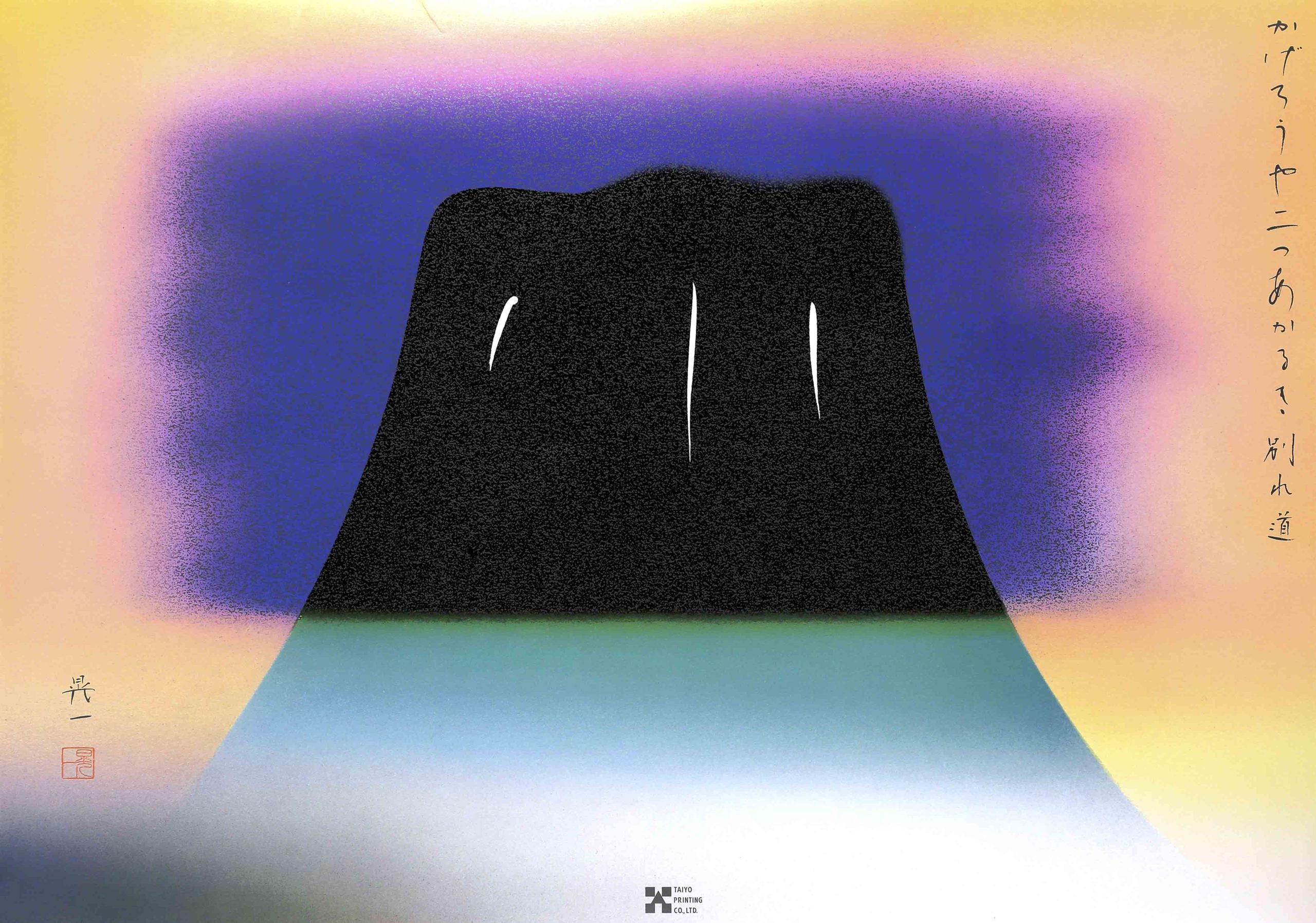

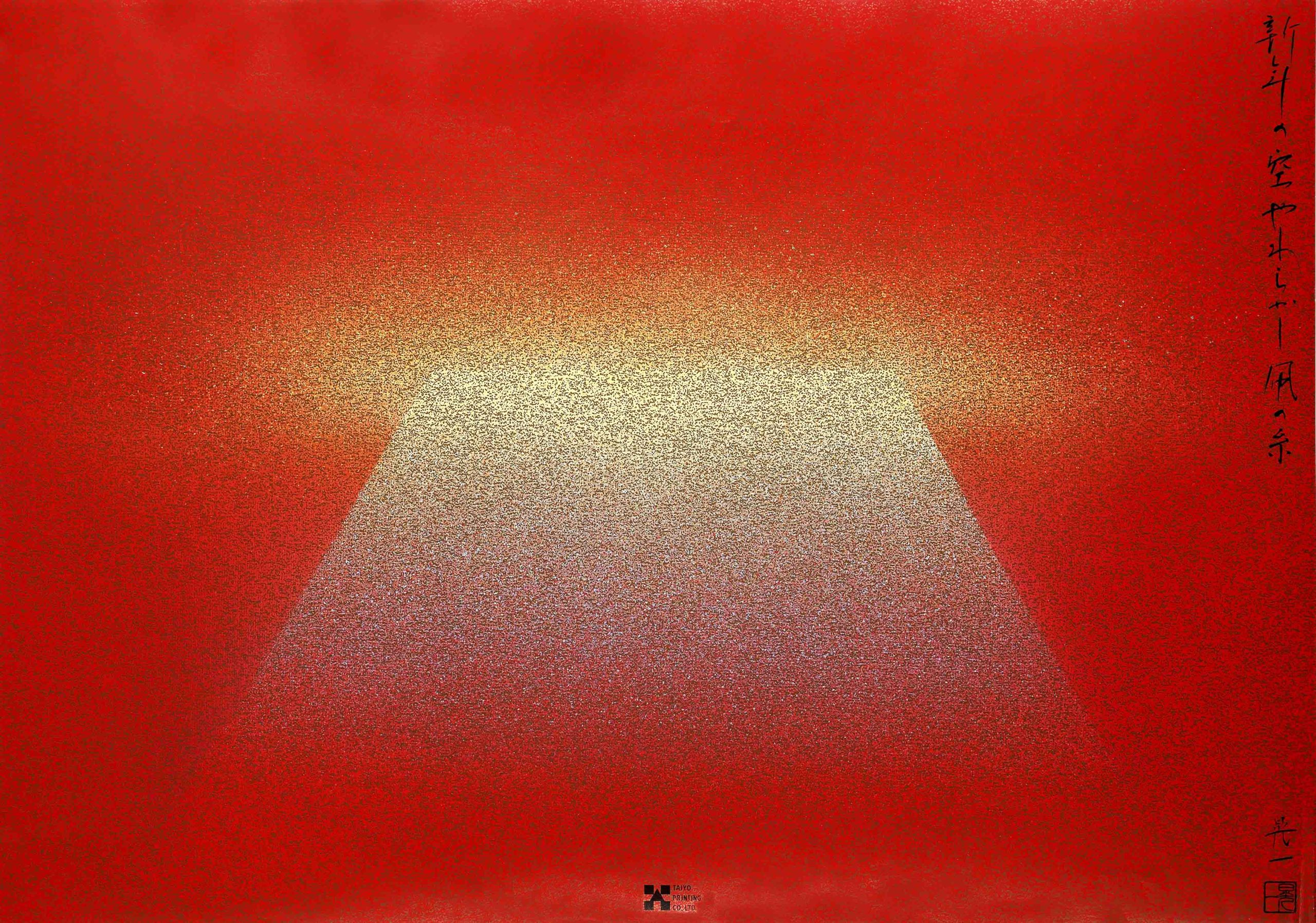

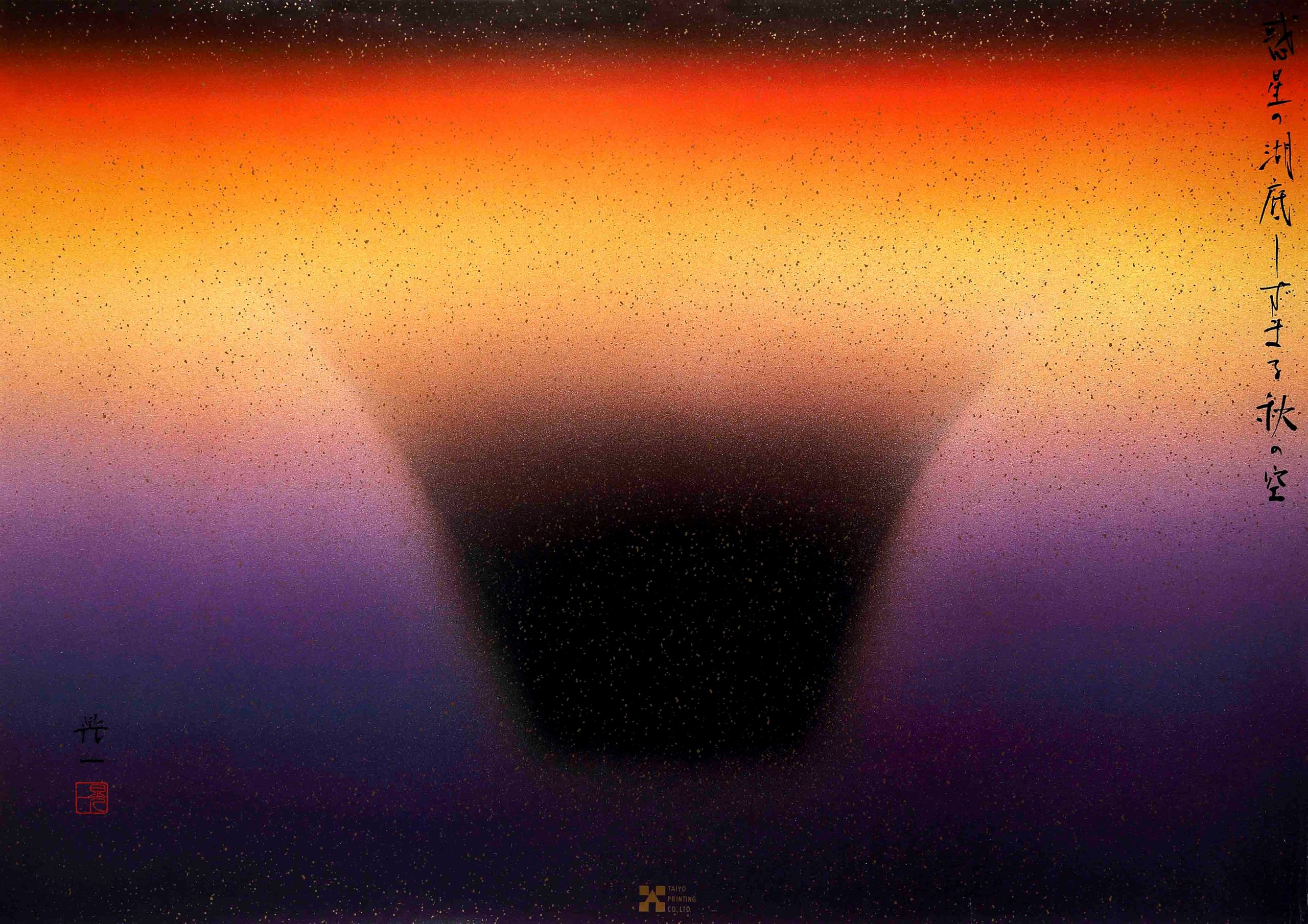

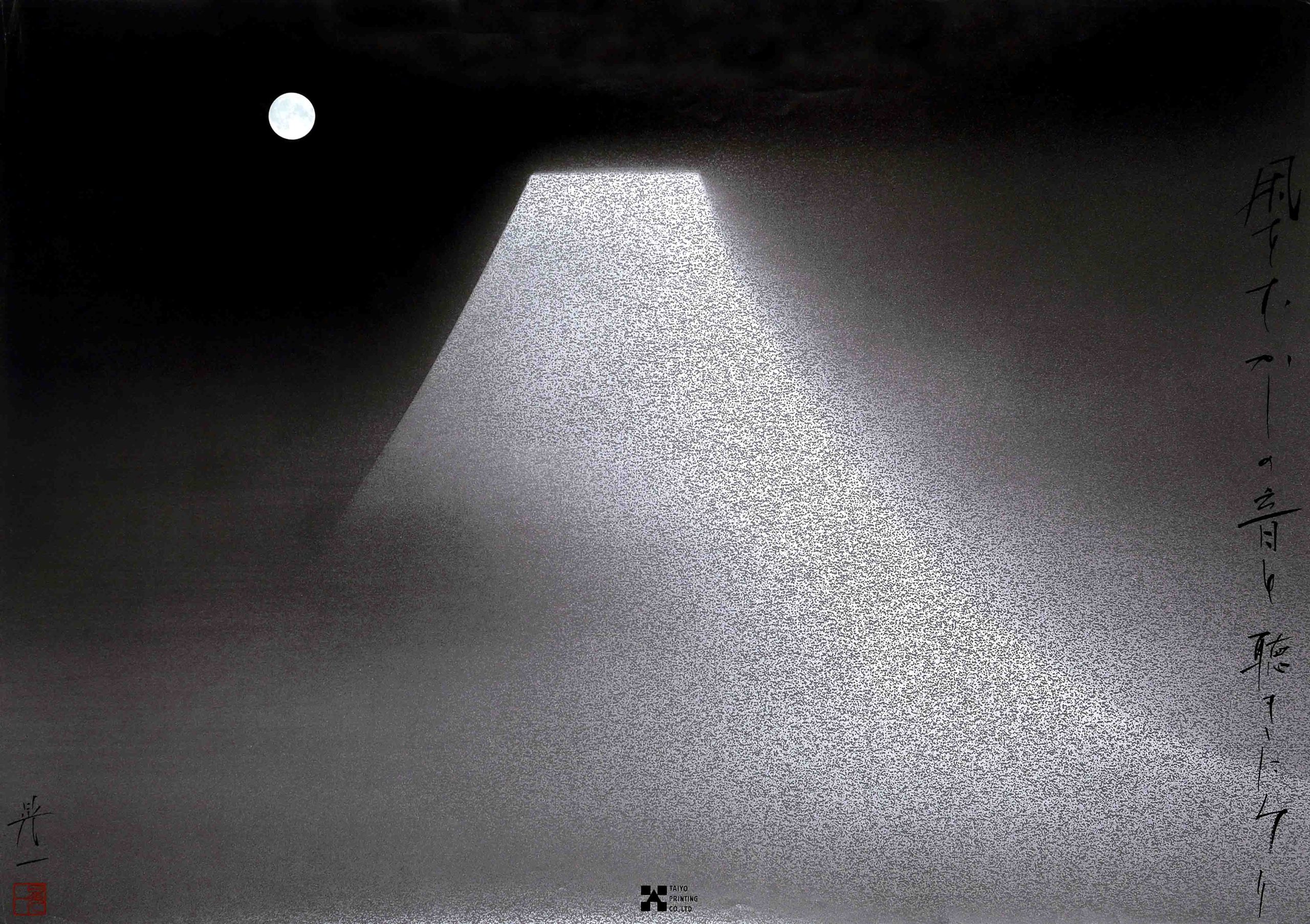

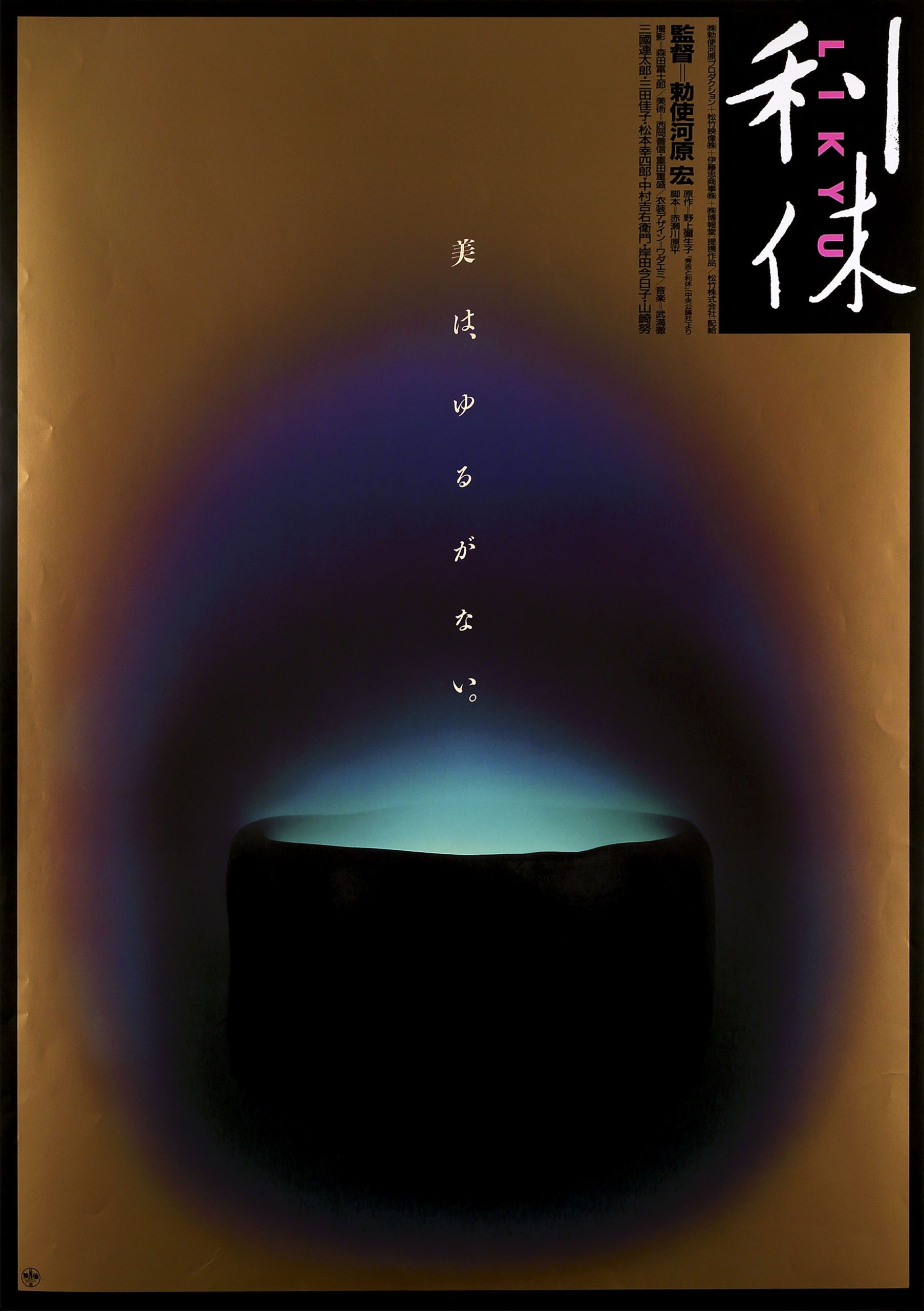

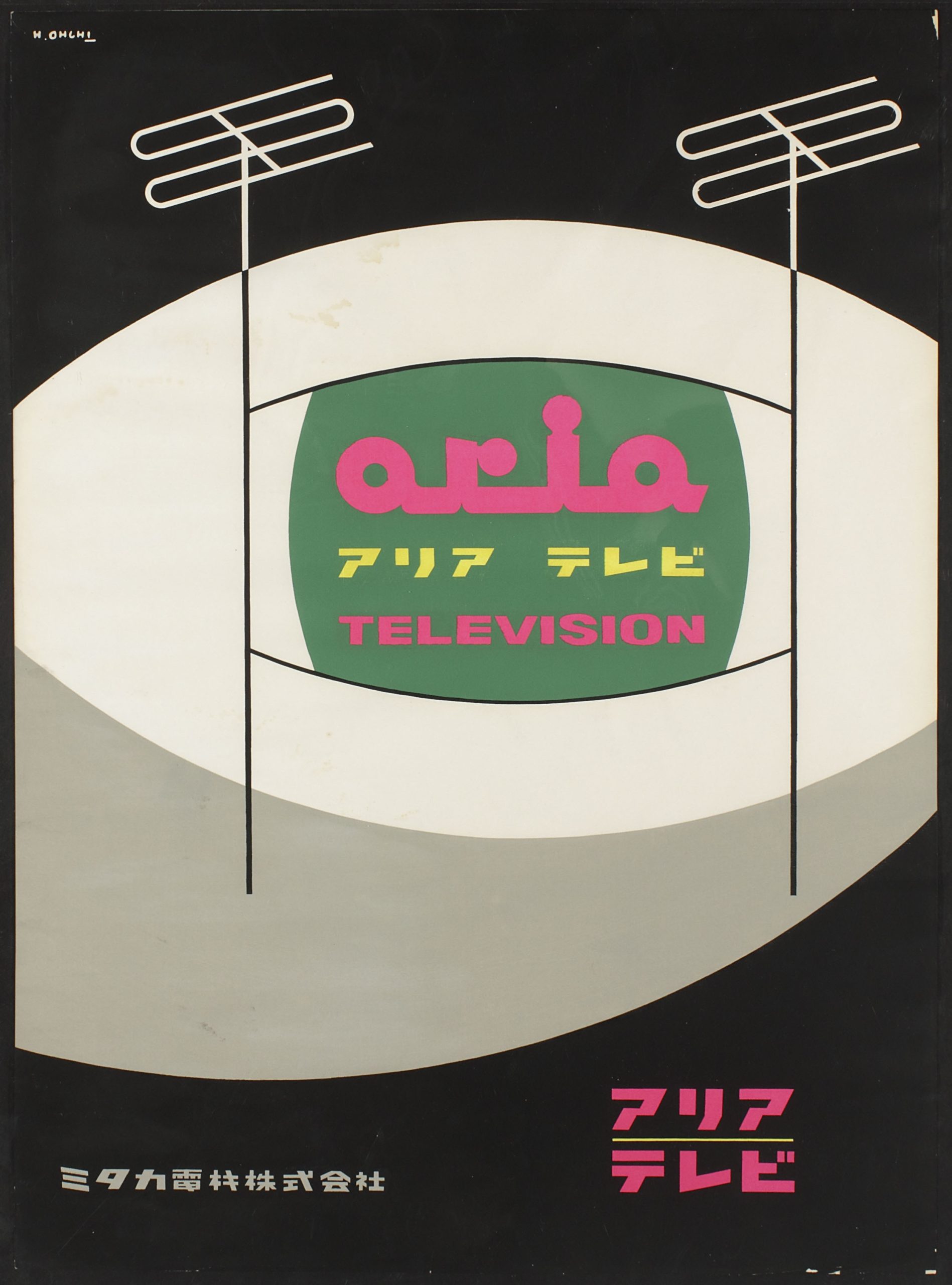

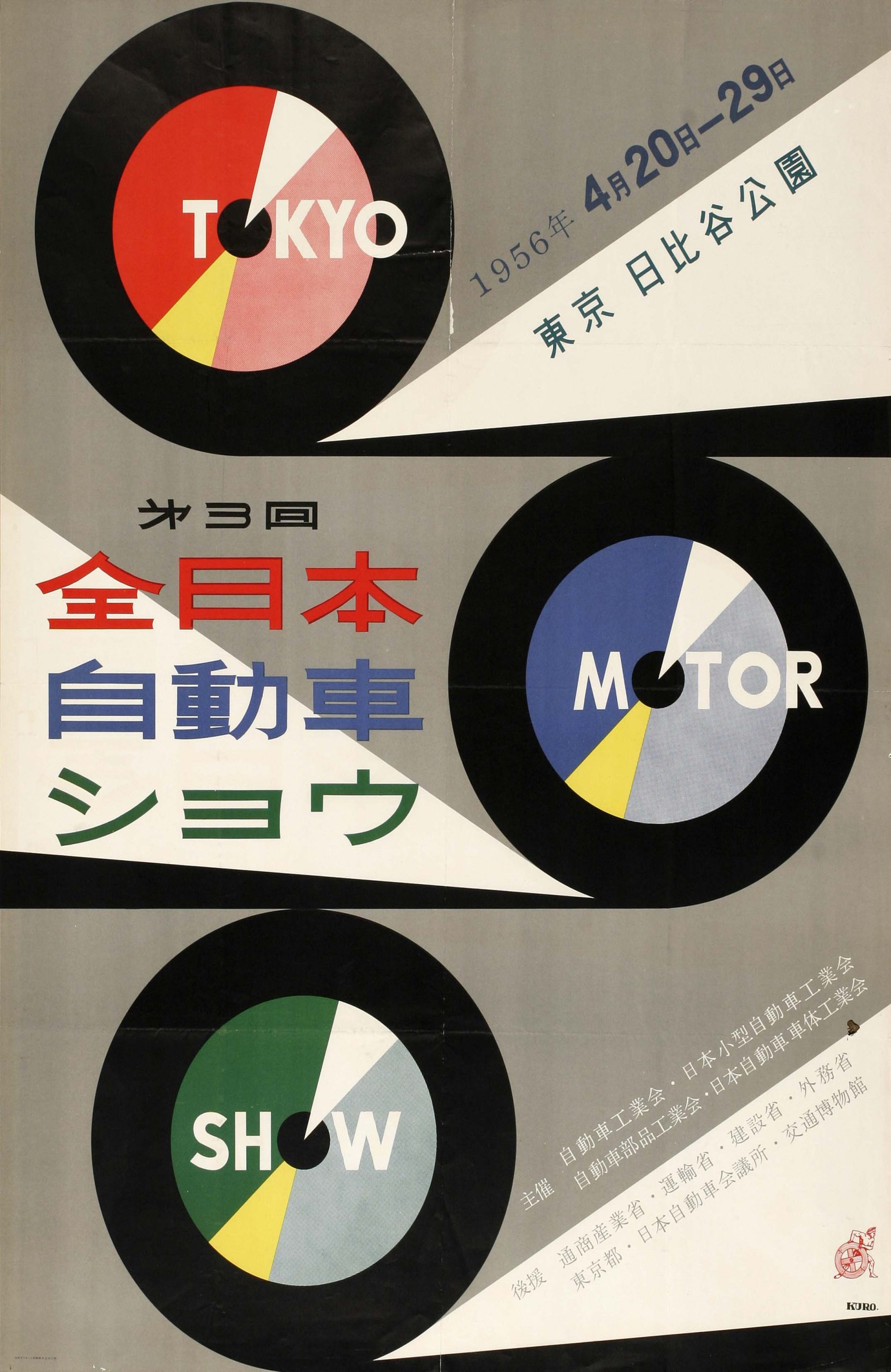

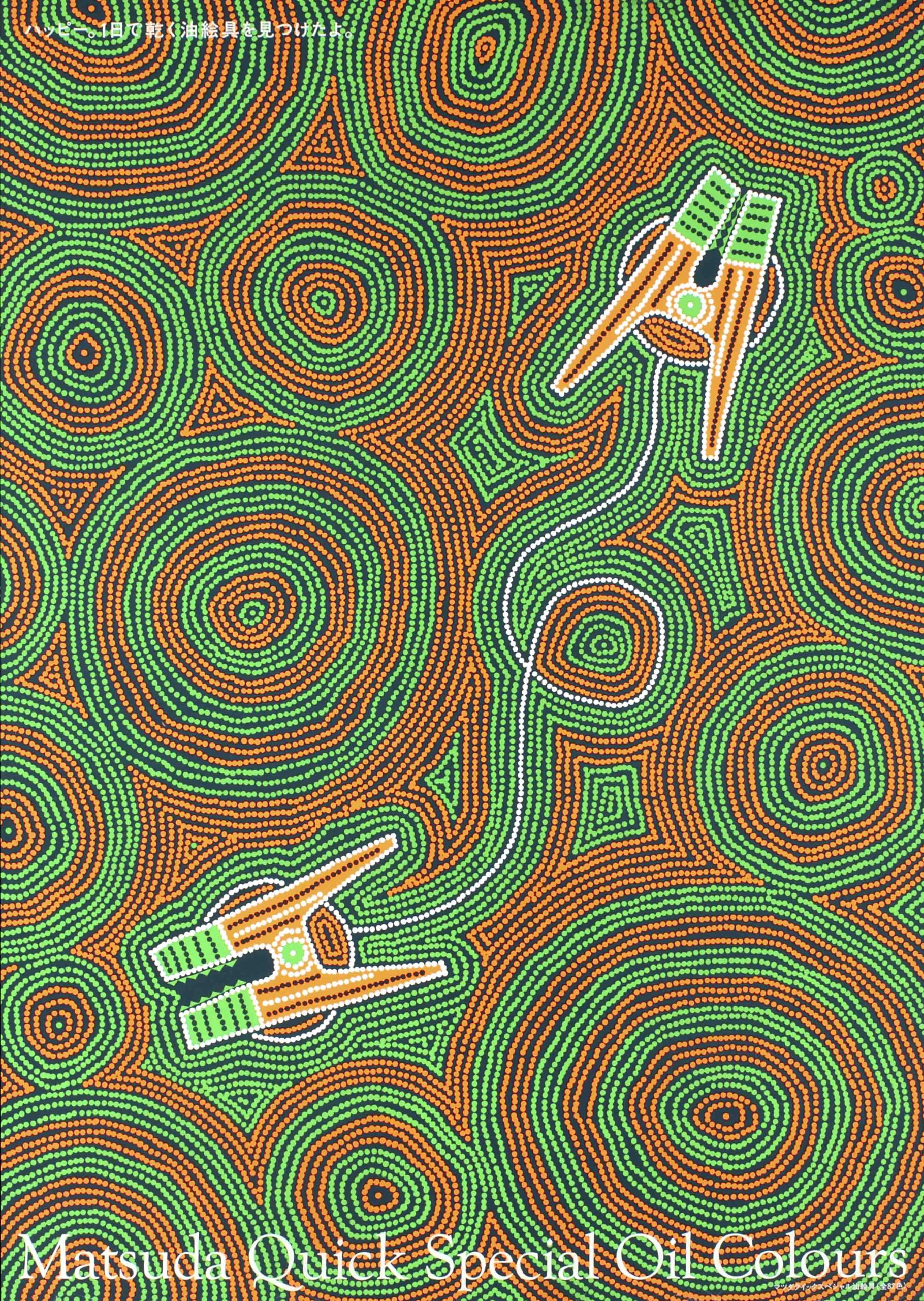

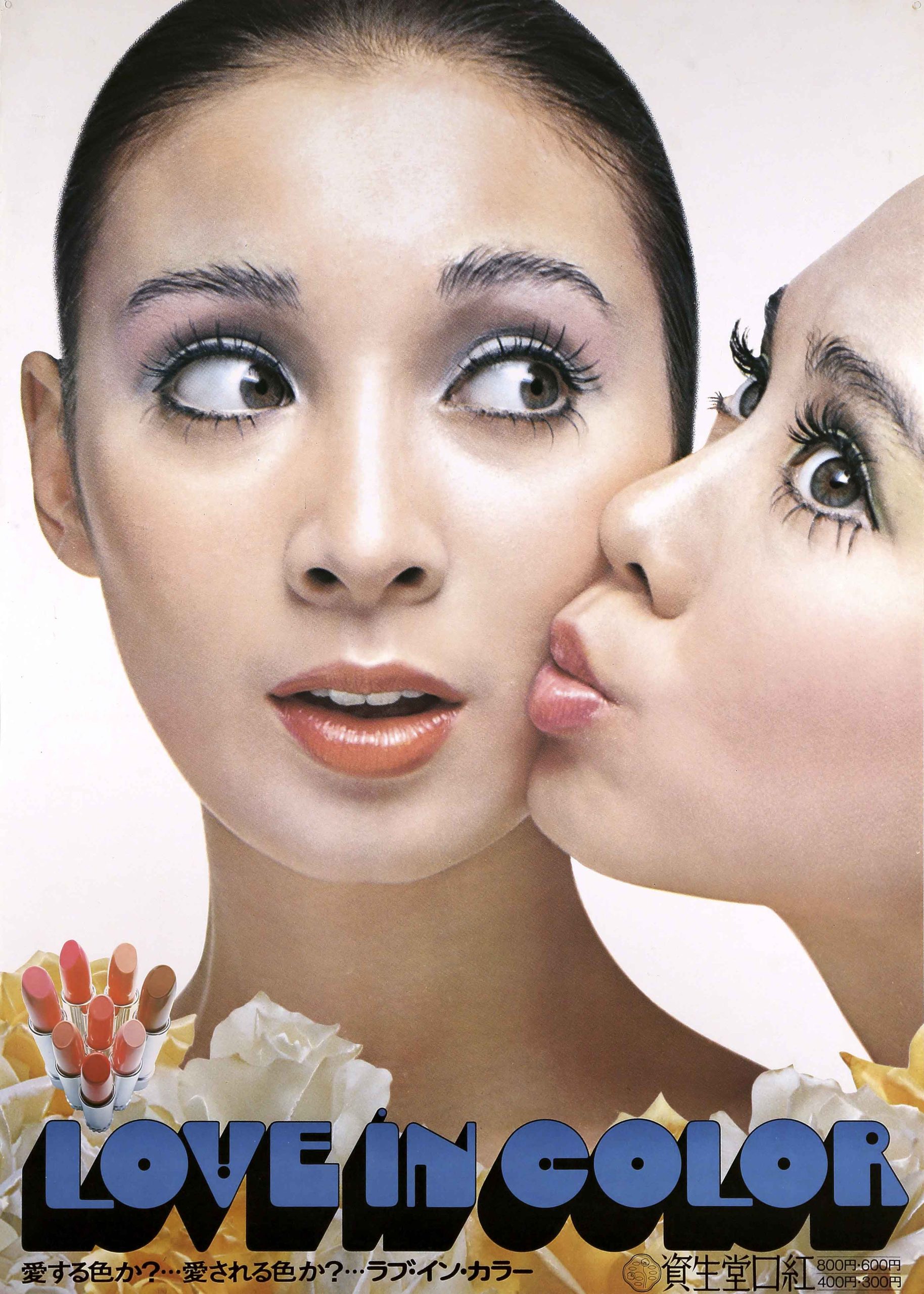

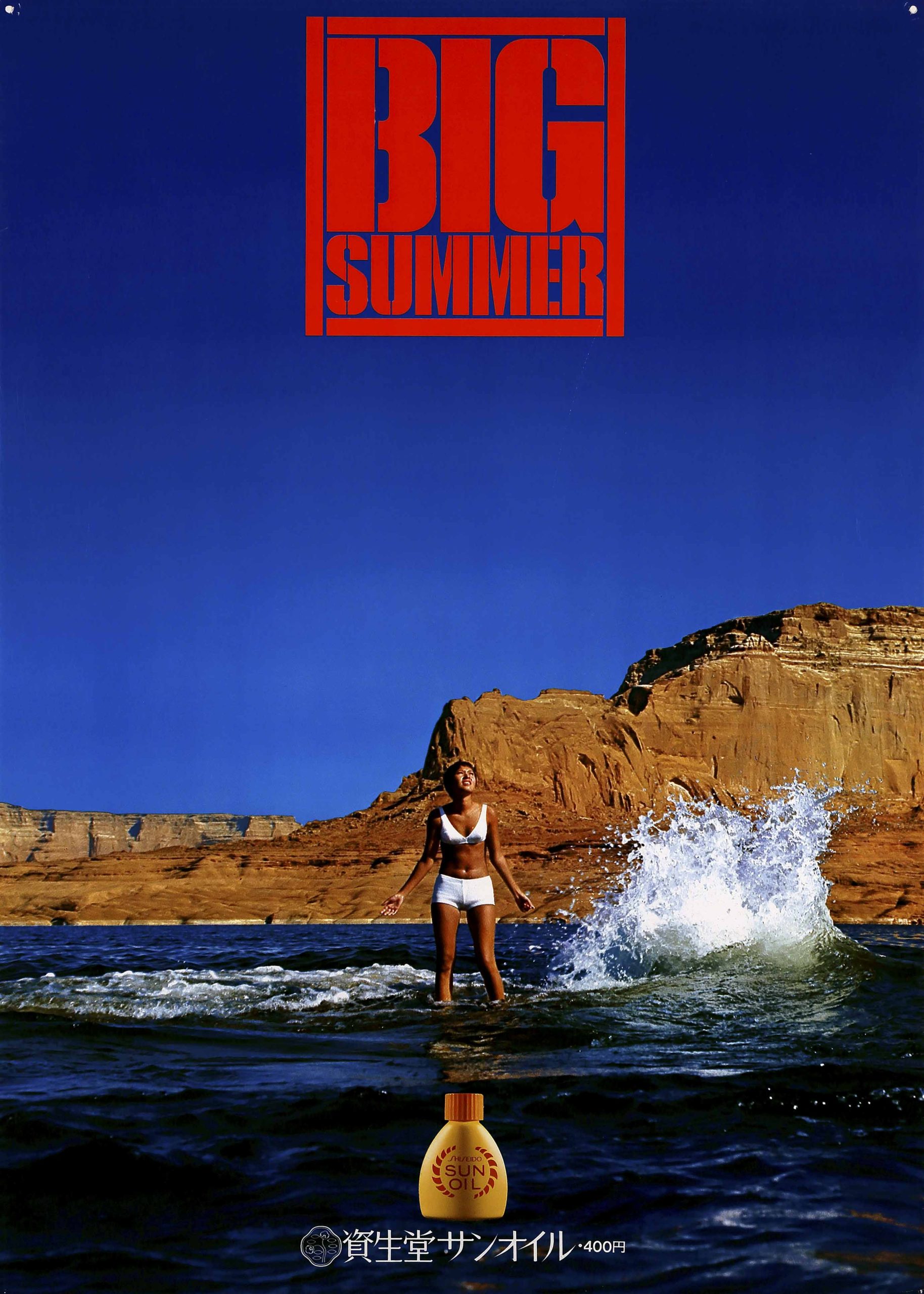

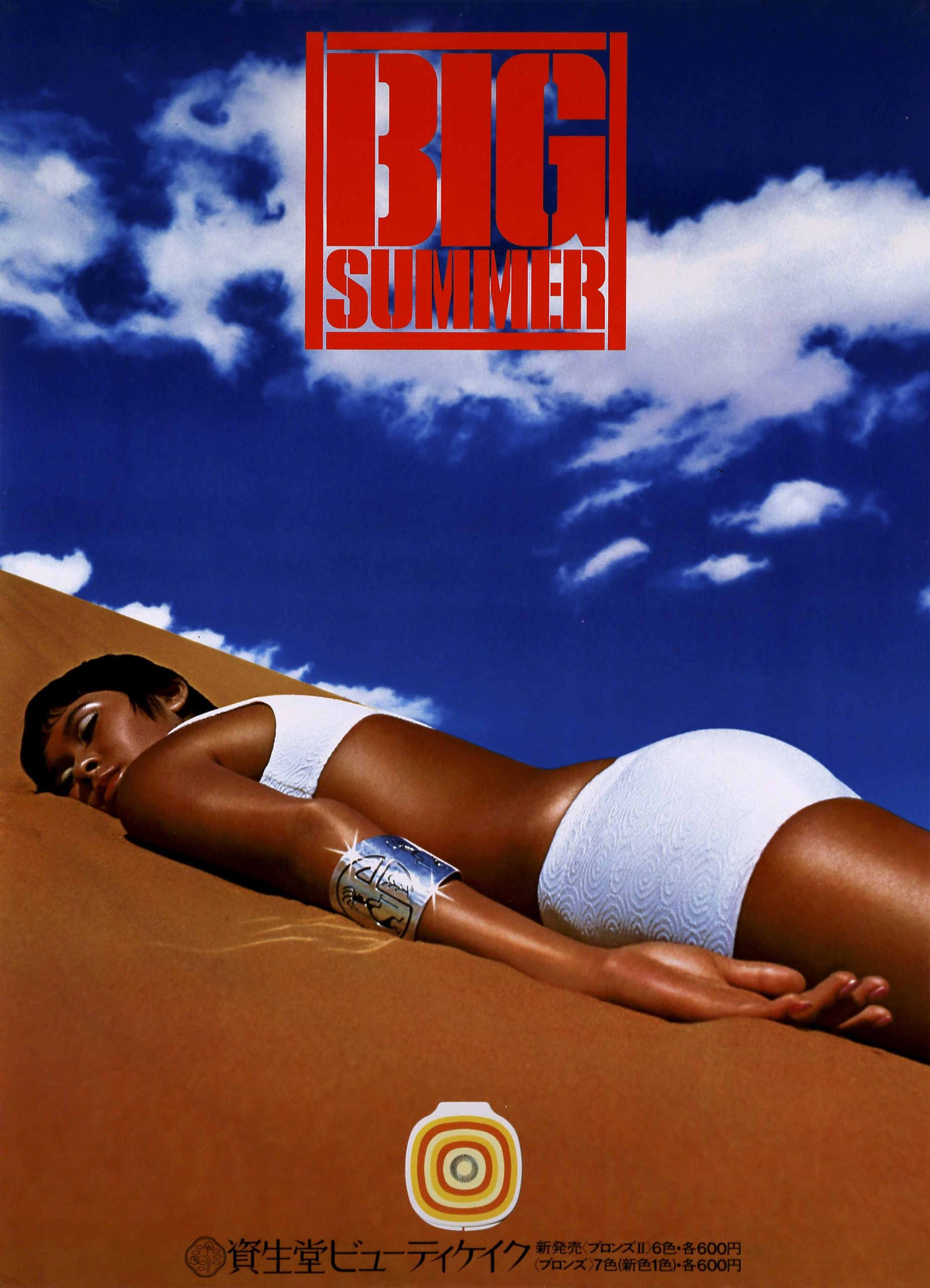

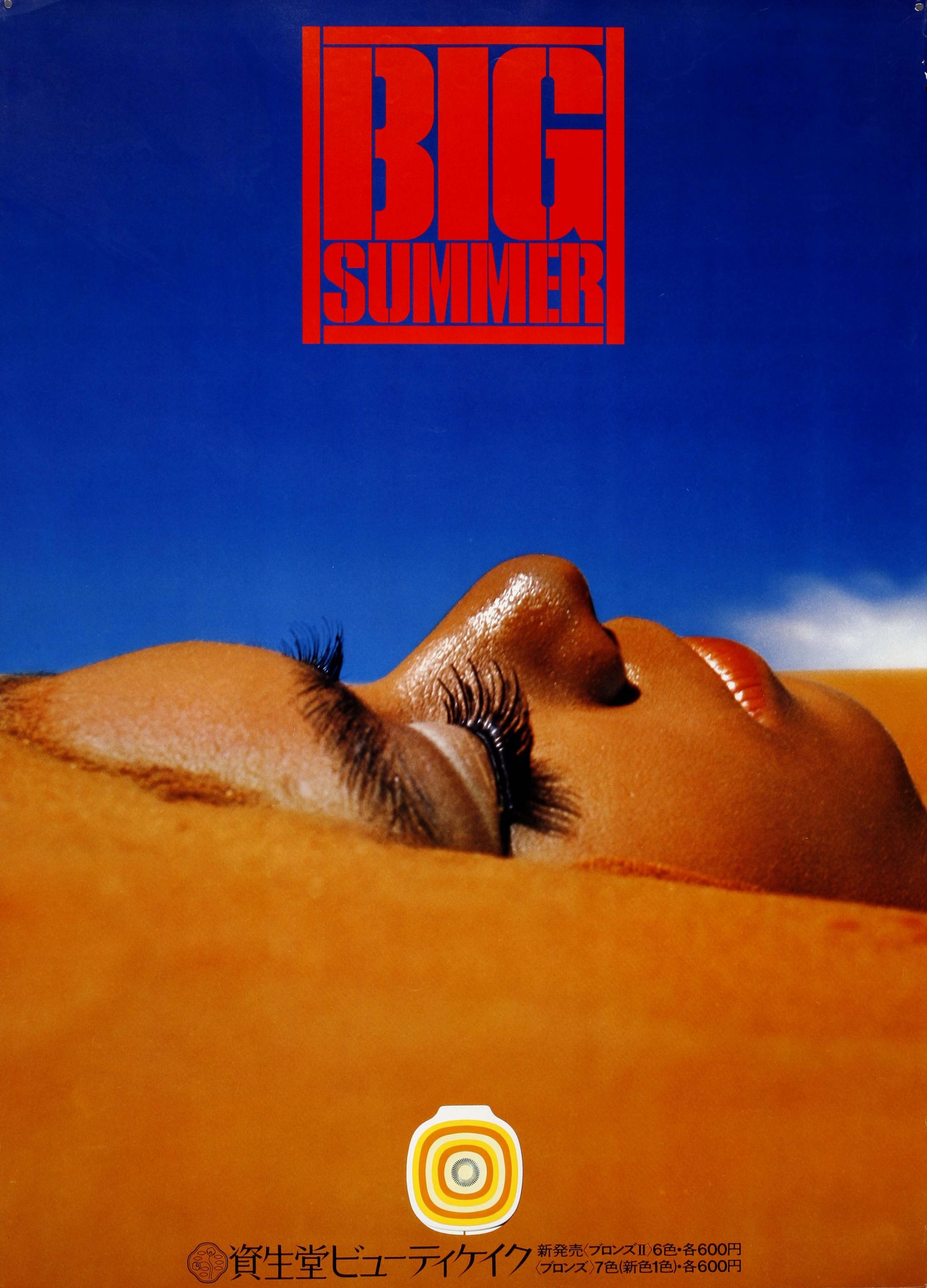

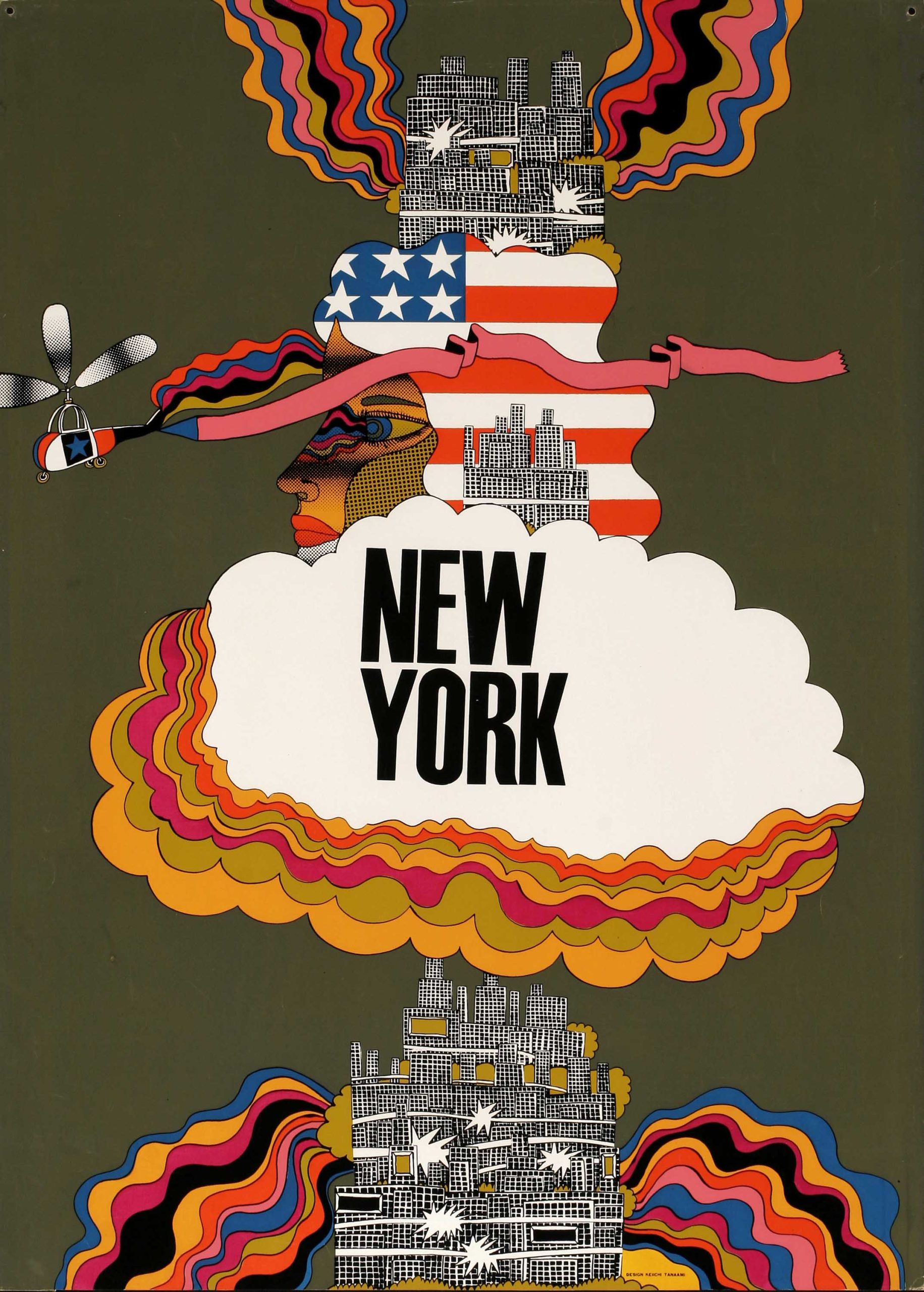

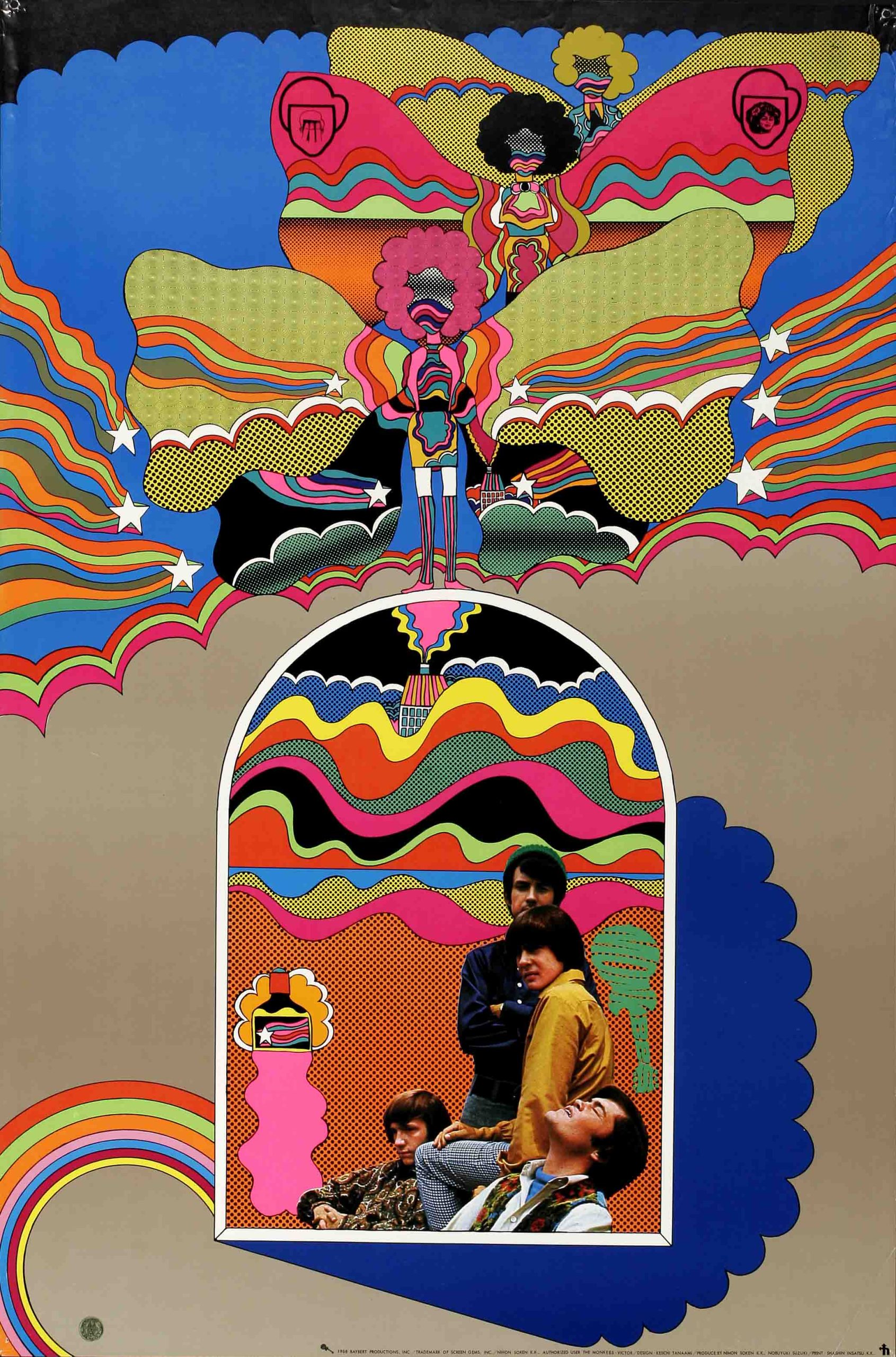

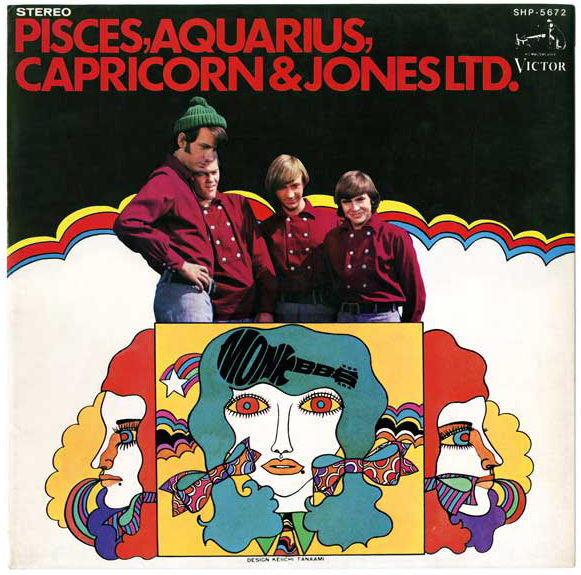

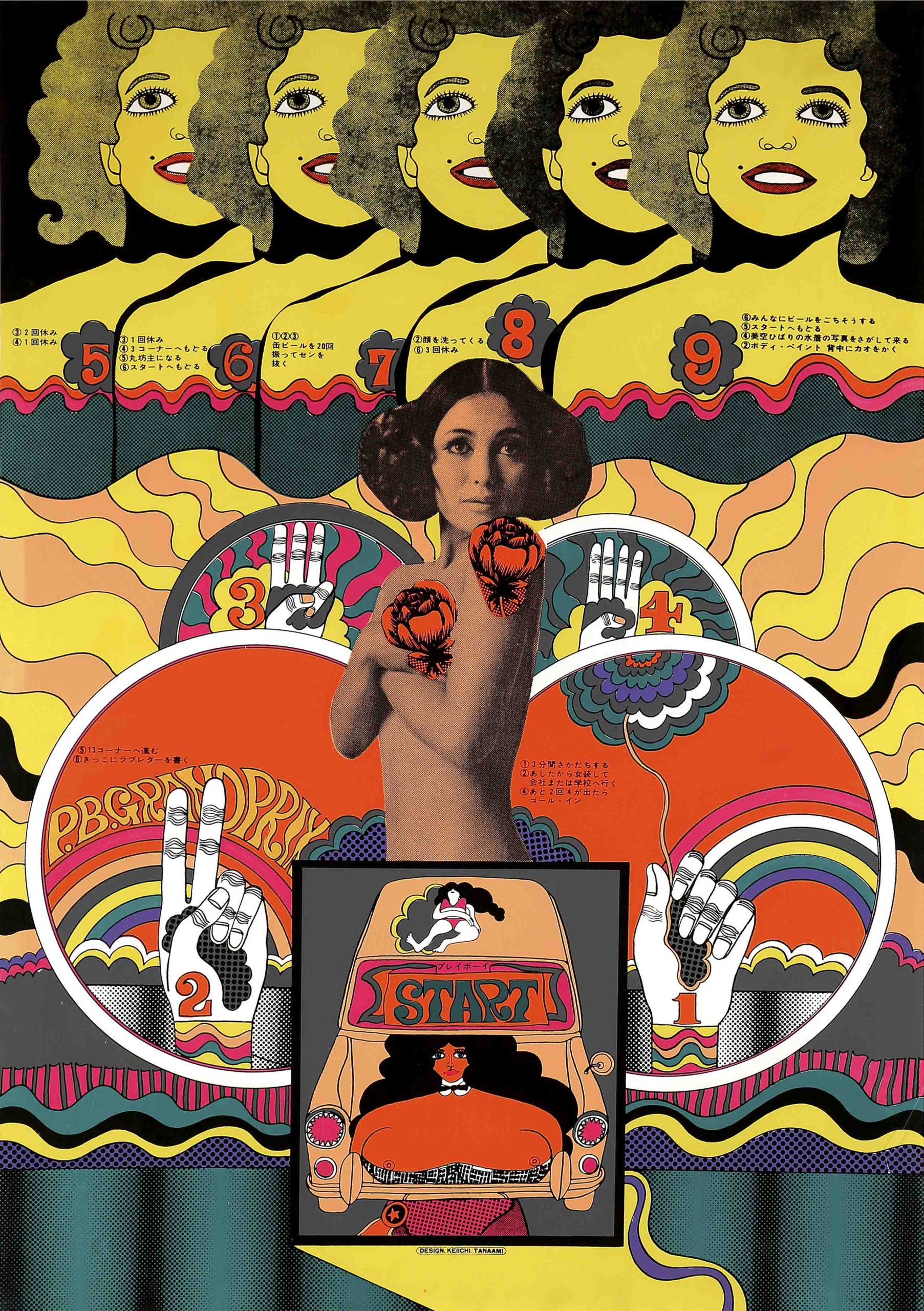

Made in Japan: 20th-Century Poster Art

Modern Japan & Poster Design

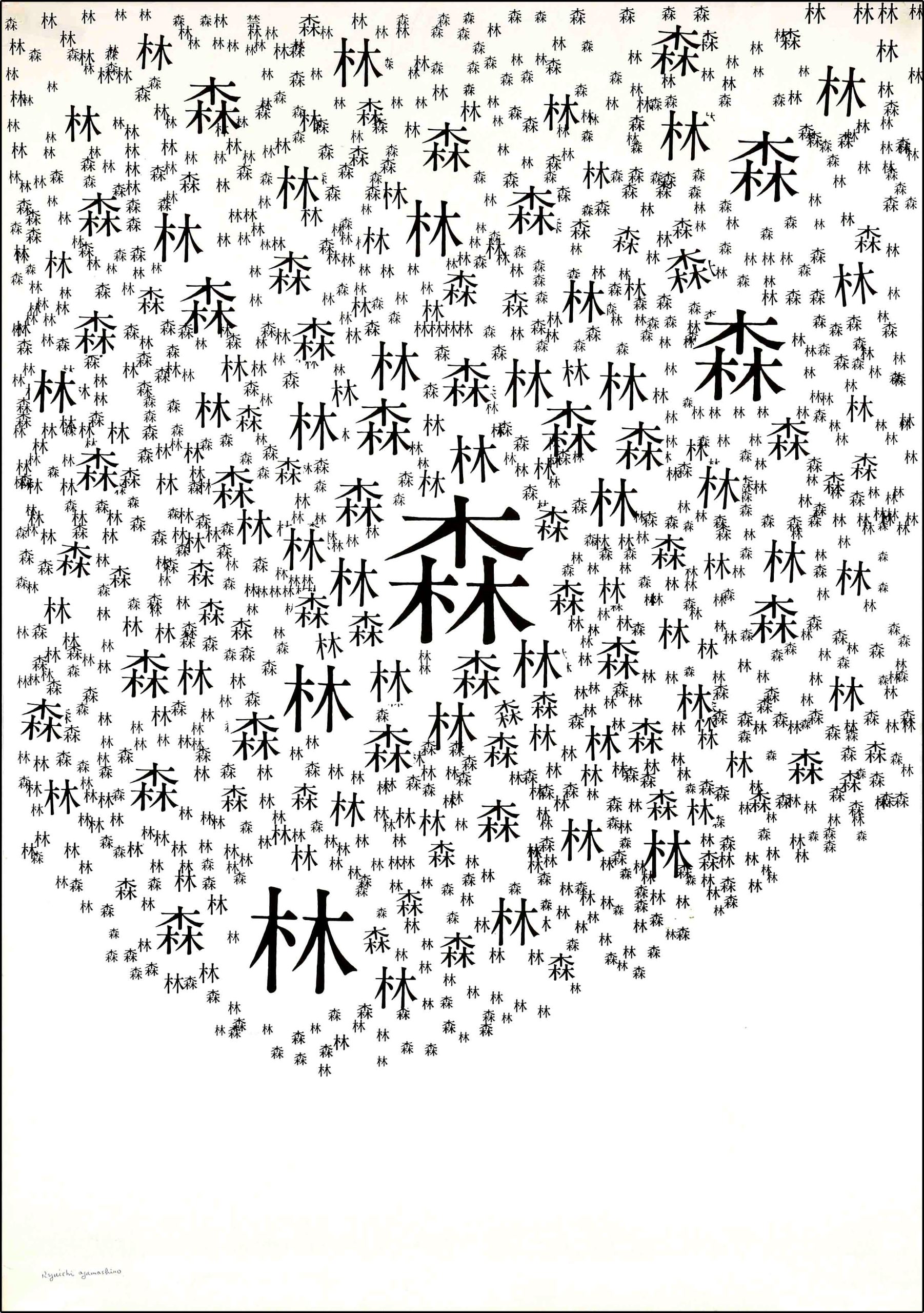

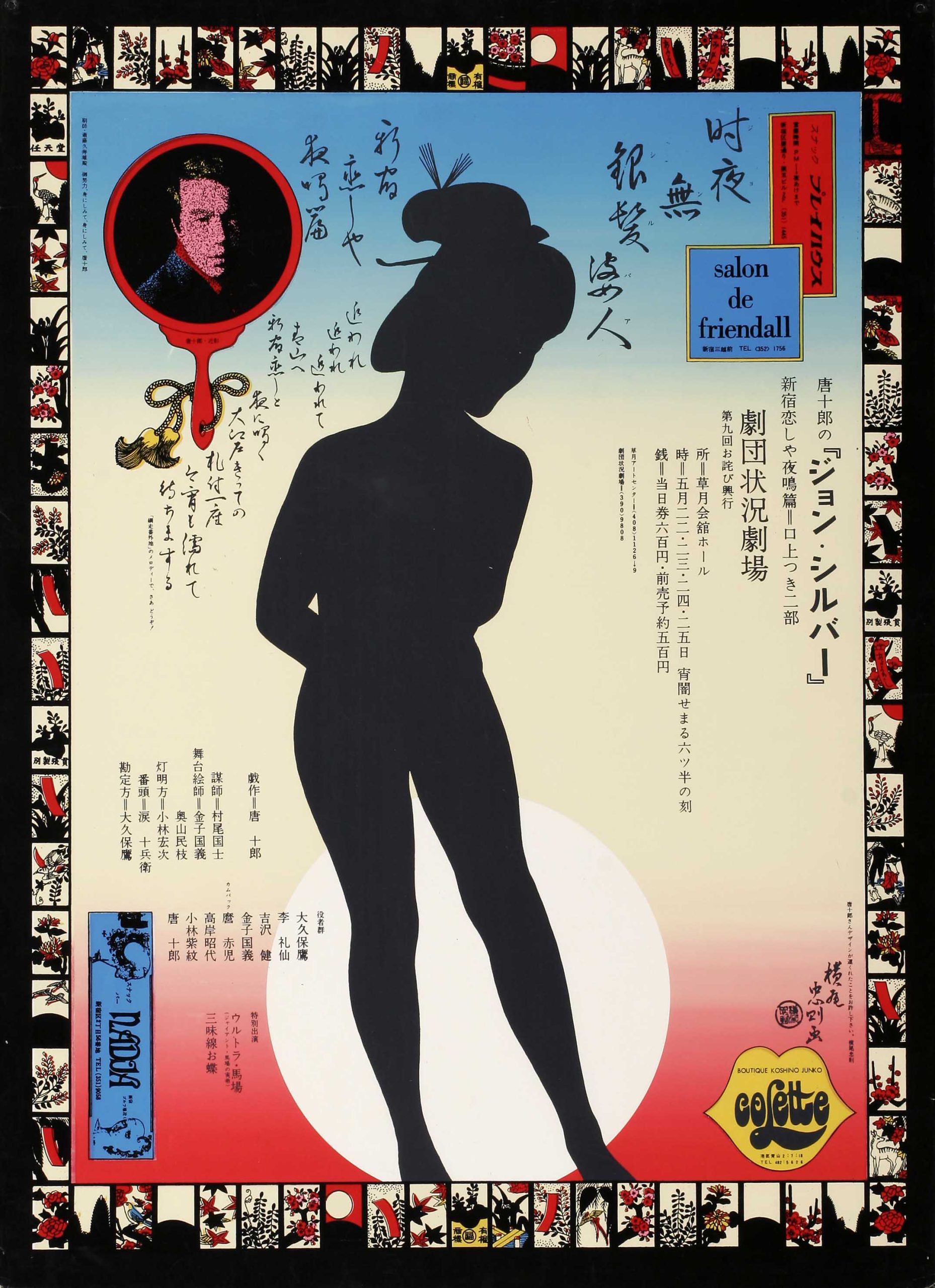

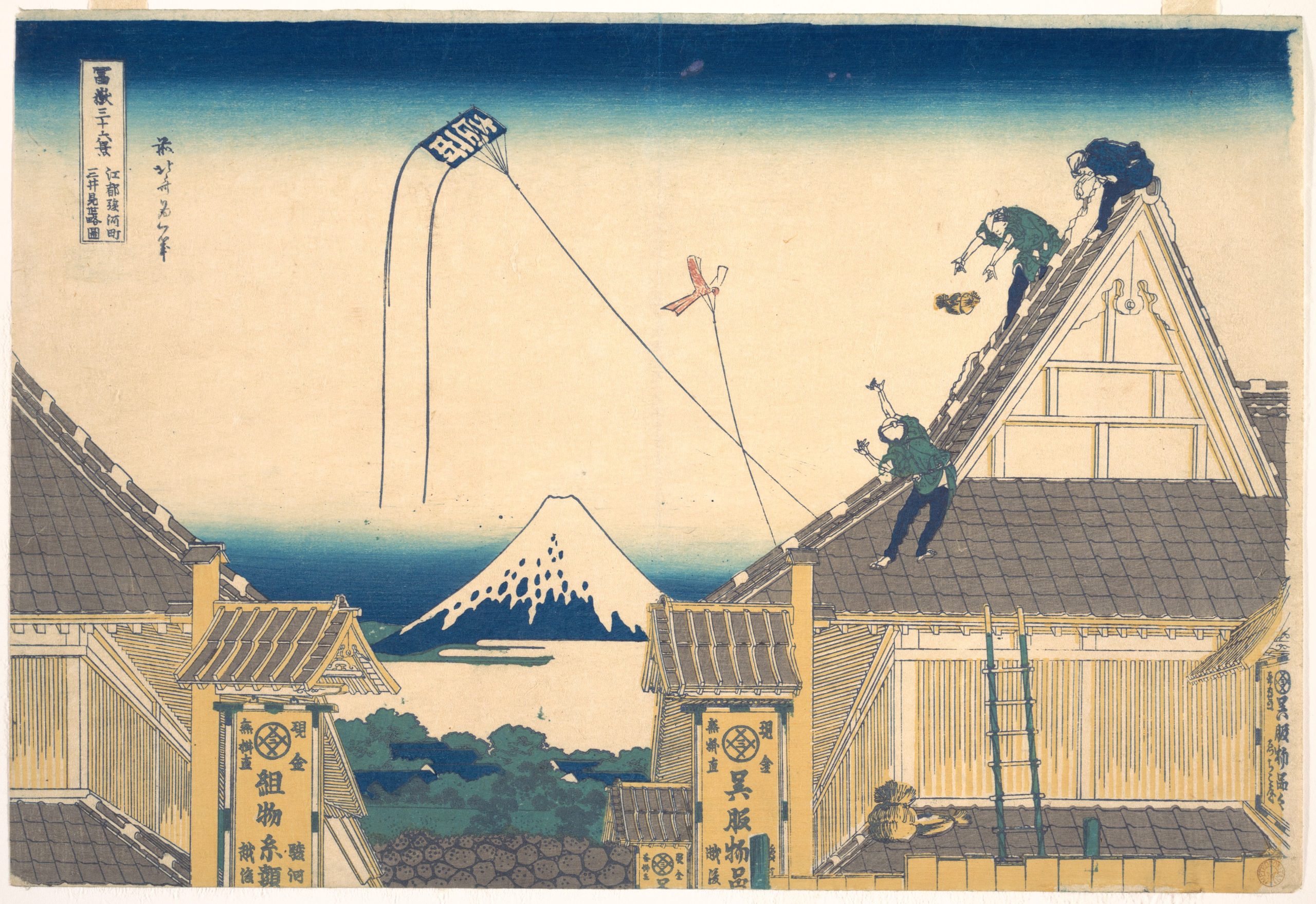

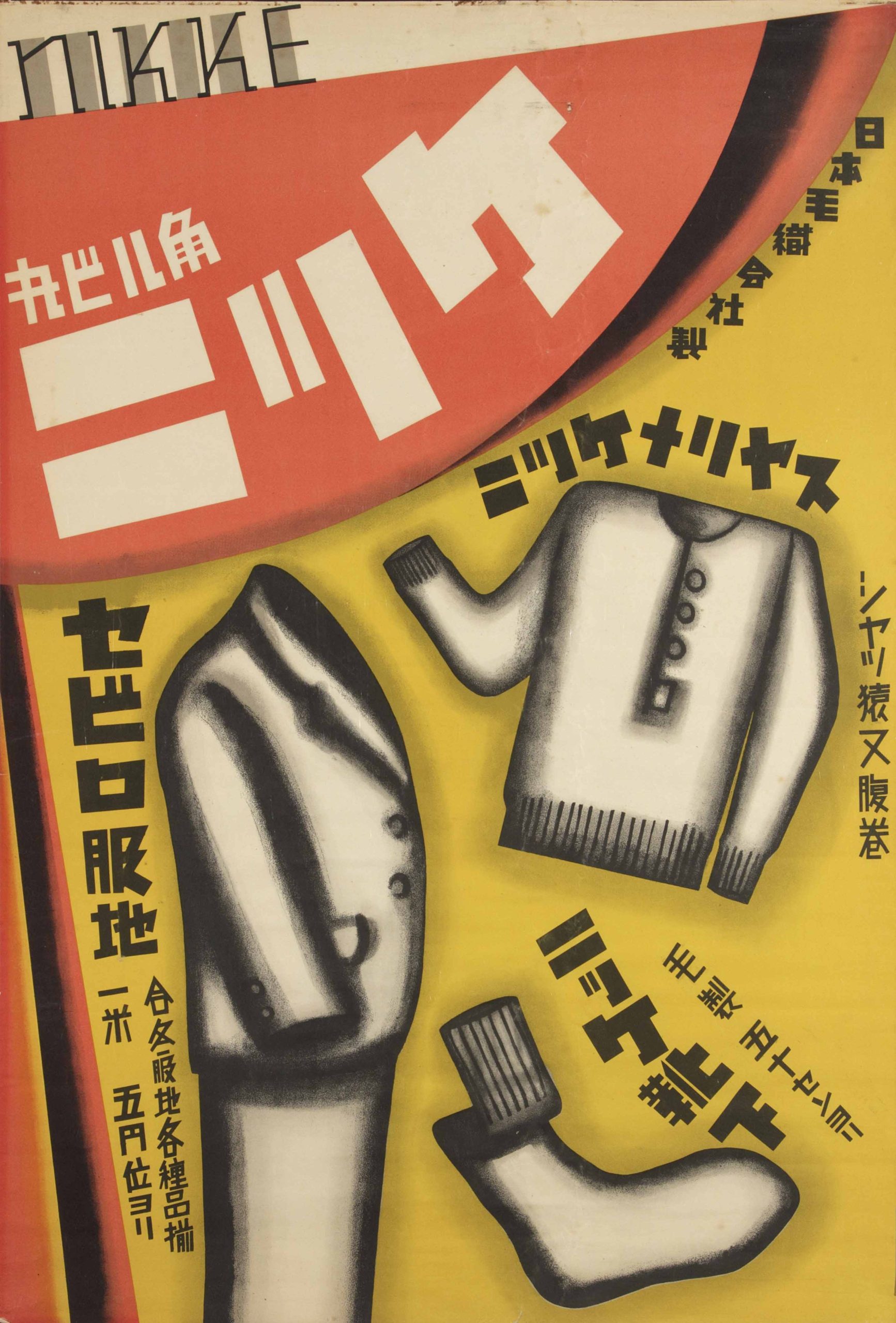

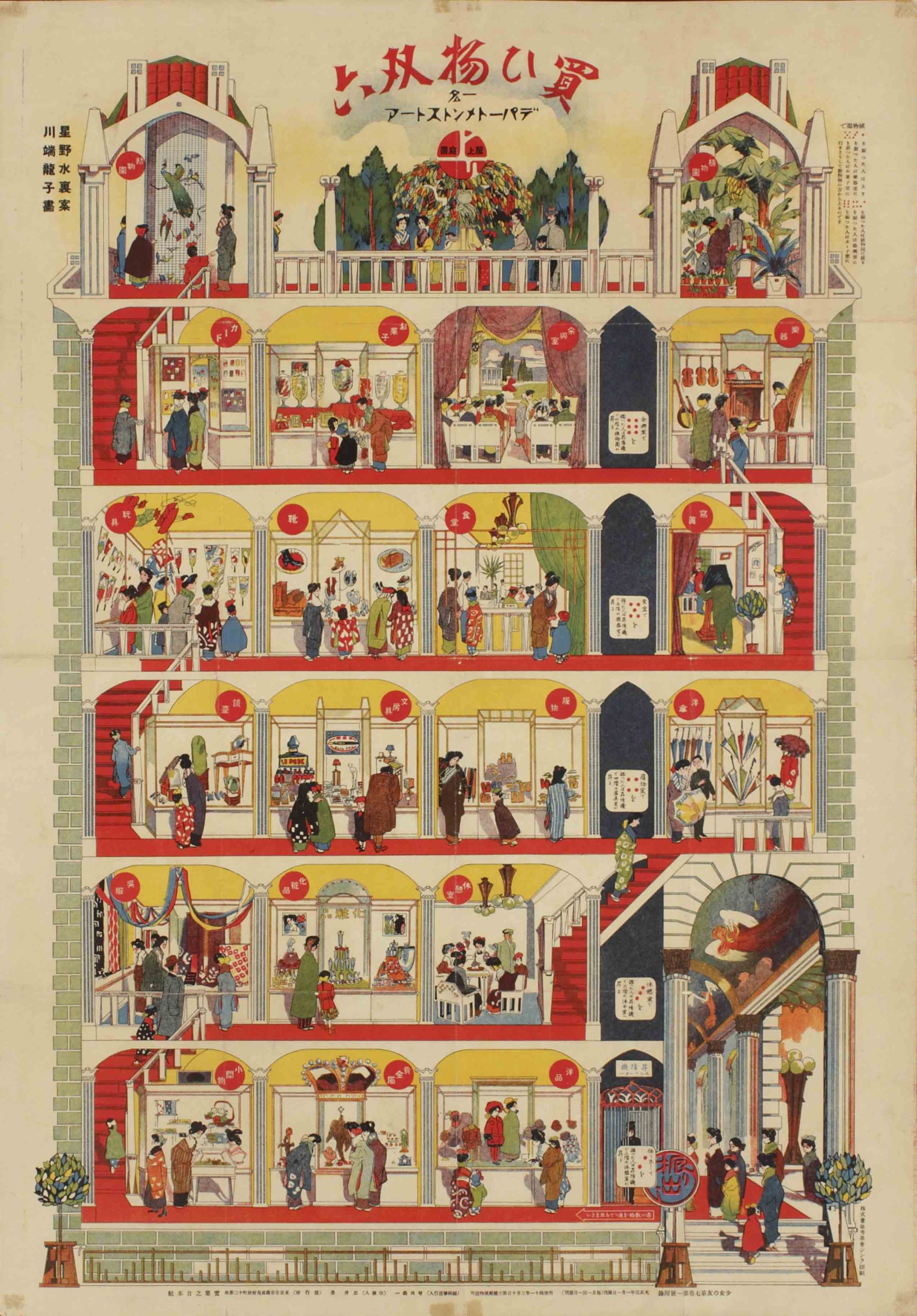

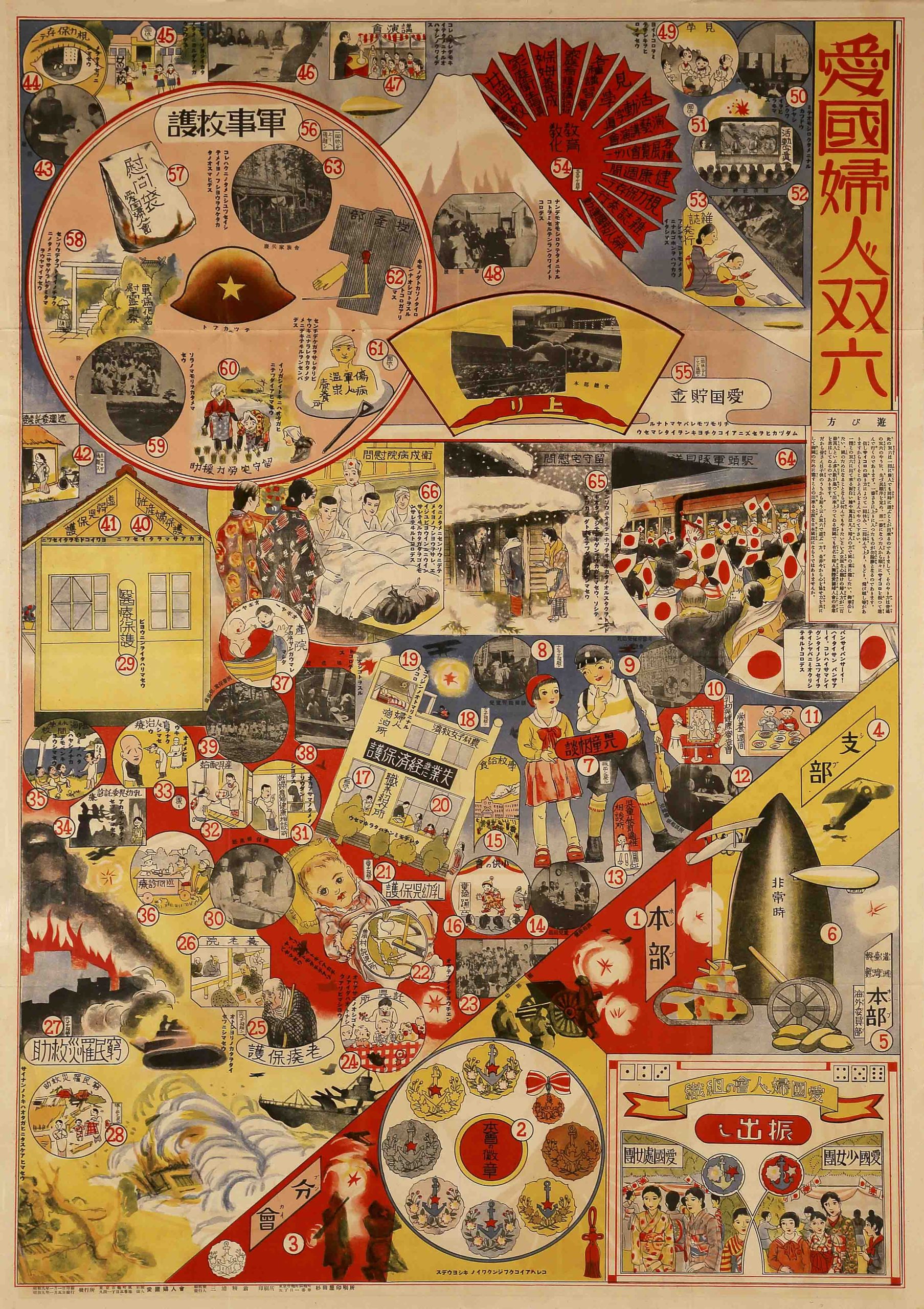

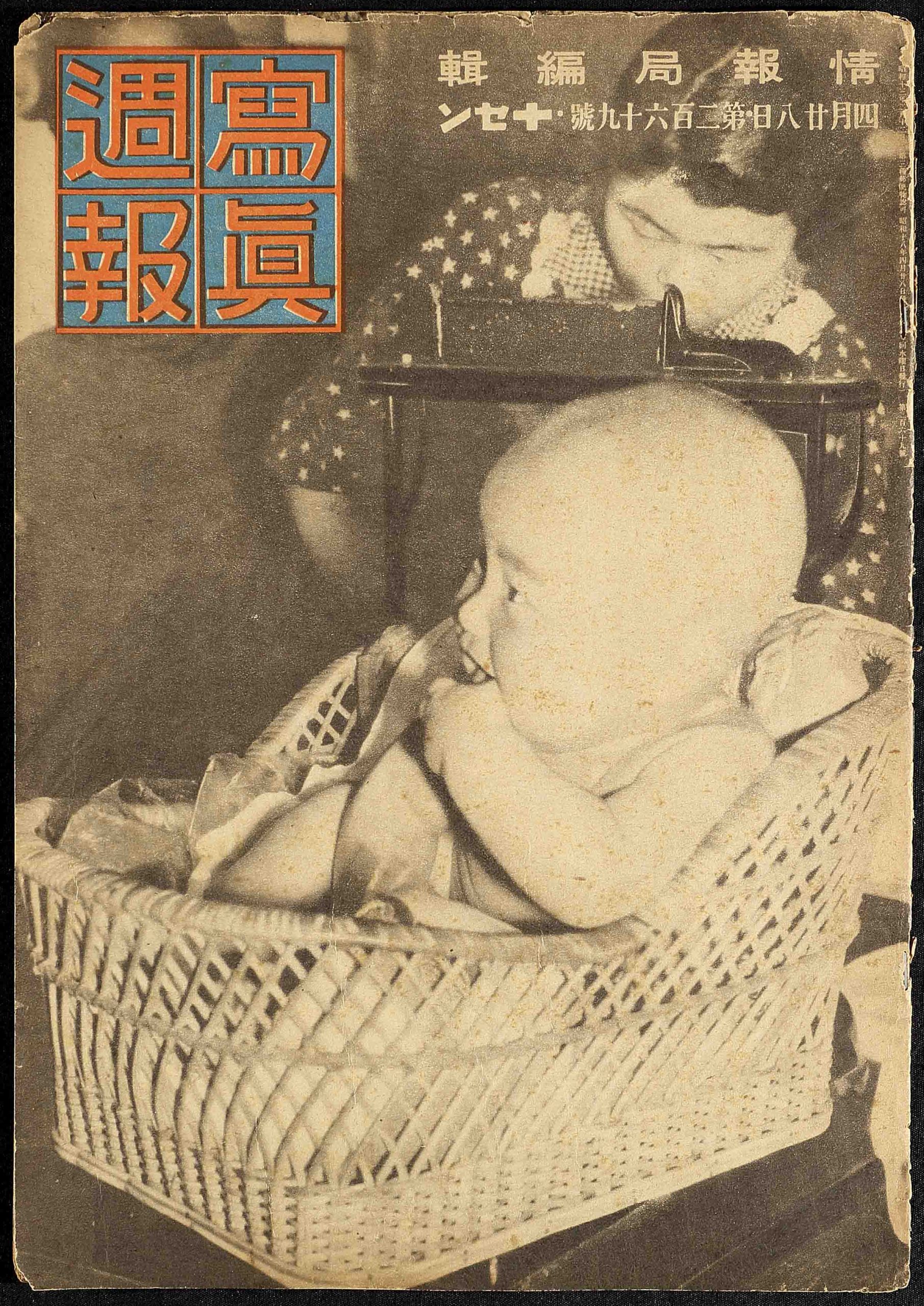

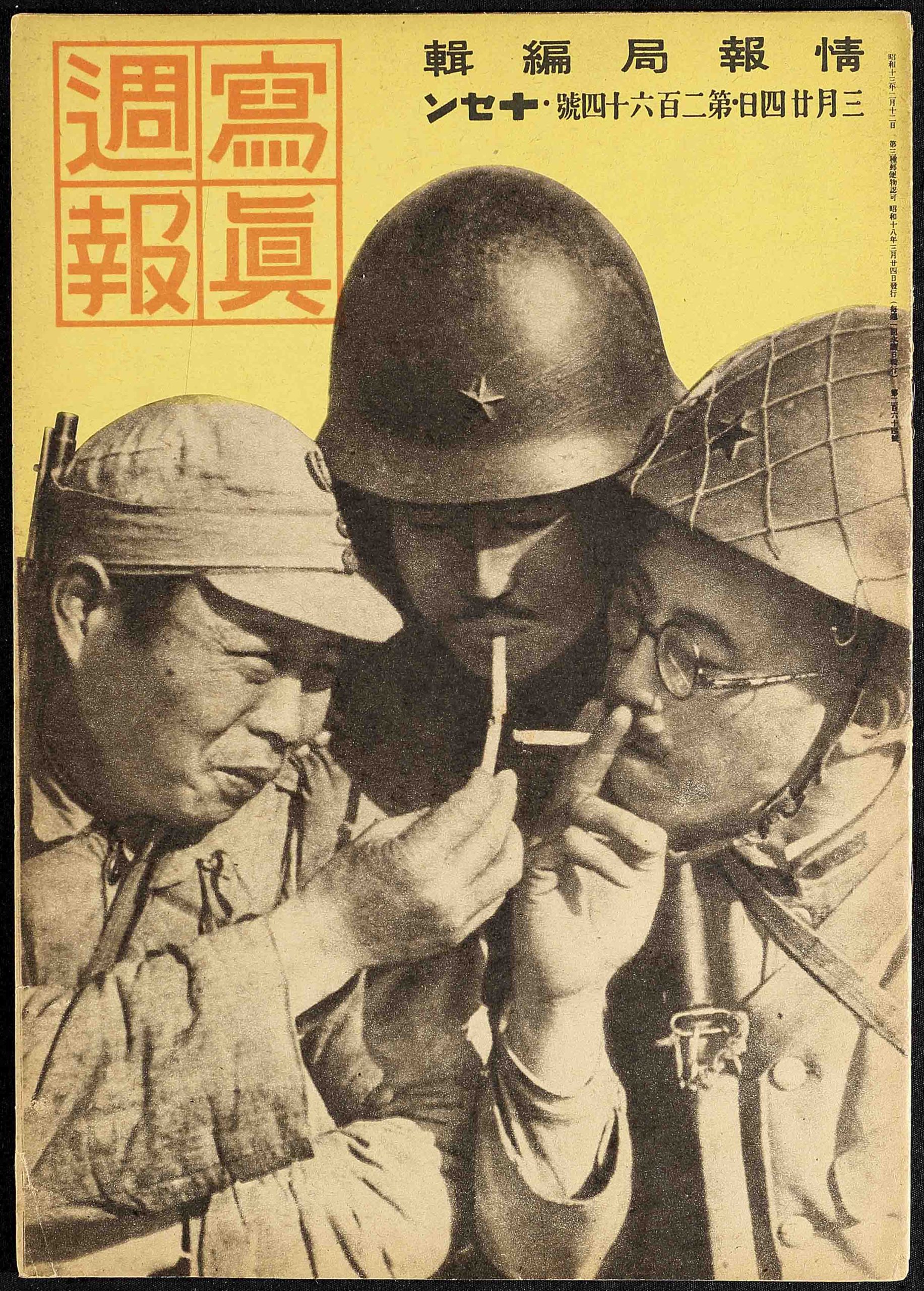

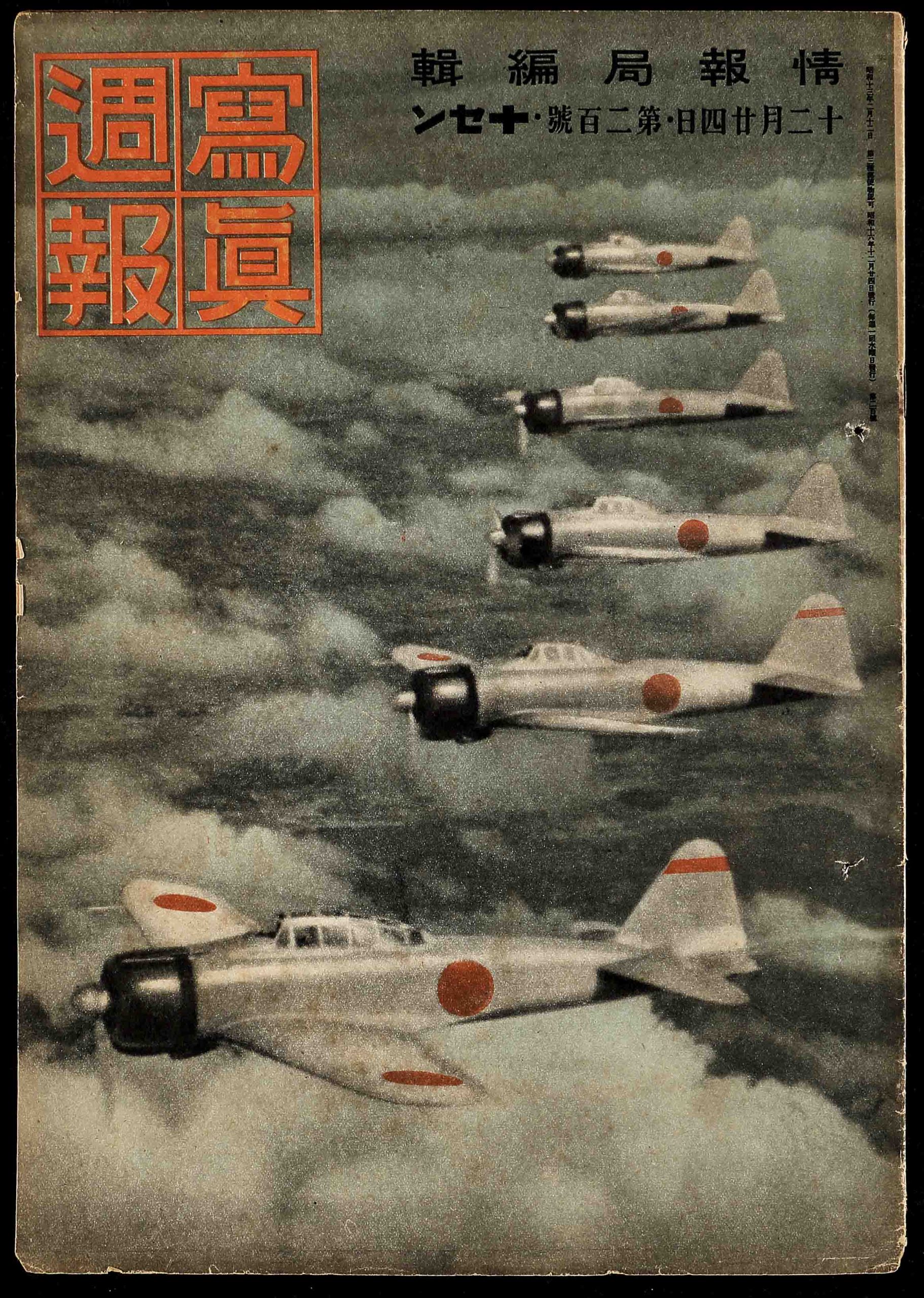

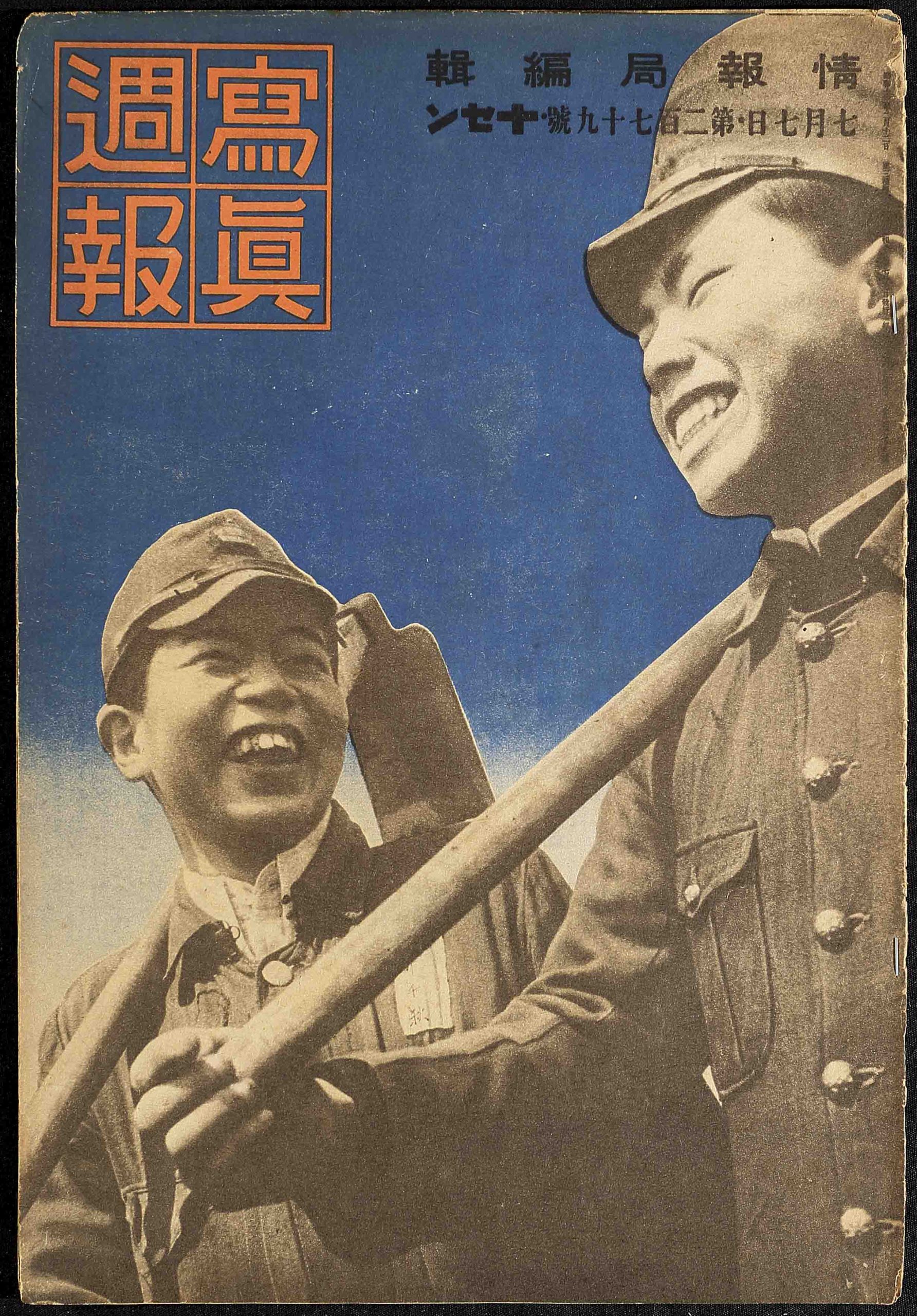

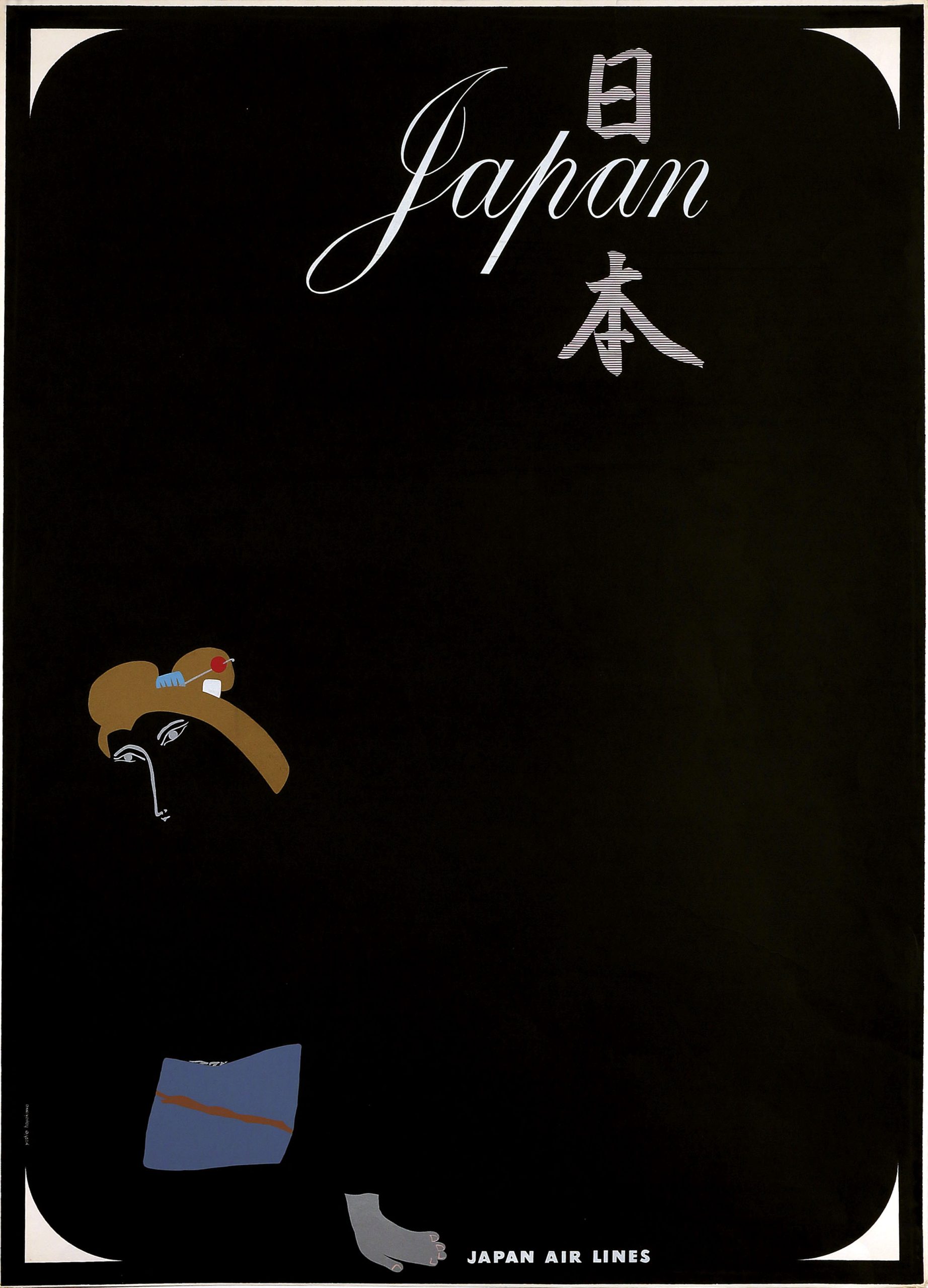

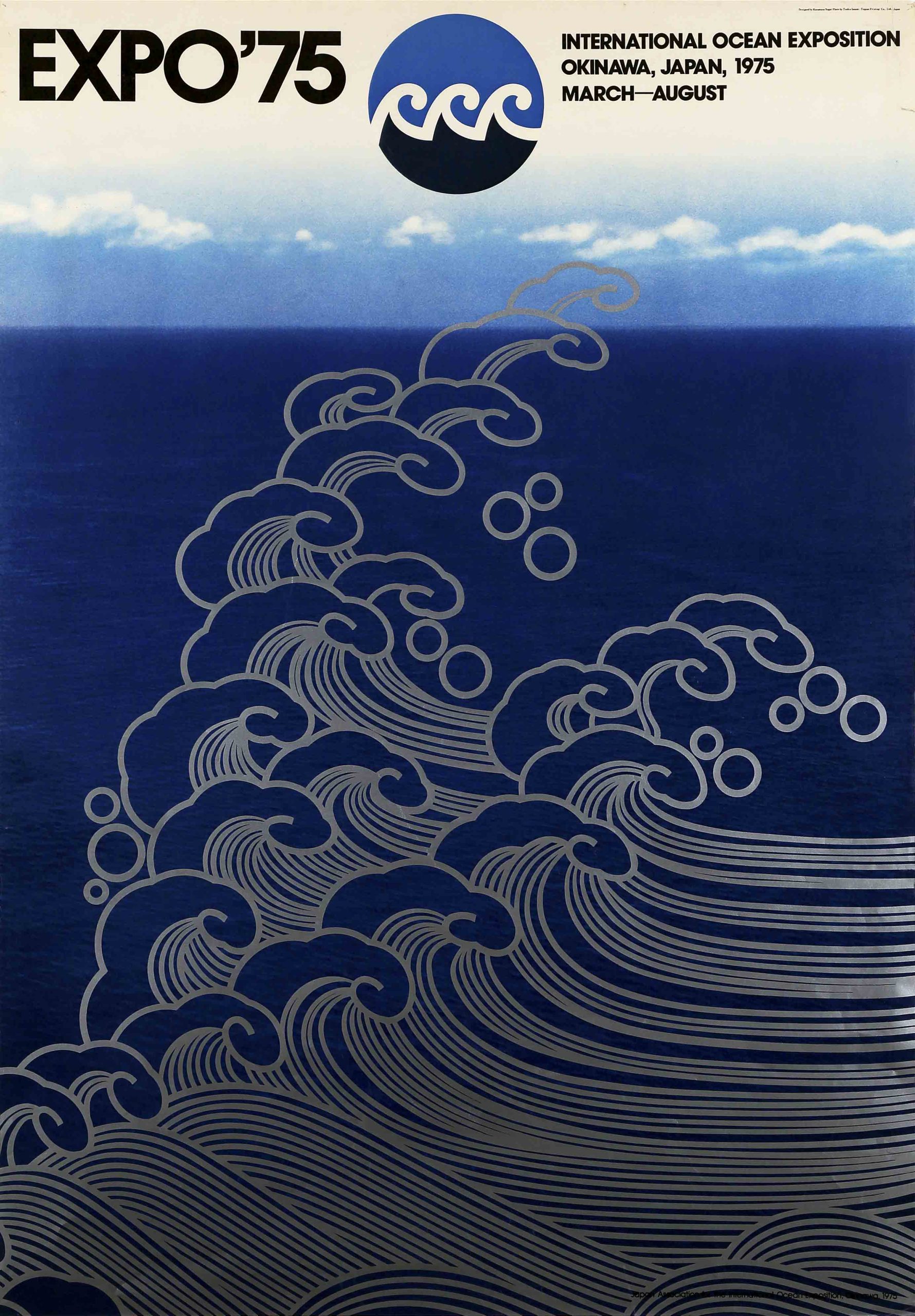

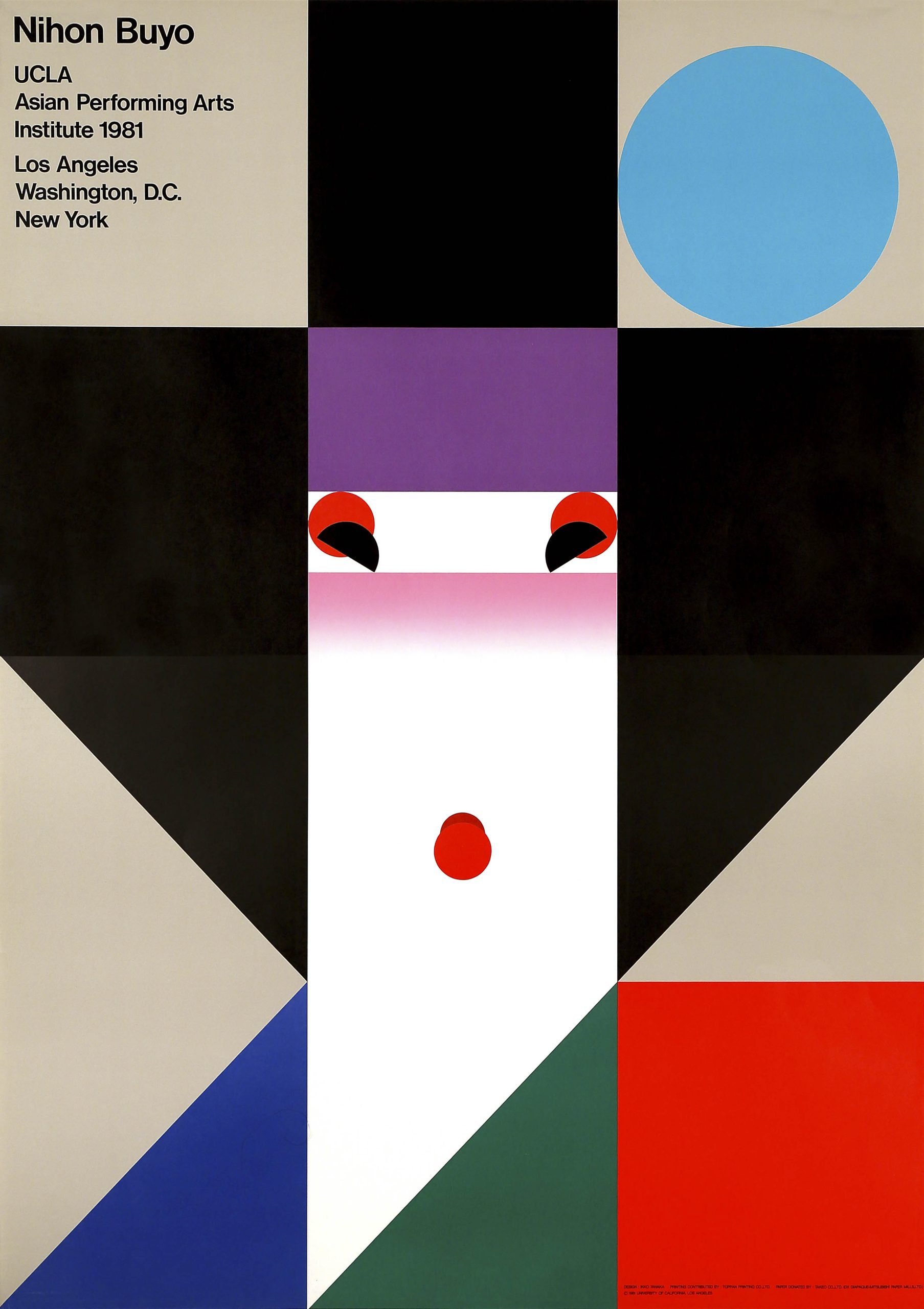

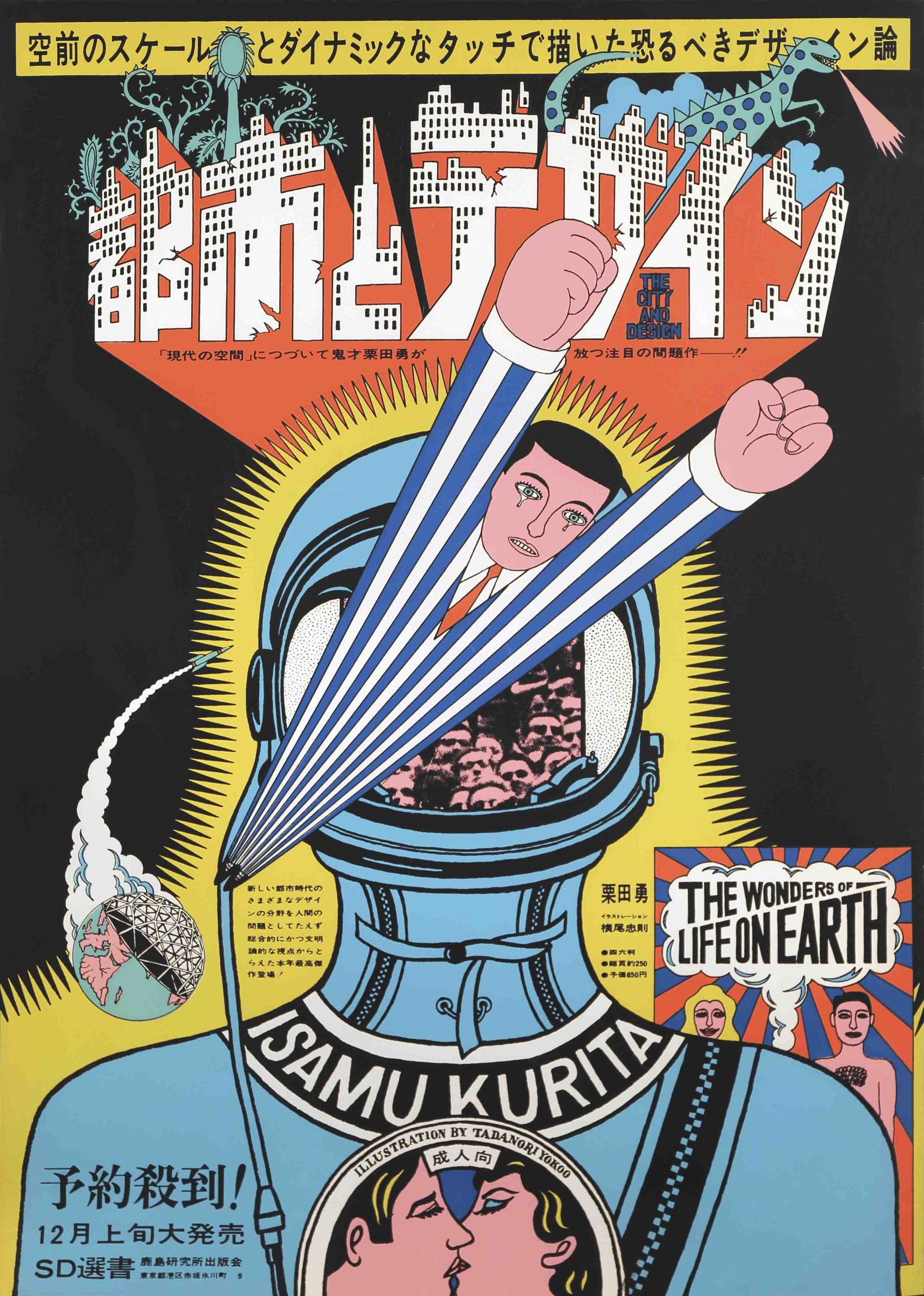

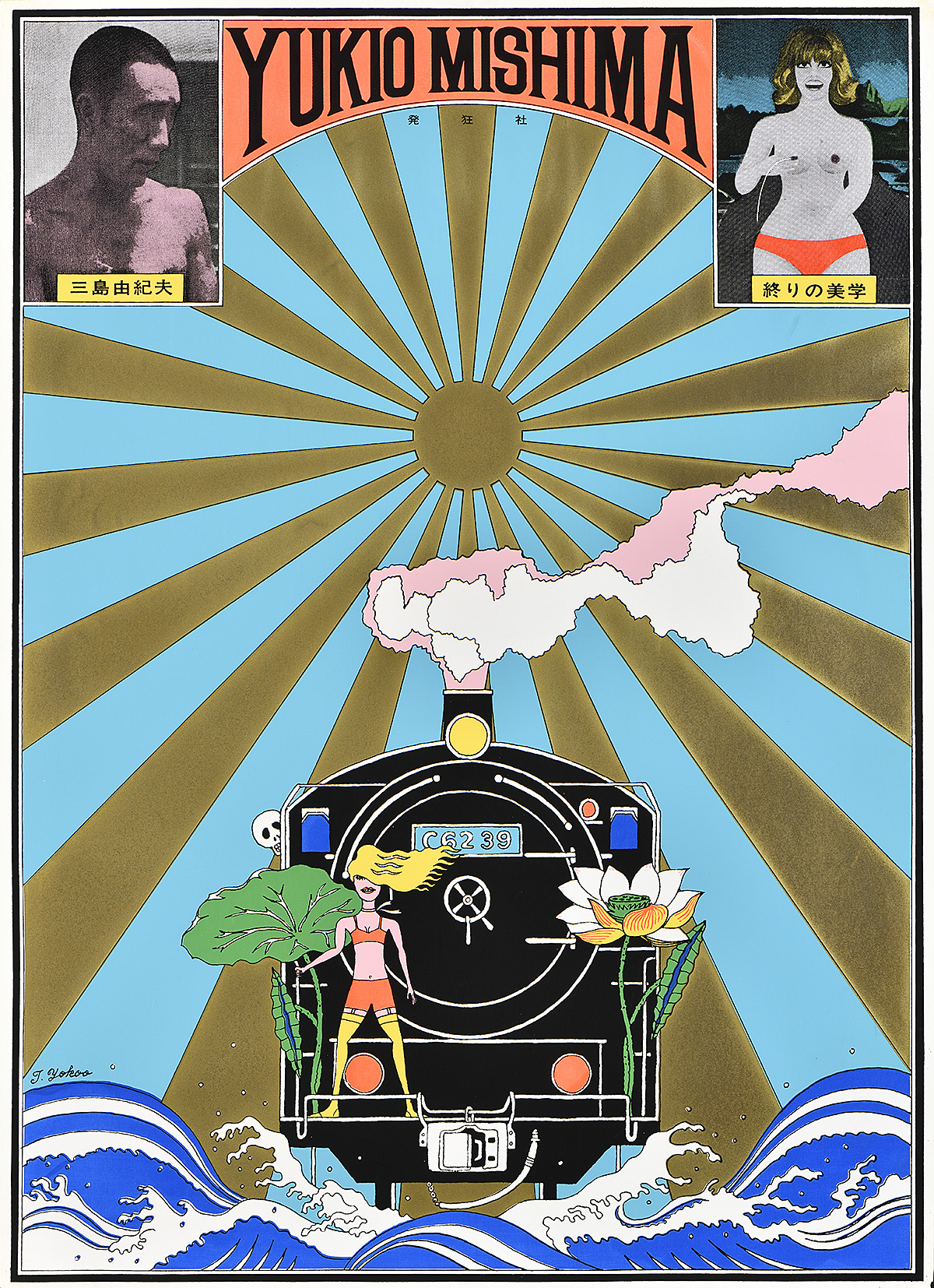

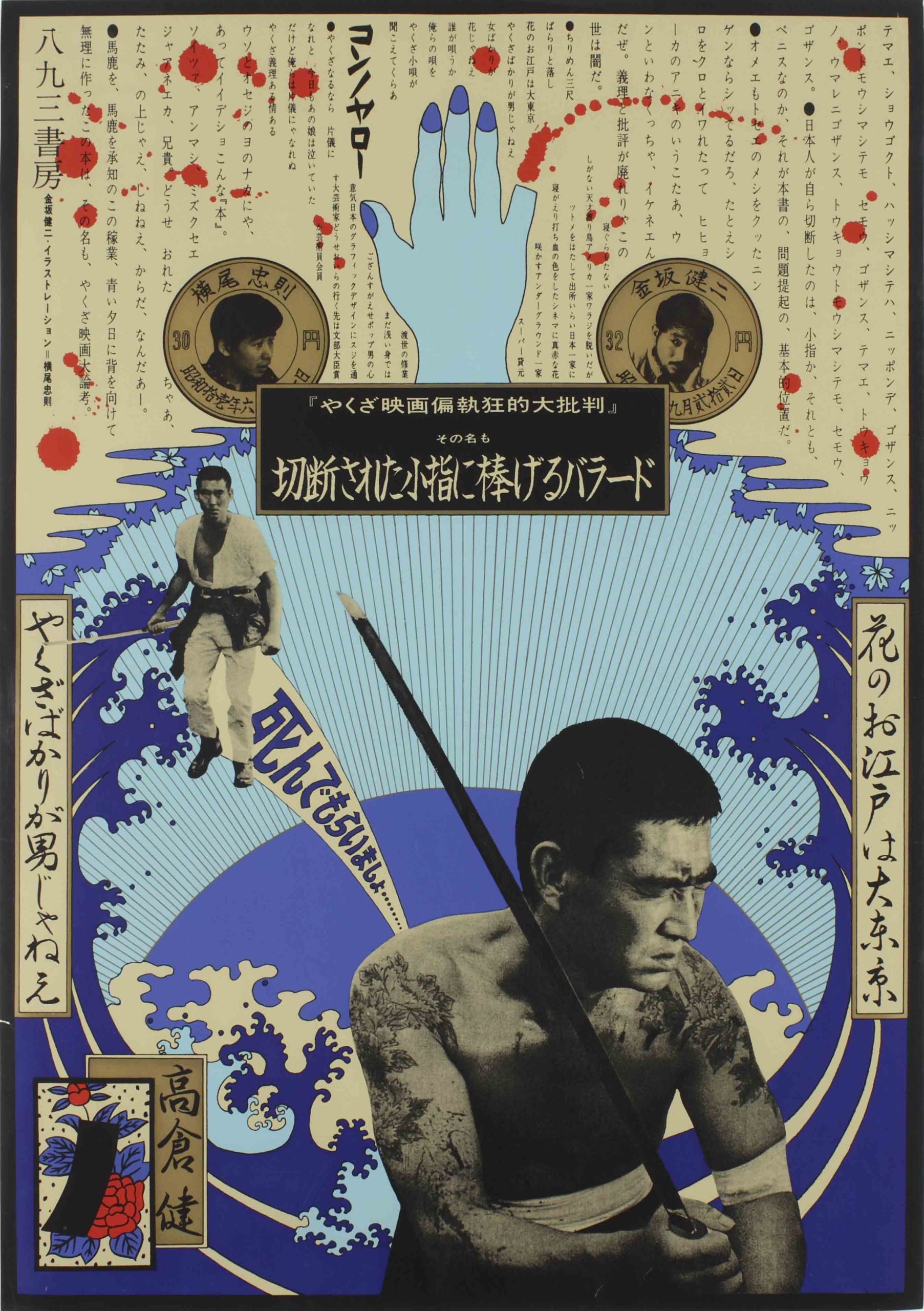

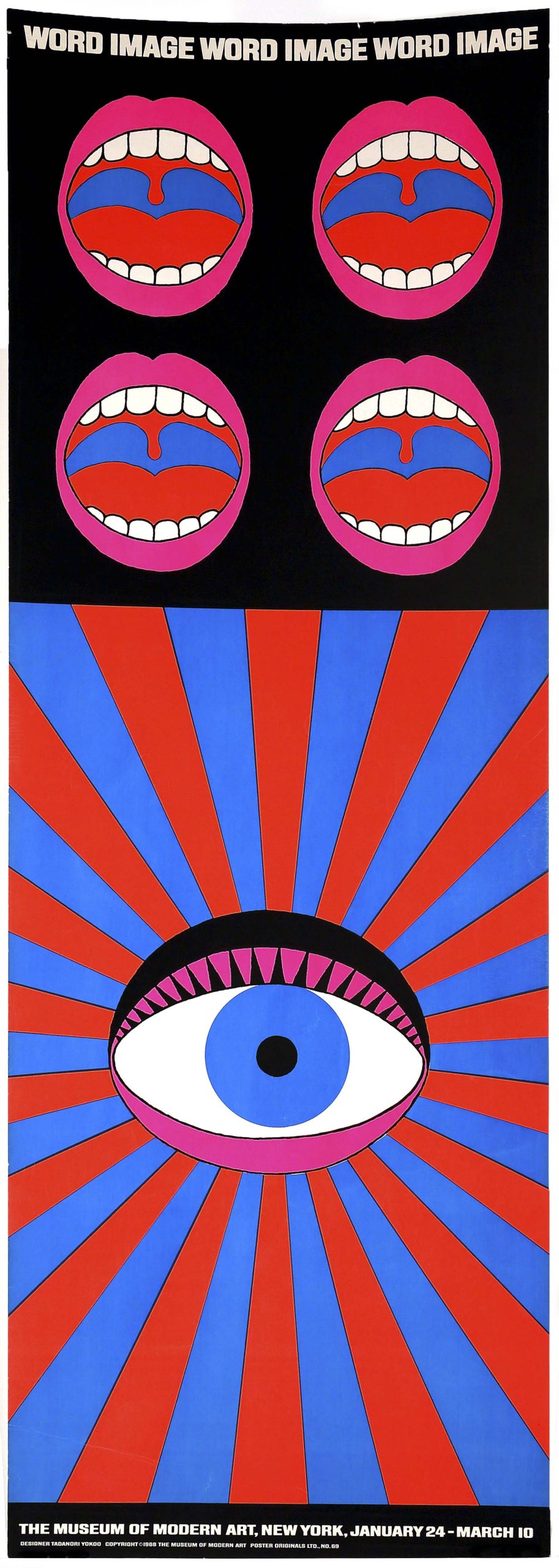

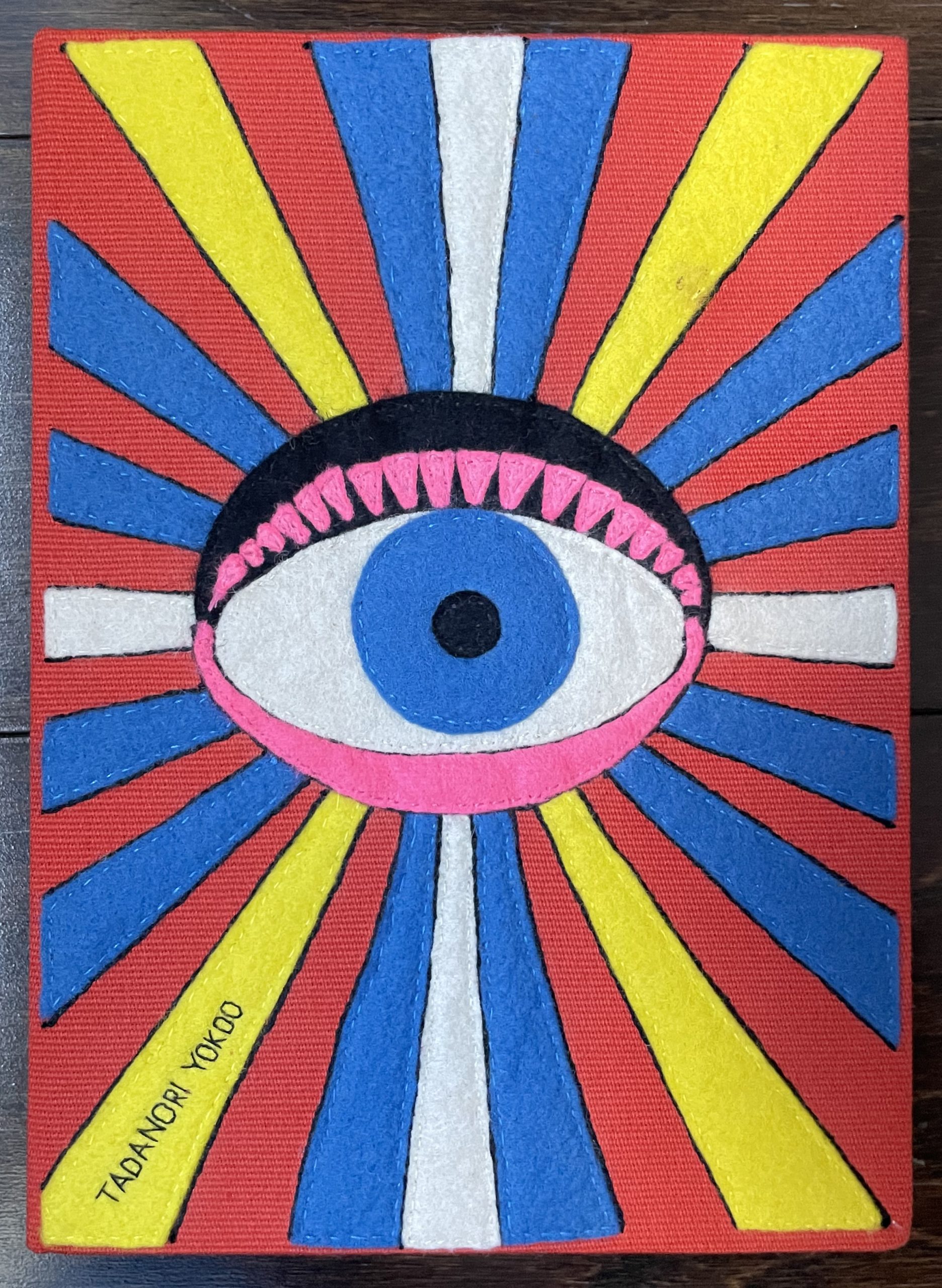

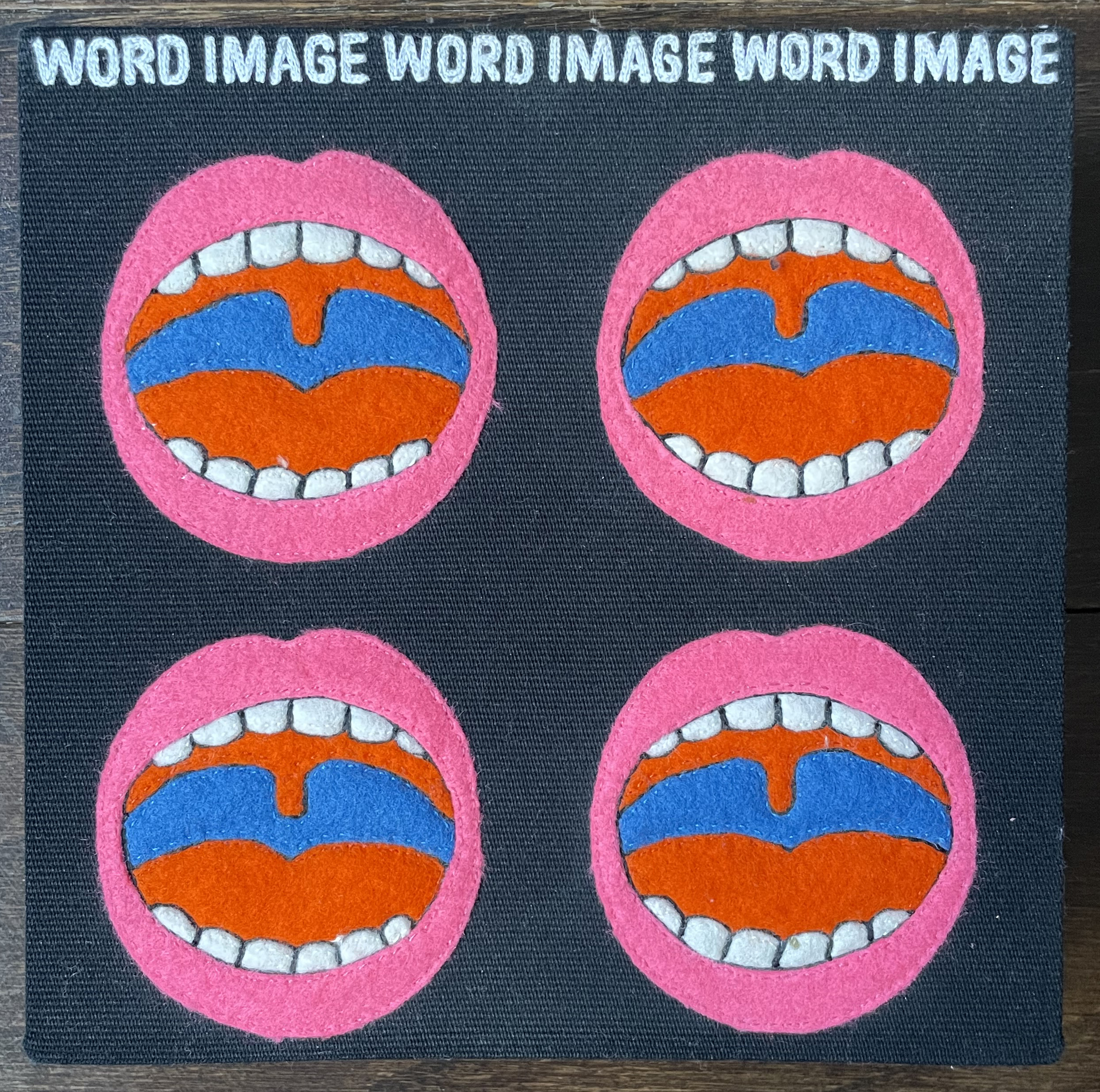

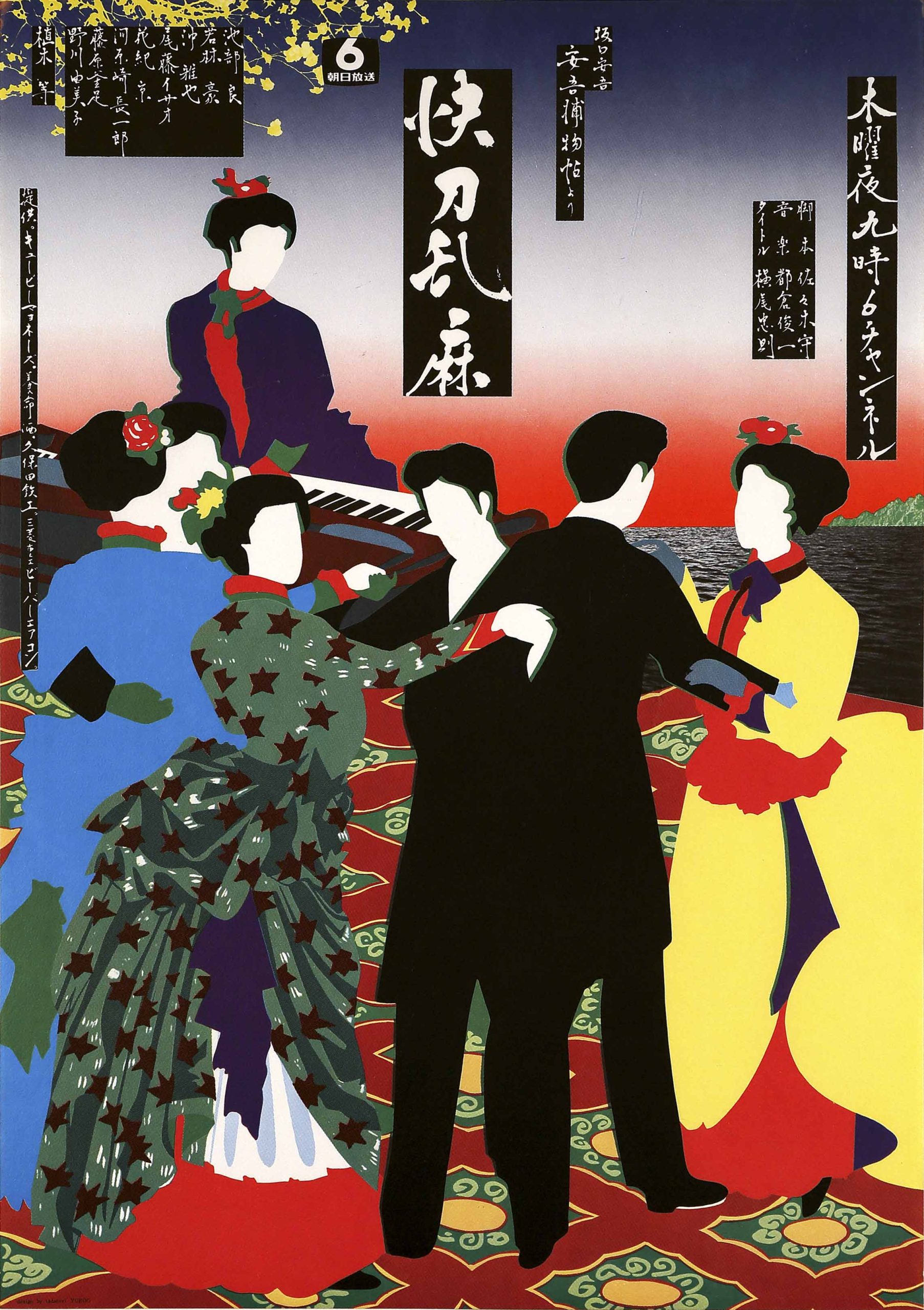

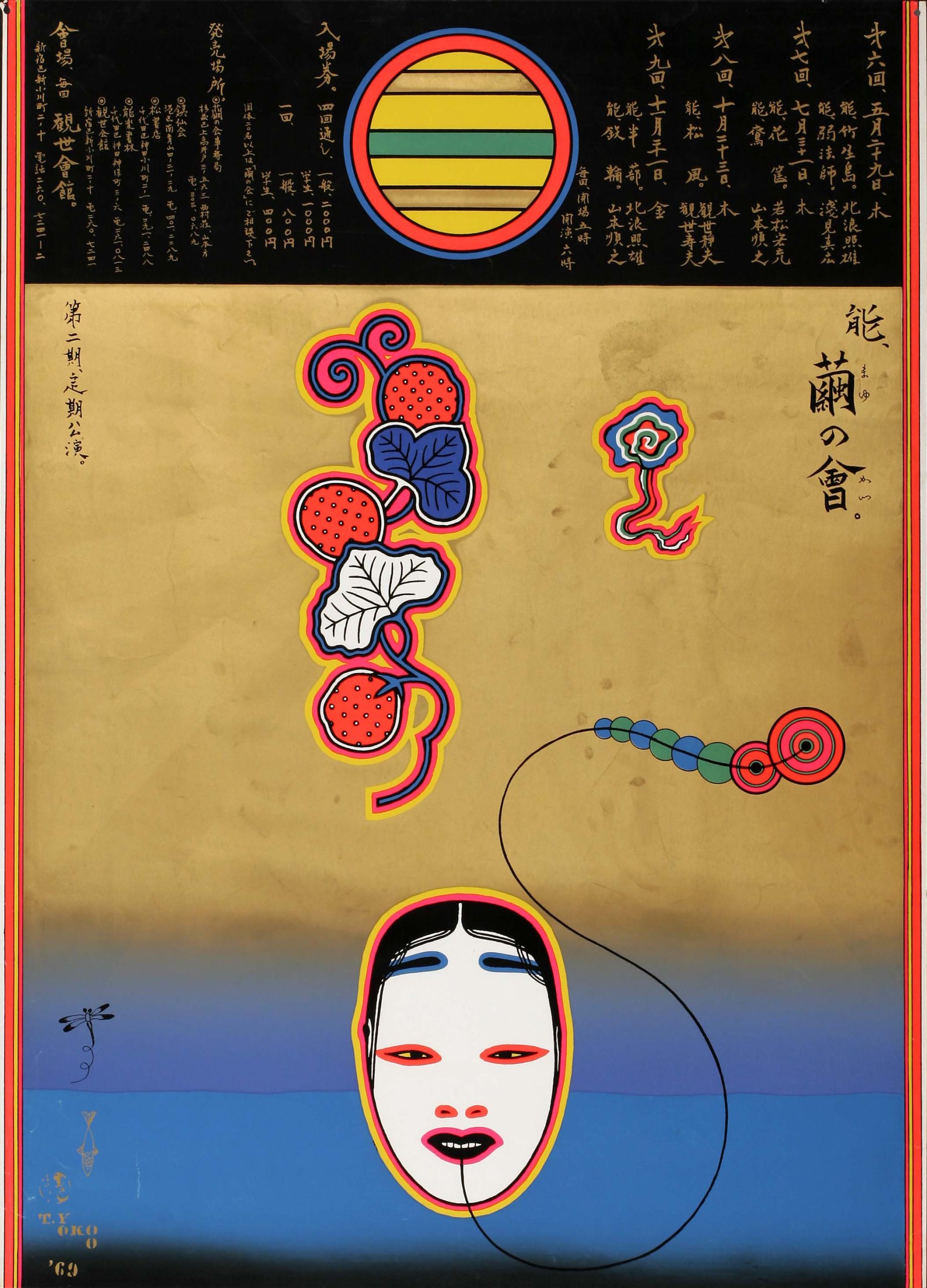

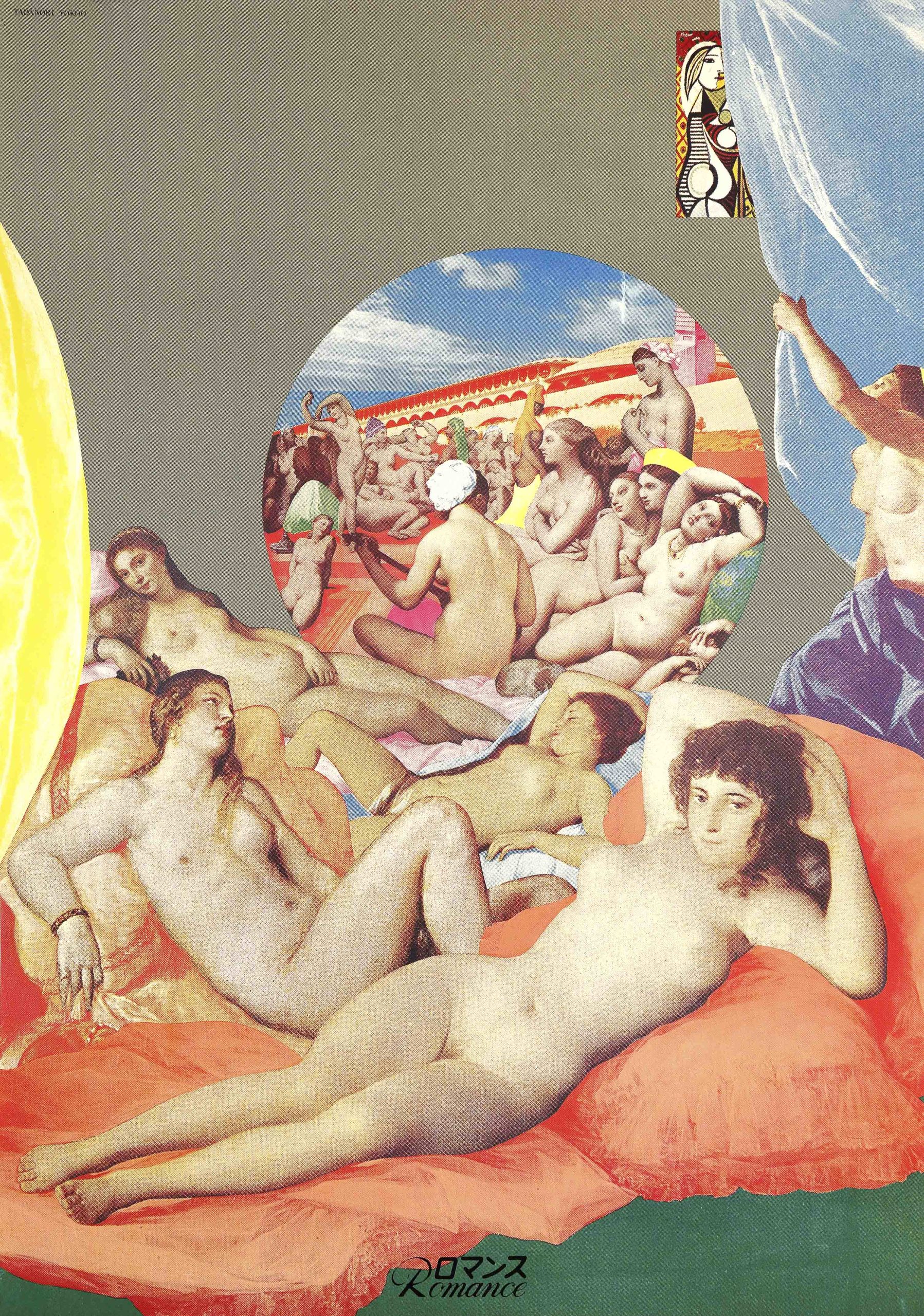

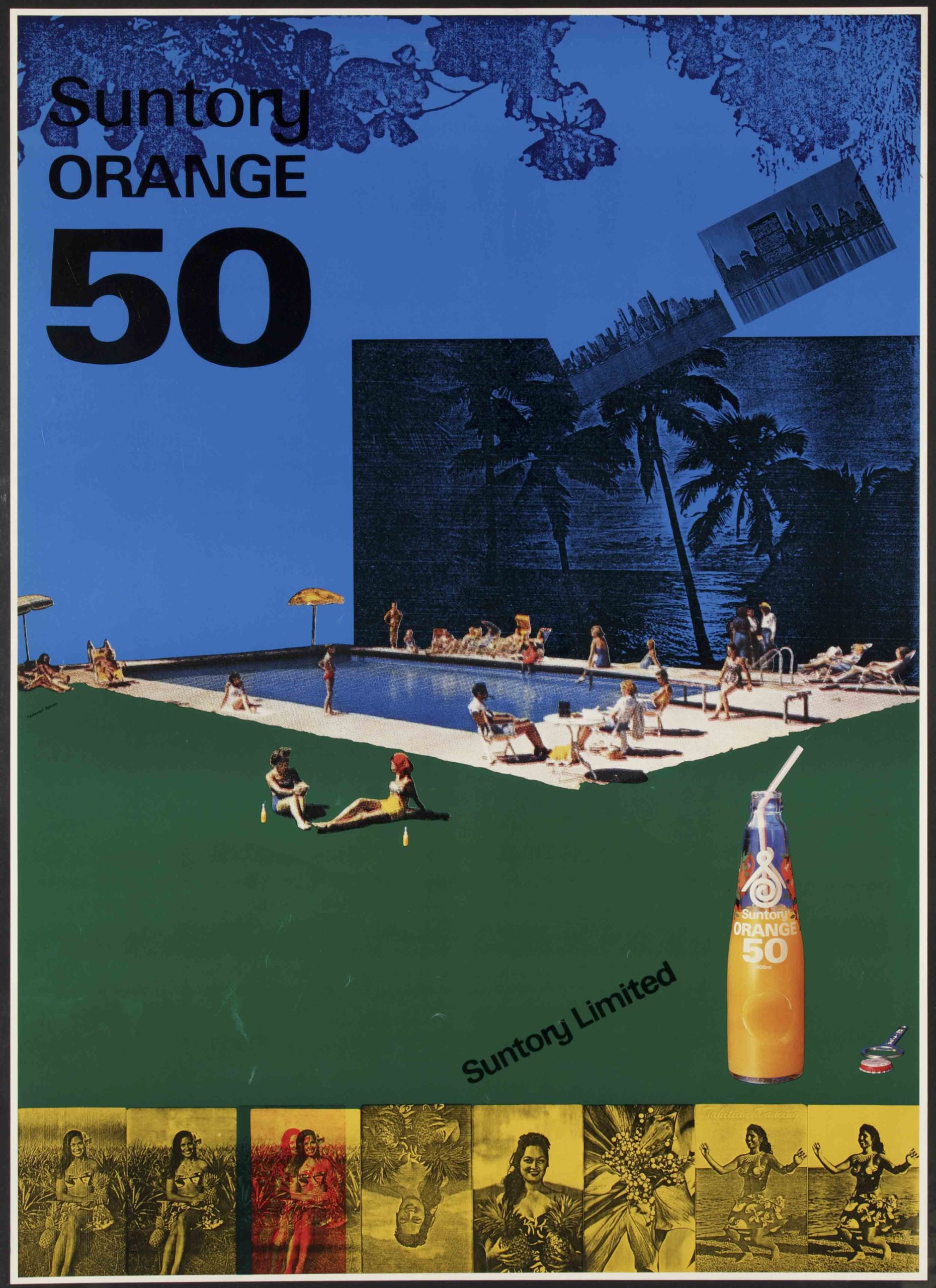

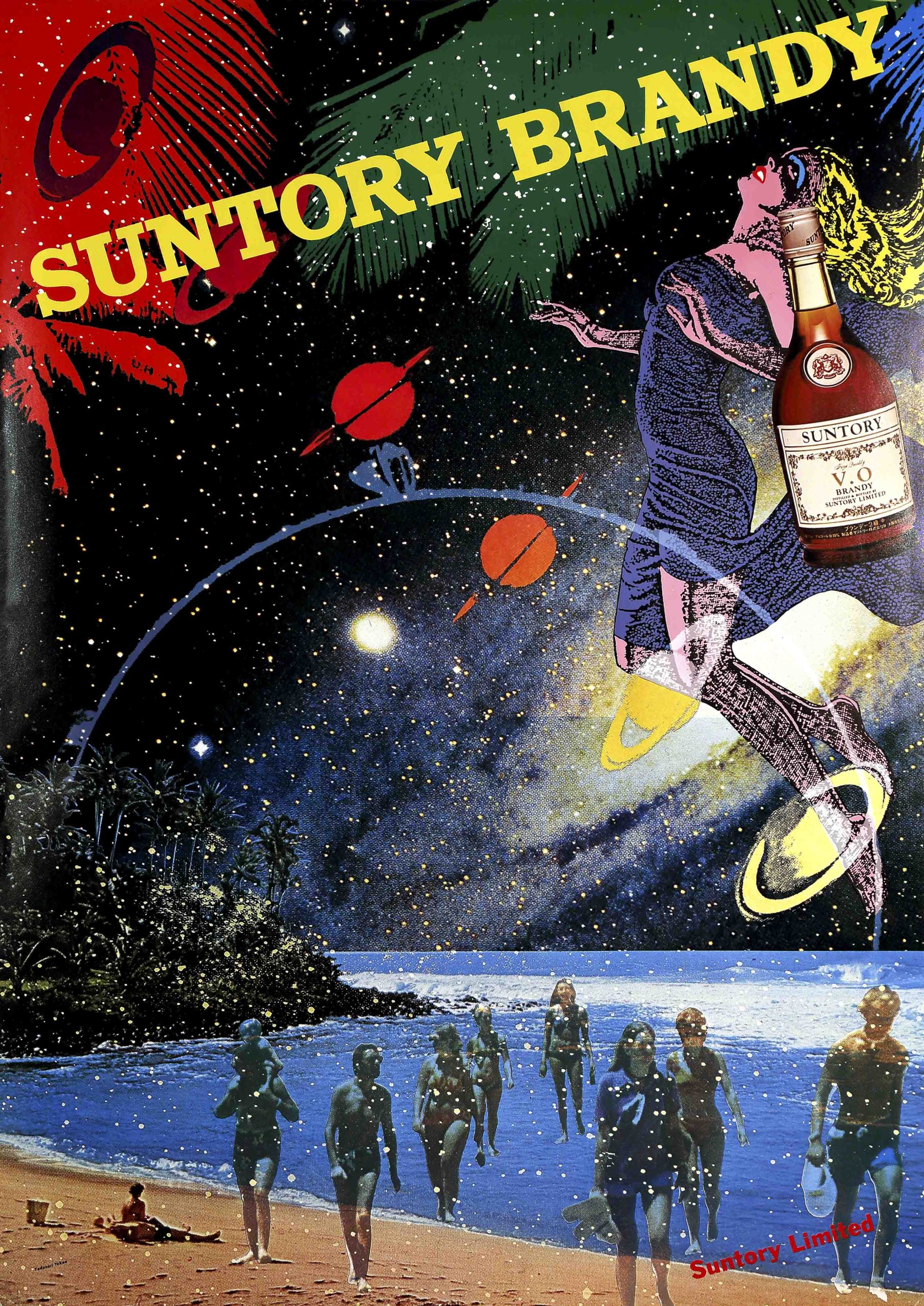

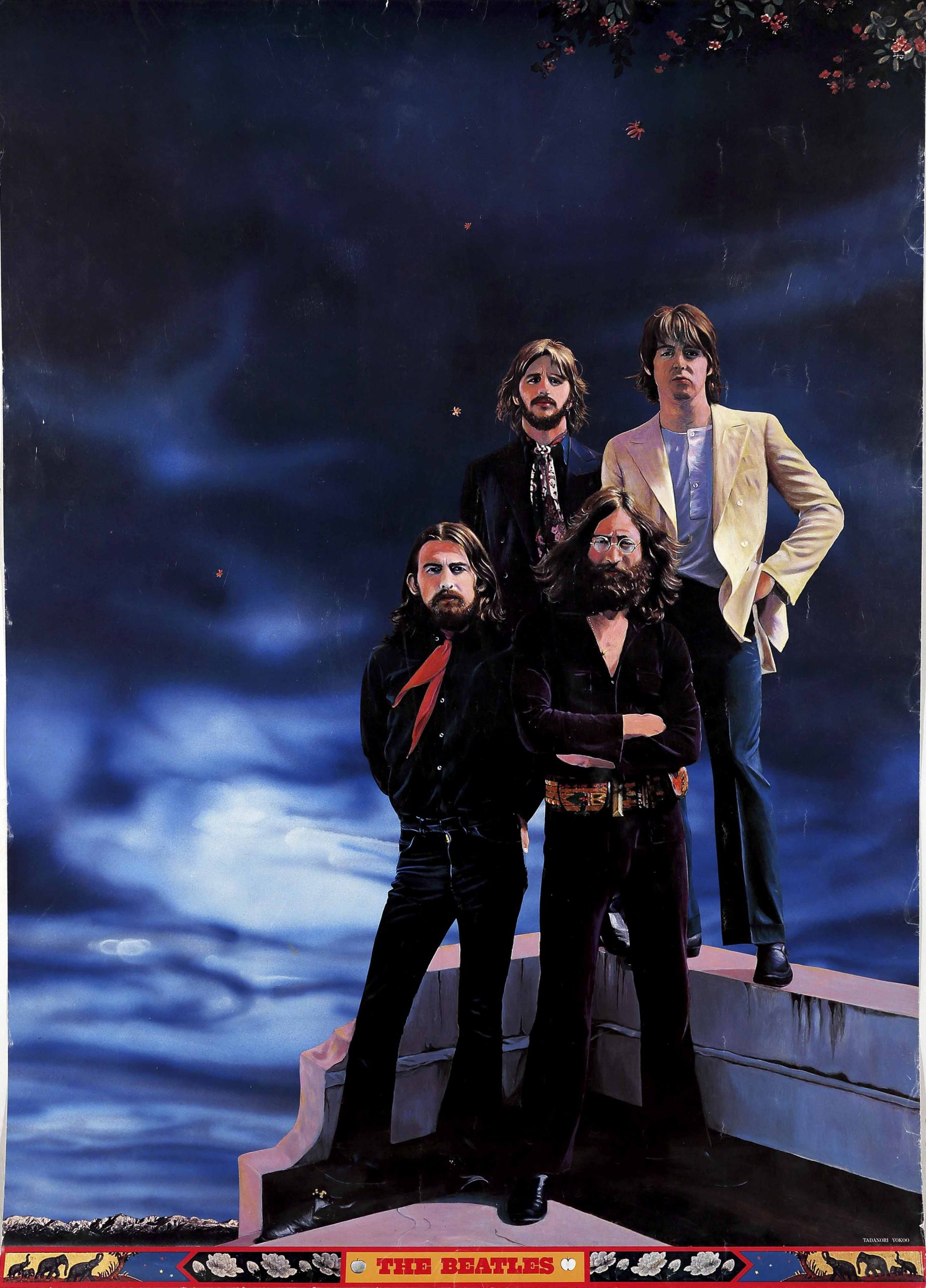

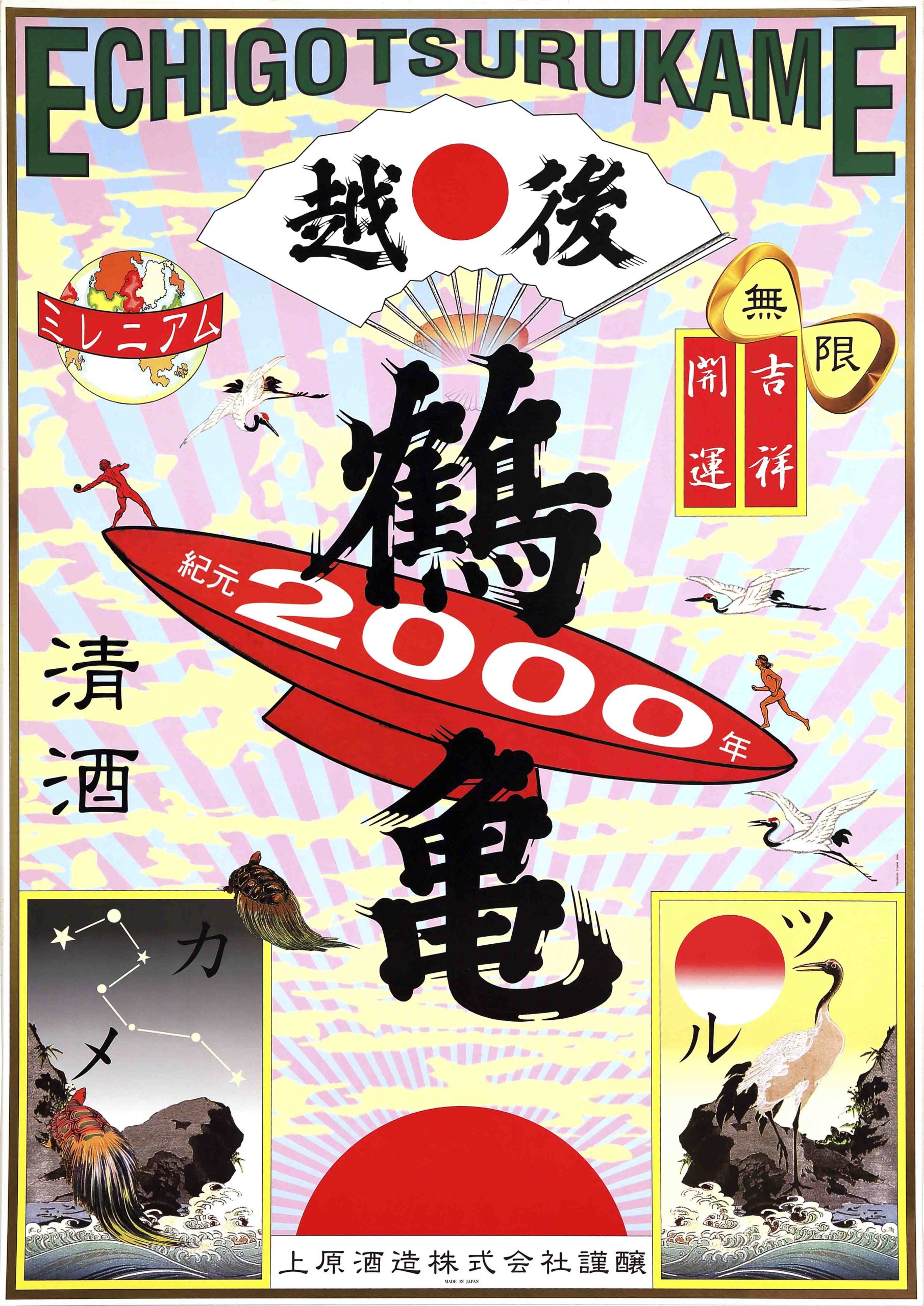

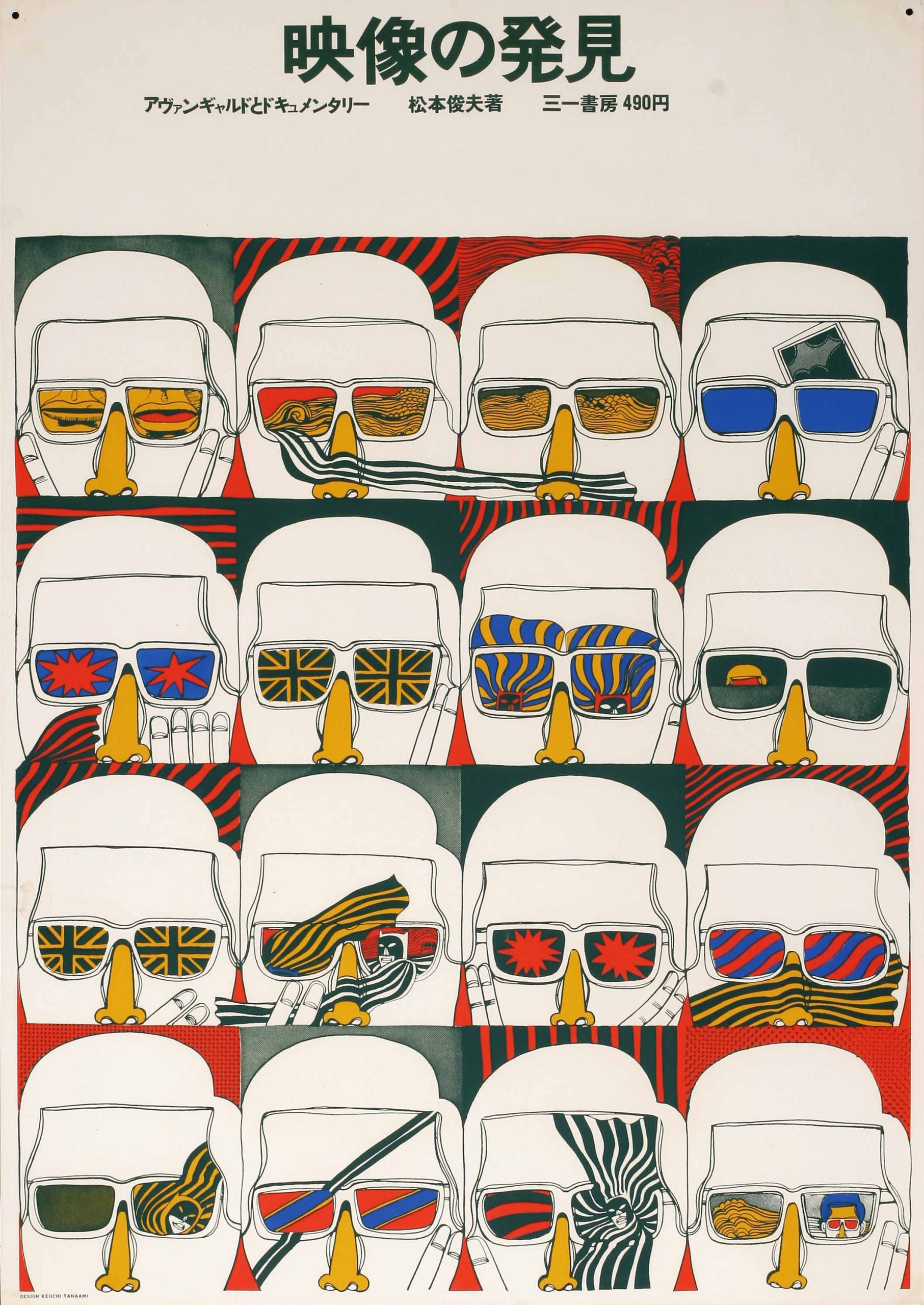

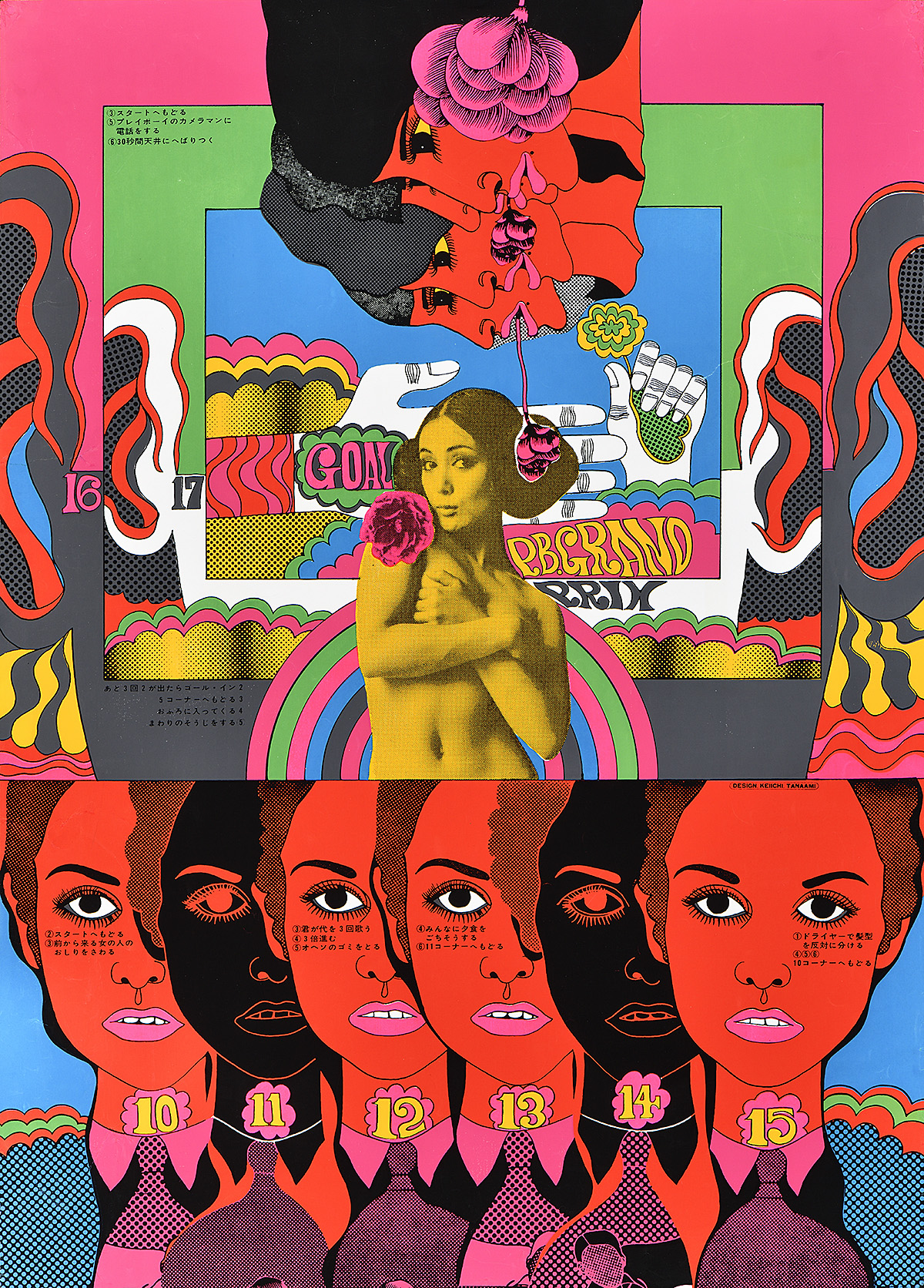

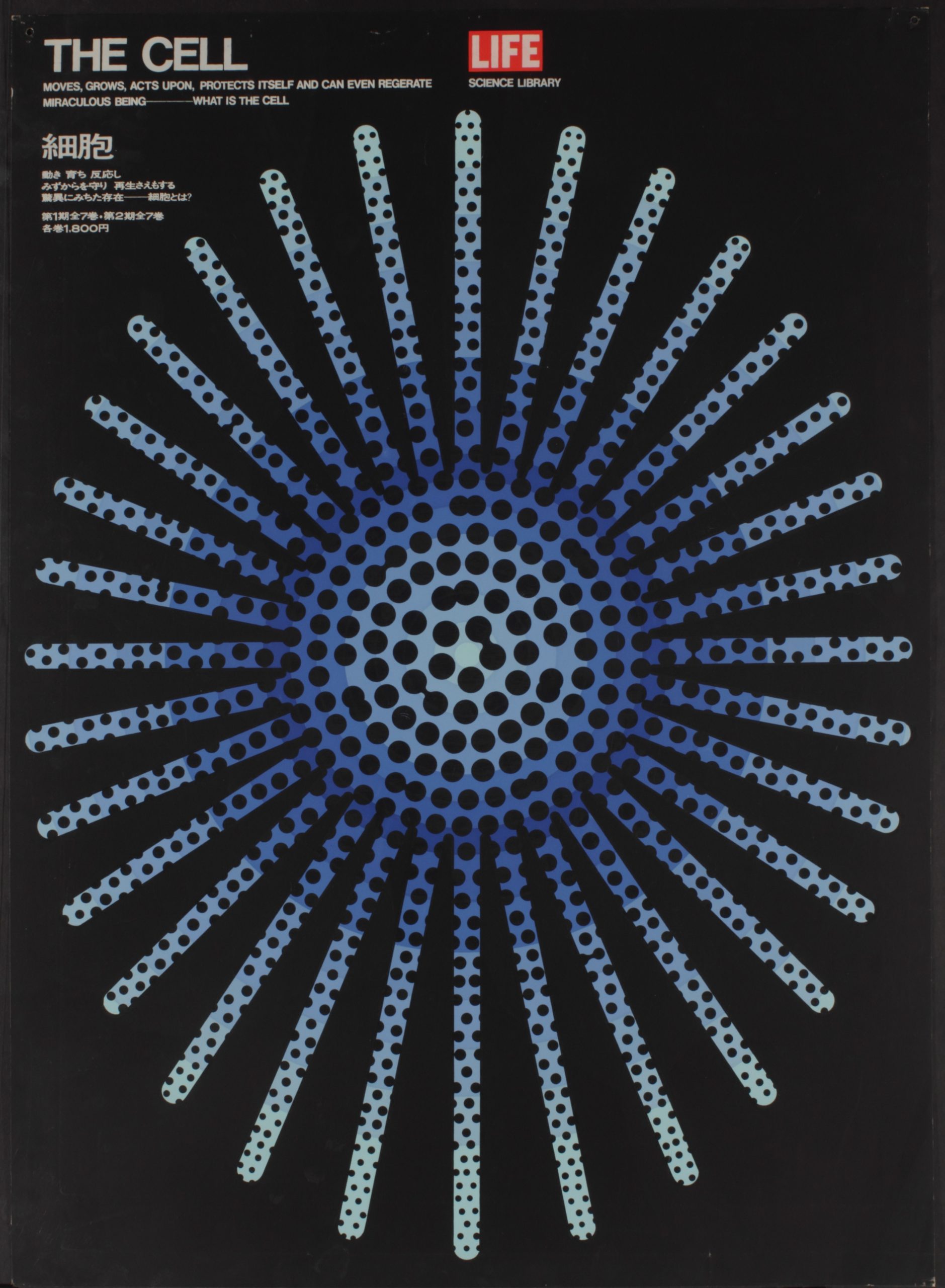

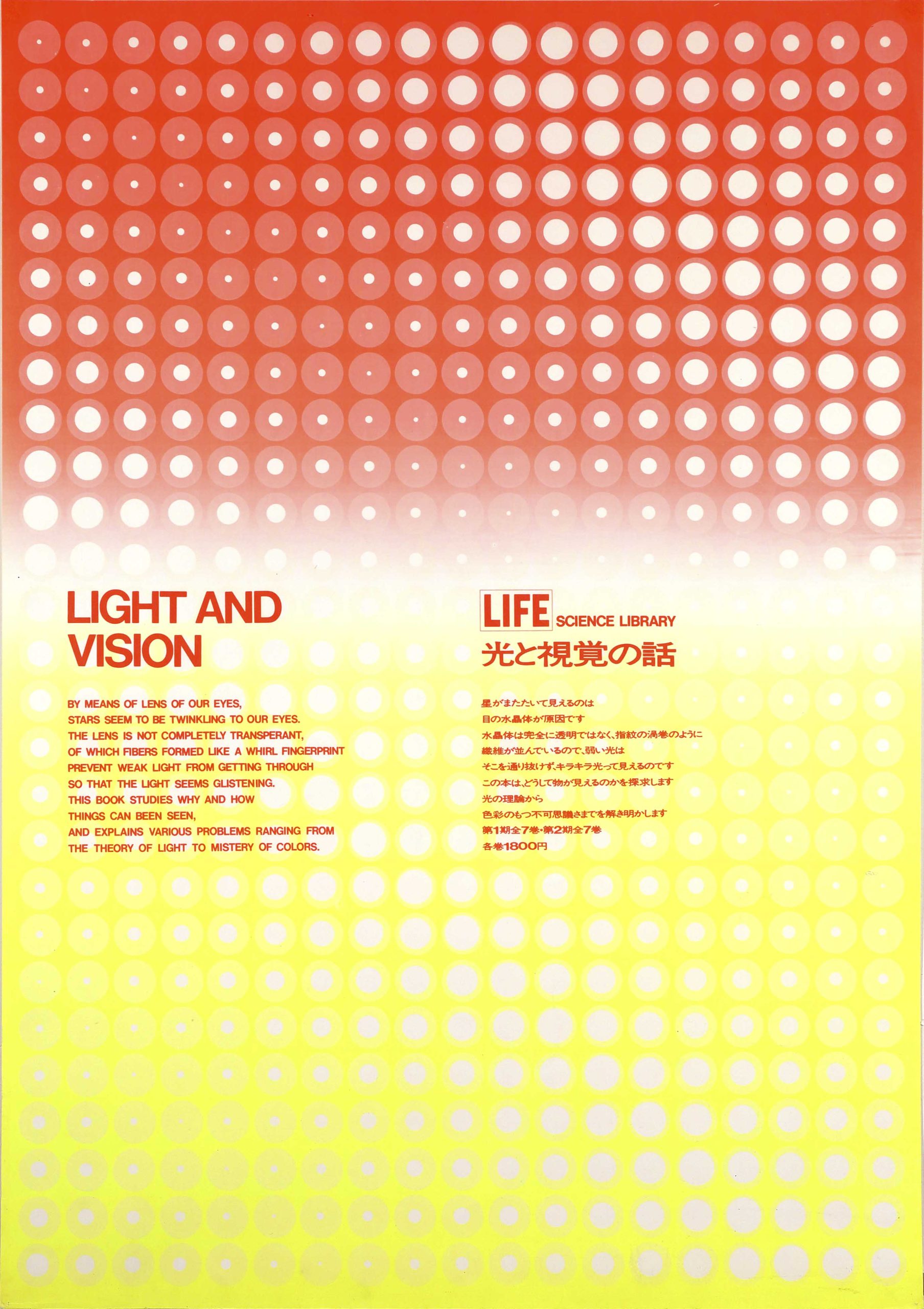

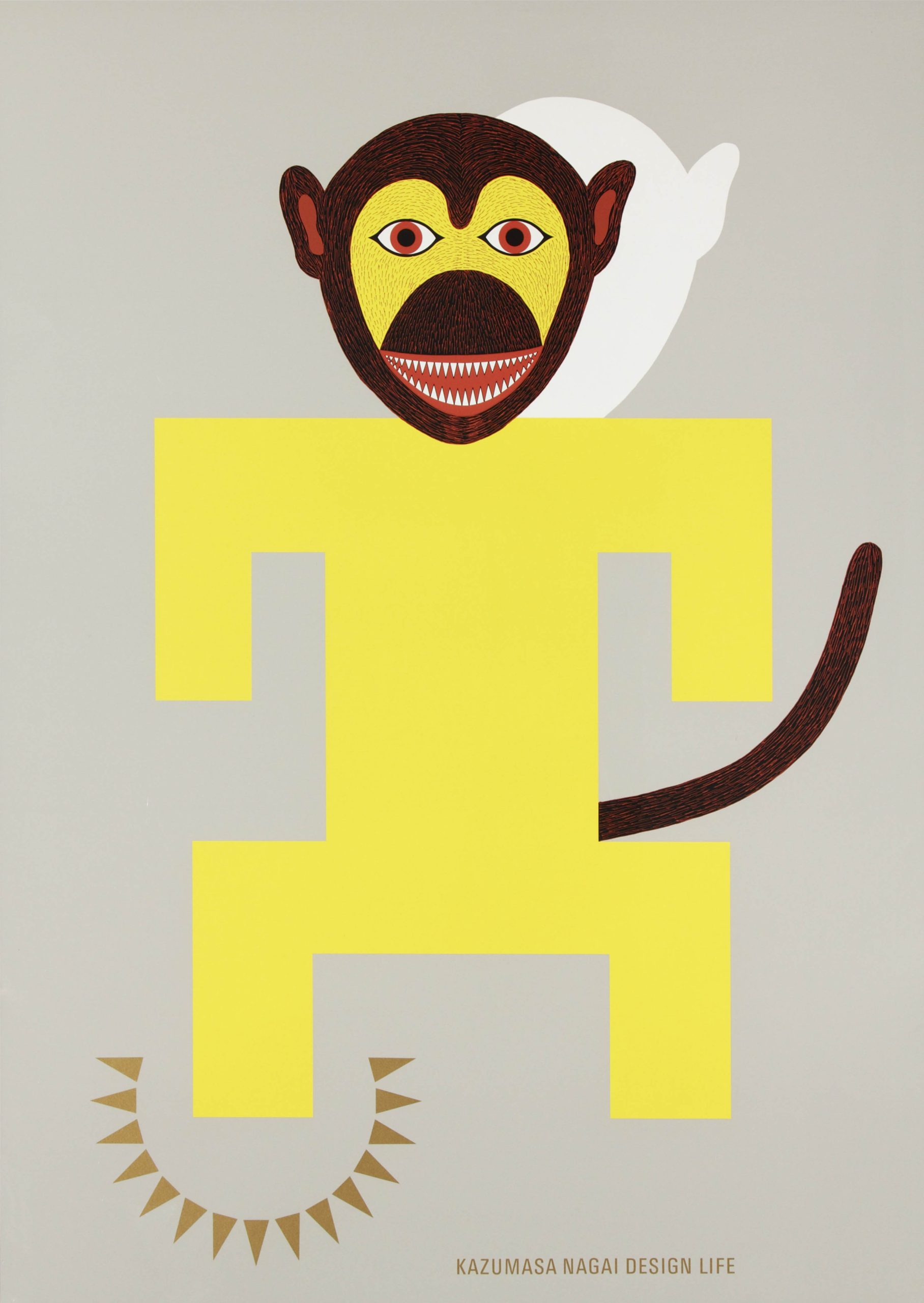

Japanese poster design reflects the country’s rich visual culture and printmaking tradition, and was used throughout the 20th century to represent the country to domestic and international audiences. Two world wars, in addition to rapid industrialization, urbanization, and the rise of mass media fundamentally transformed modern Japan, and its specific journey as both an aggressor and a victim of war reinforced the nation’s efforts to revamp its image. Within this context, posters allowed Japanese artists, designers, corporations, brands, and the government to shape the social, political, and ideological values of the time with compositions that blended elements of traditional and modern design.

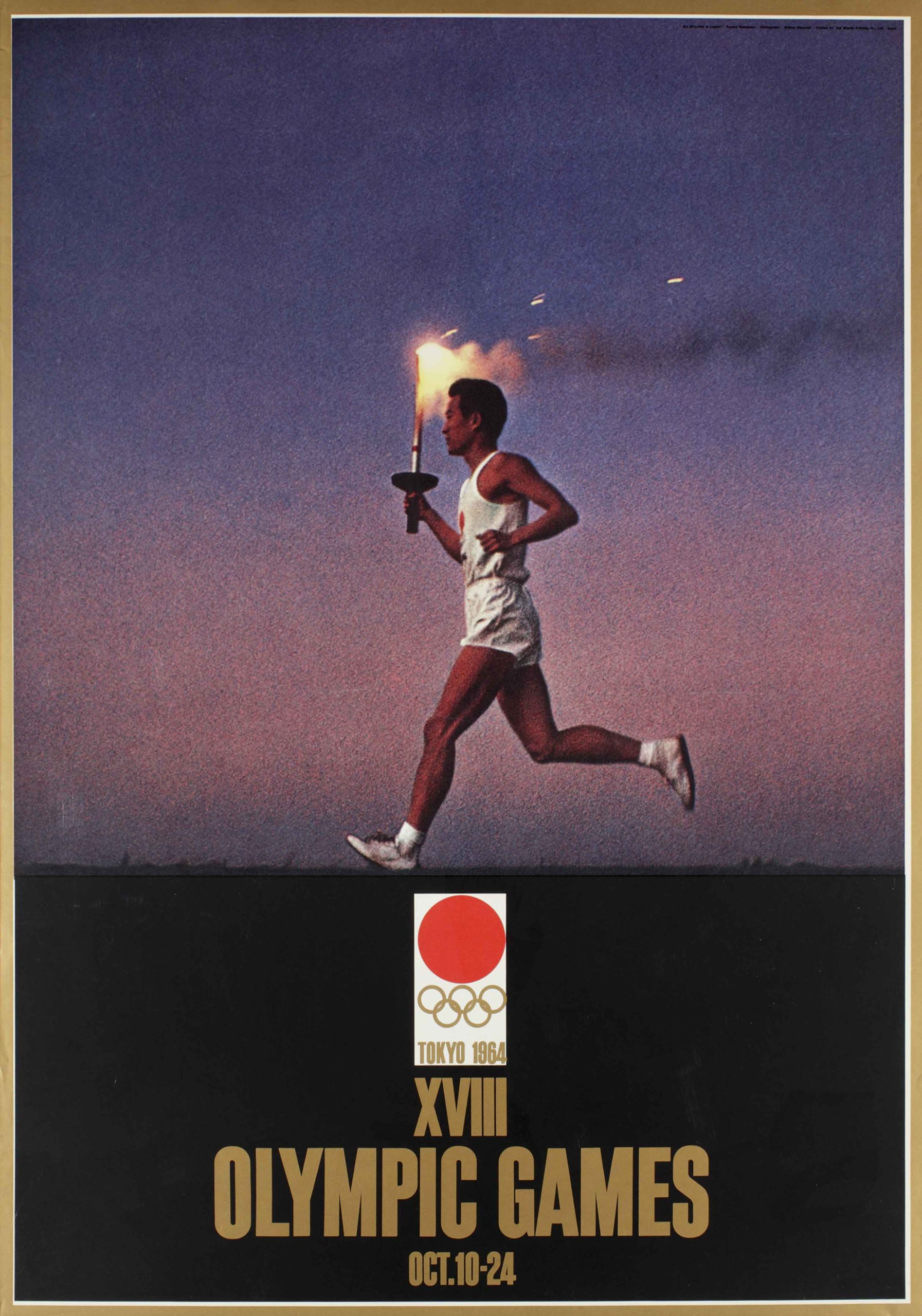

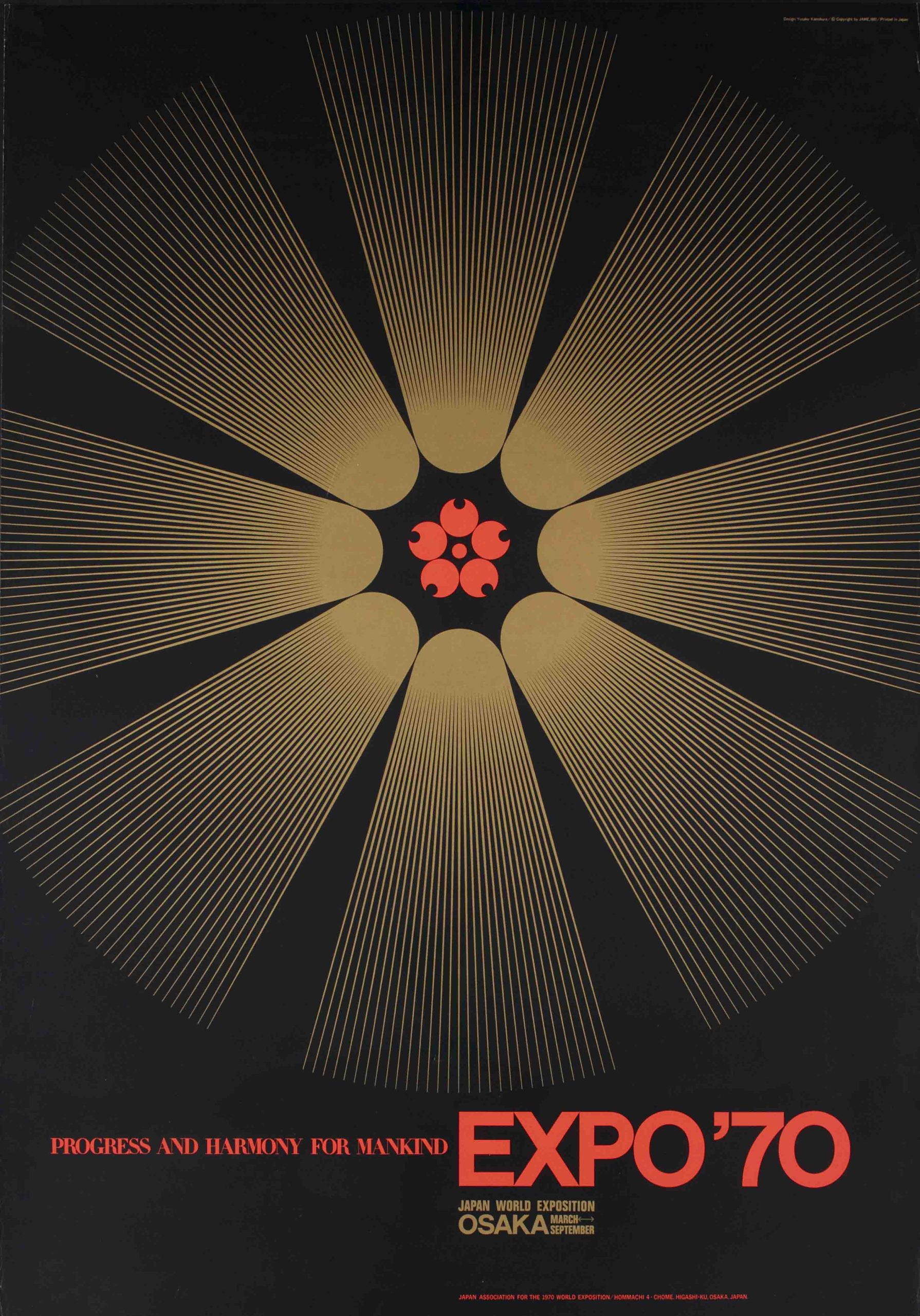

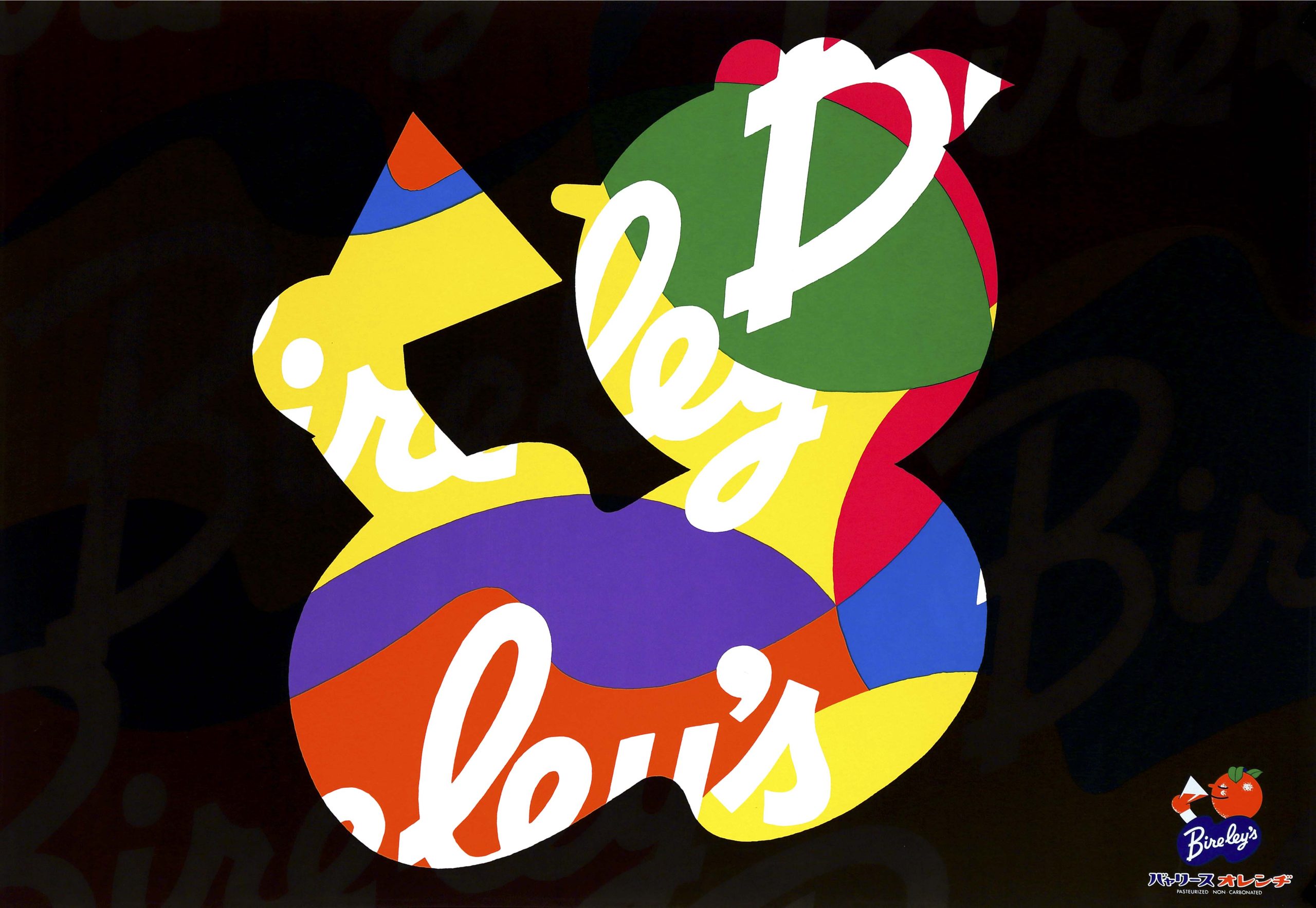

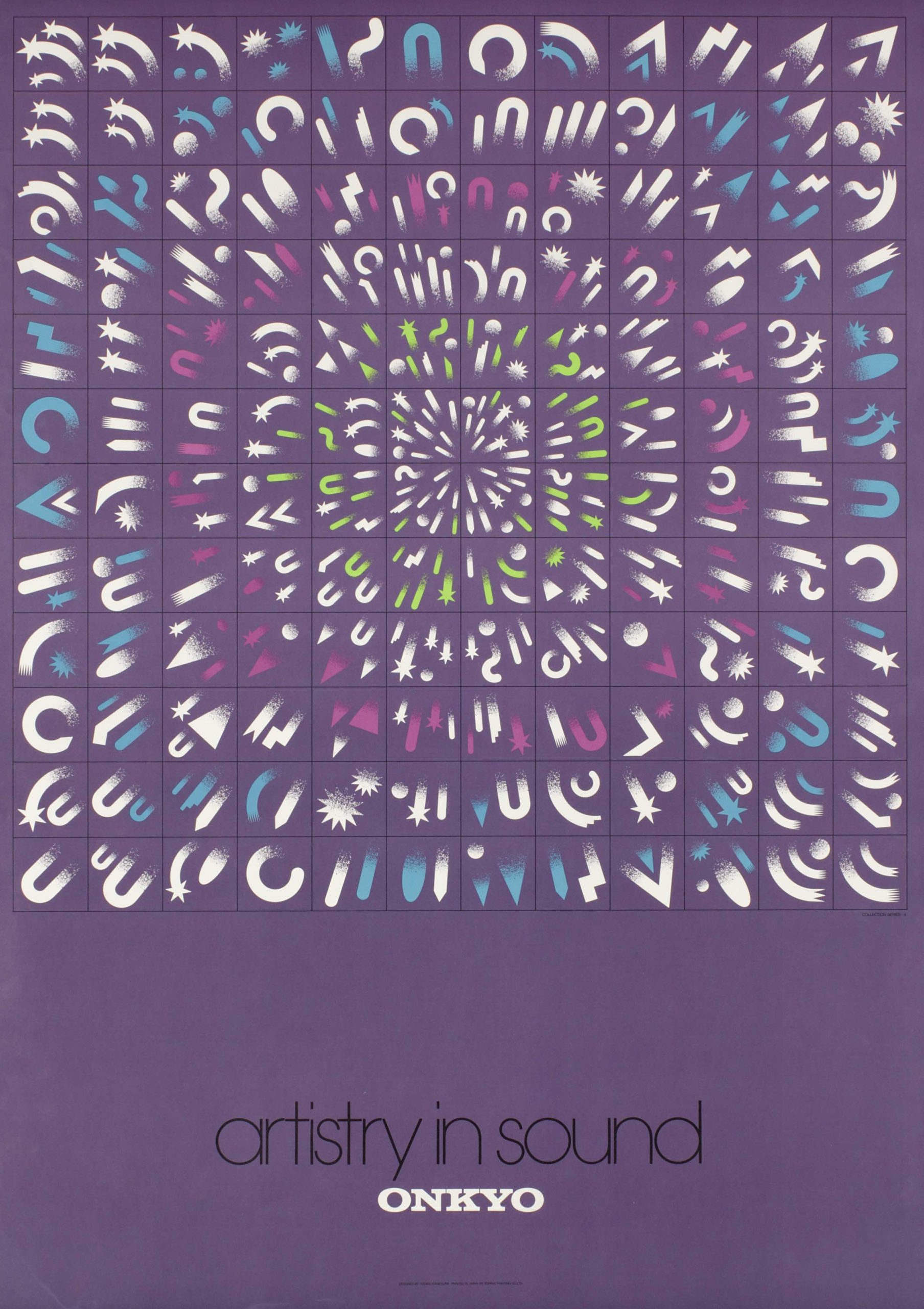

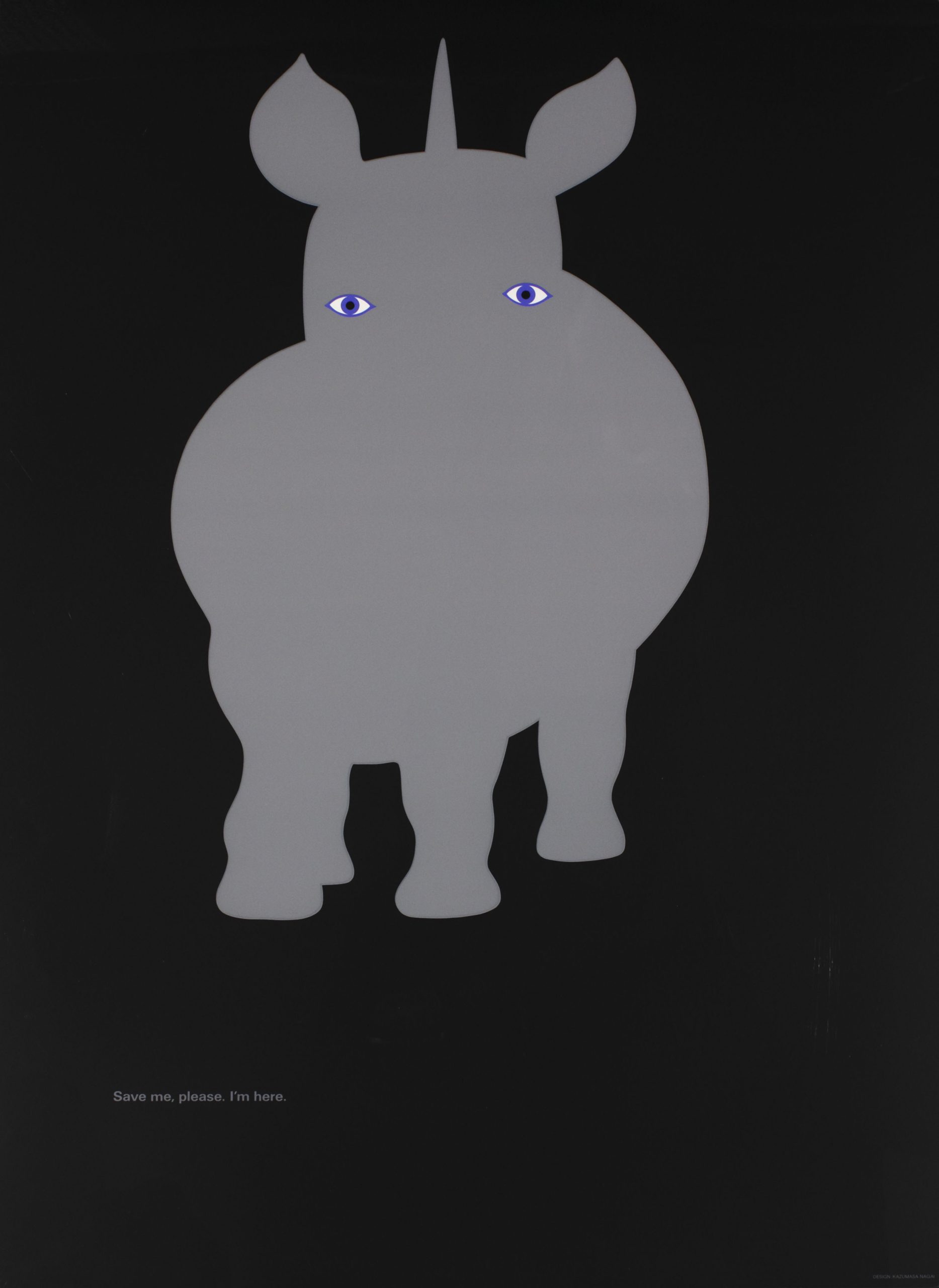

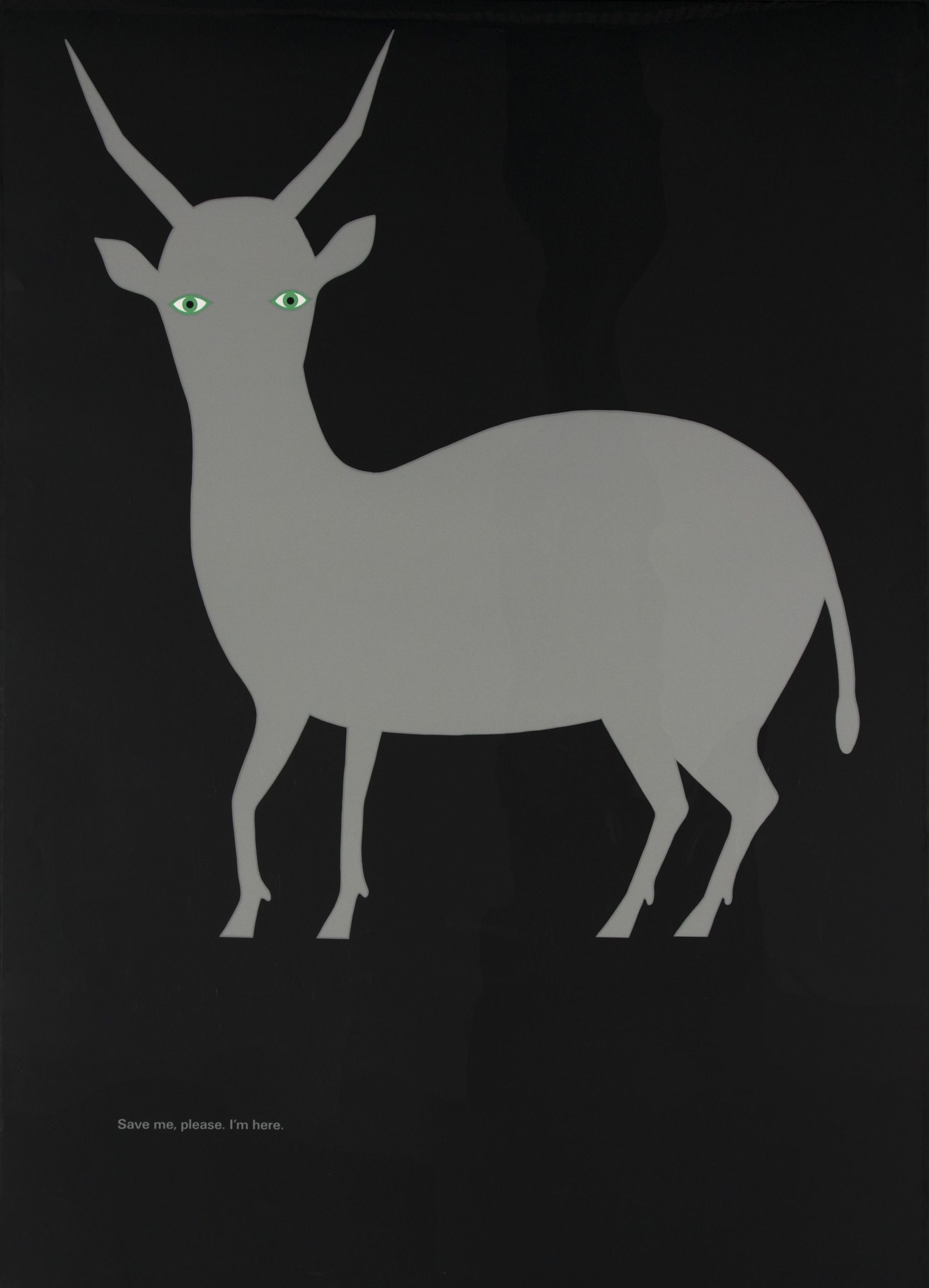

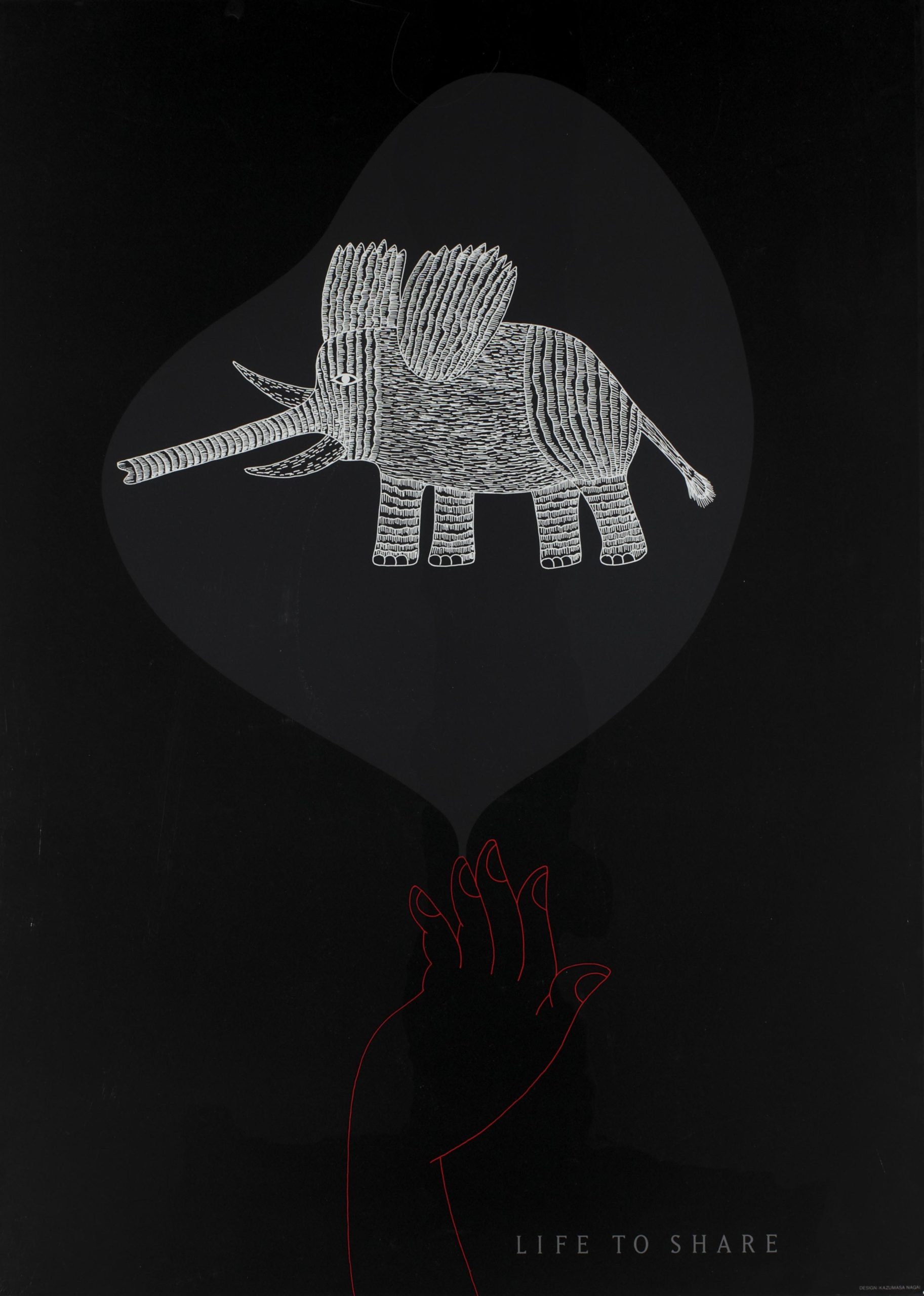

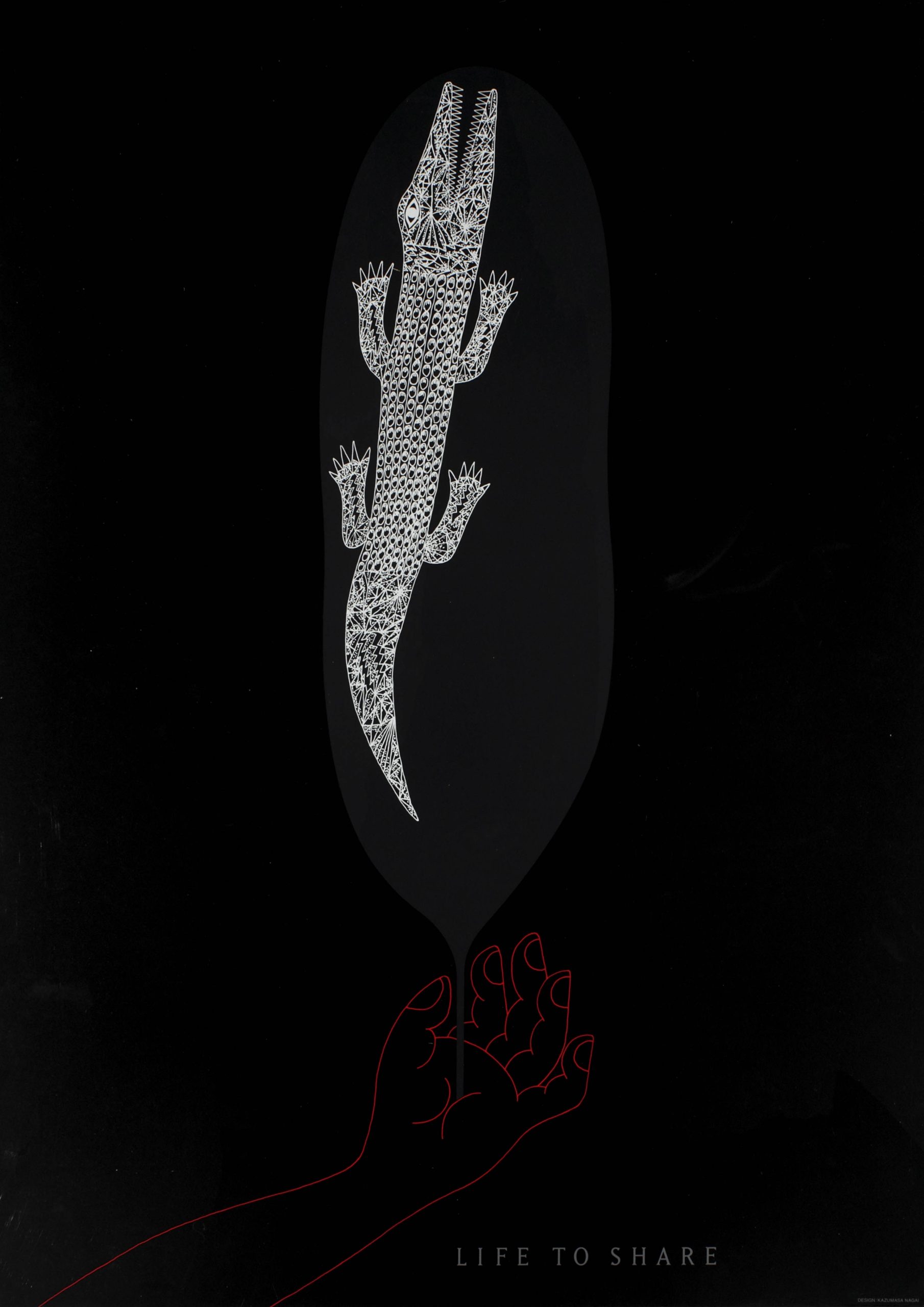

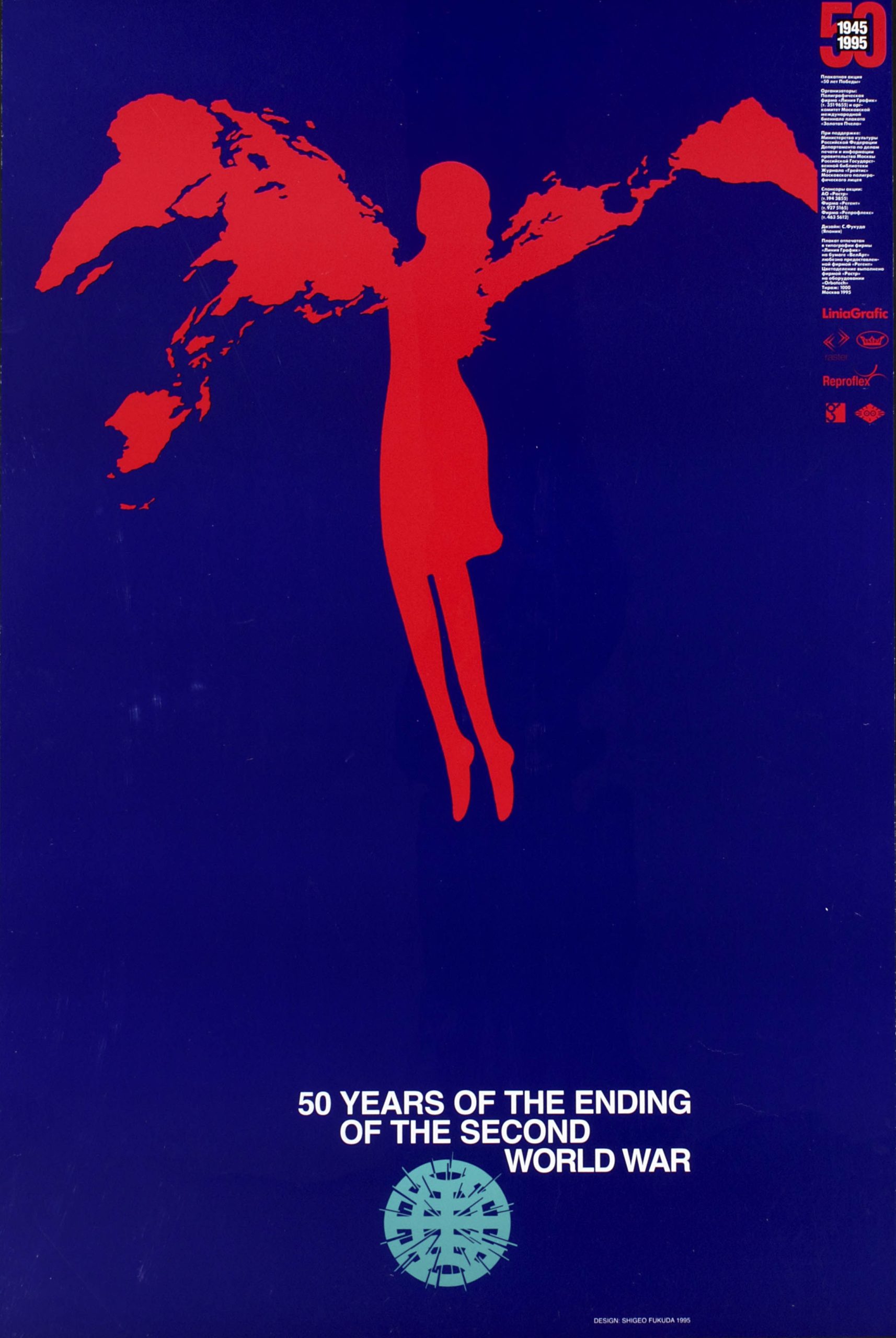

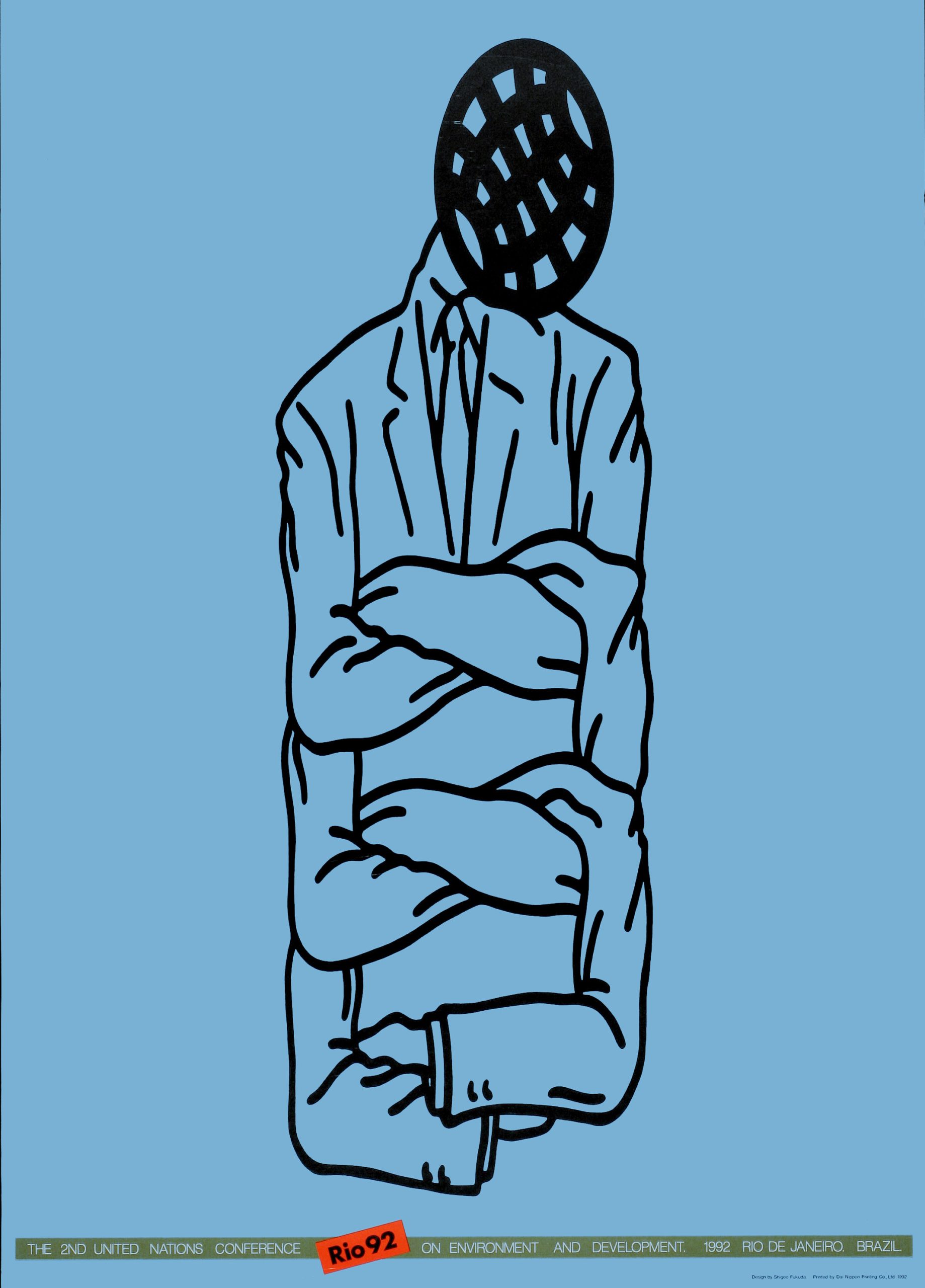

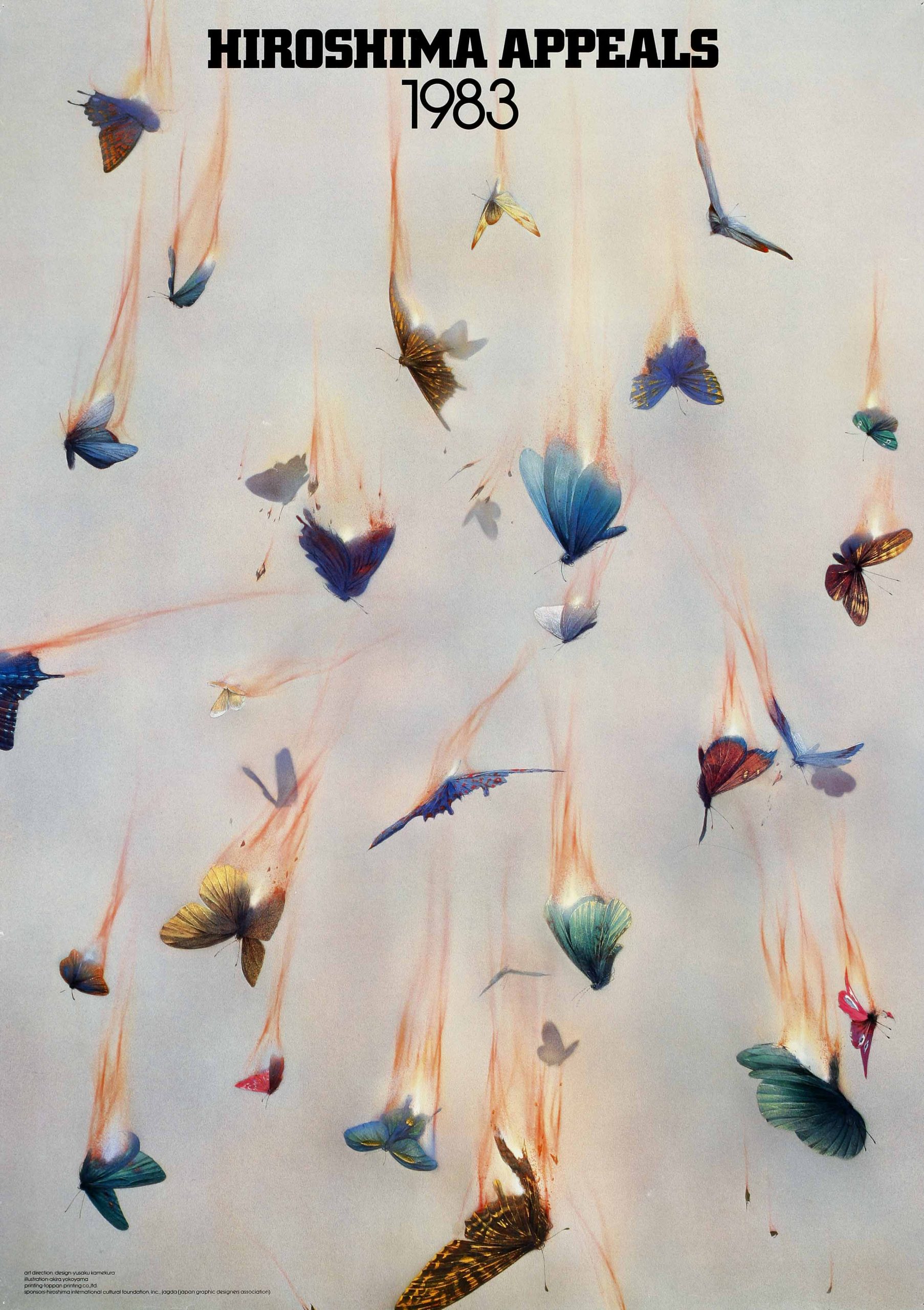

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) and World War II (1939–45), posters were intended to inspire patriotism, circulate propaganda, and encourage consumer restraint in support of the war effort. During the postwar period, however, unparalleled growth in the manufacturing sector catapulted the Japanese economy to the position of second largest in the world, creating limitless opportunities for poster advertising as Japanese corporations became both household names and global brands. Following the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1970 Osaka World Expo, Japan’s international standing shifted again, emboldening Japanese artists and designers to conceive new forms of graphic media that combined a traditional Japanese aesthetic with Western design idioms. Between the 1980s and the early 21st century, Japanese posters functioned beyond the realm of the merely commercial, allowing designers to address such social issues as pollution, climate change, sustainability, nuclear disarmament, and global peace and reconciliation.

This exhibition explores the cultural and political shifts within modern Japan that influenced the functions and messaging of its advertising posters, and the public’s response to them.

Unless otherwise noted, all items come to Poster House through a generous loan from the Merrill C. Berman Collection.