Experimental Marriage: Women in Early Hollywood

In the early days of the American film industry, it was common for women to hold a variety of jobs, including those of producer, director, editor, and writer. The unregulated, nonunionized status of this burgeoning field during the 1910s and ’20s meant that there were fewer barriers to entry; this allowed women the opportunity to excel both on and off camera, particularly on the coasts in California, New York, and New Jersey where new cinema hubs were being developed. This halcyon period of relative freedom, was short lived, however. As Hollywood grew and investors saw cinema as a means of reaping large profits, studios began to focus on producing fewer movies with bigger budgets and more popular content. Industry positions that had once been more permeable, often covering multiple jobs, were now defined by unions and stricter corporate oversight, always with an eye on the bottom line. By the 1930s, many of the earliest female directors, producers, and writers were being forced out, with no younger generation poised to replace them. This shift in the structure of film production from a collaborative, experimental endeavor toward one that operated as a vertically integrated business effectively eliminated women, creating an “old boys’ network” that persists today.

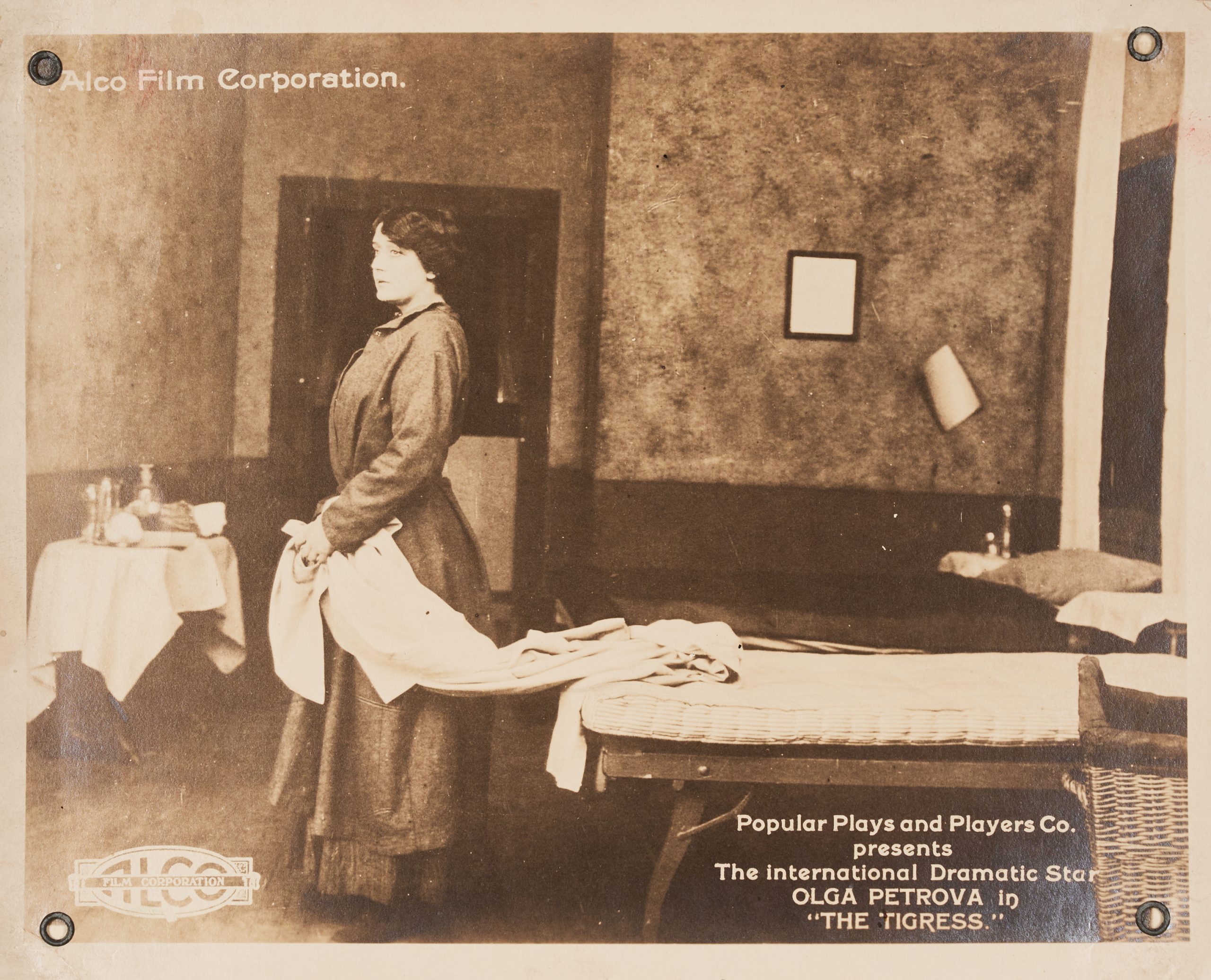

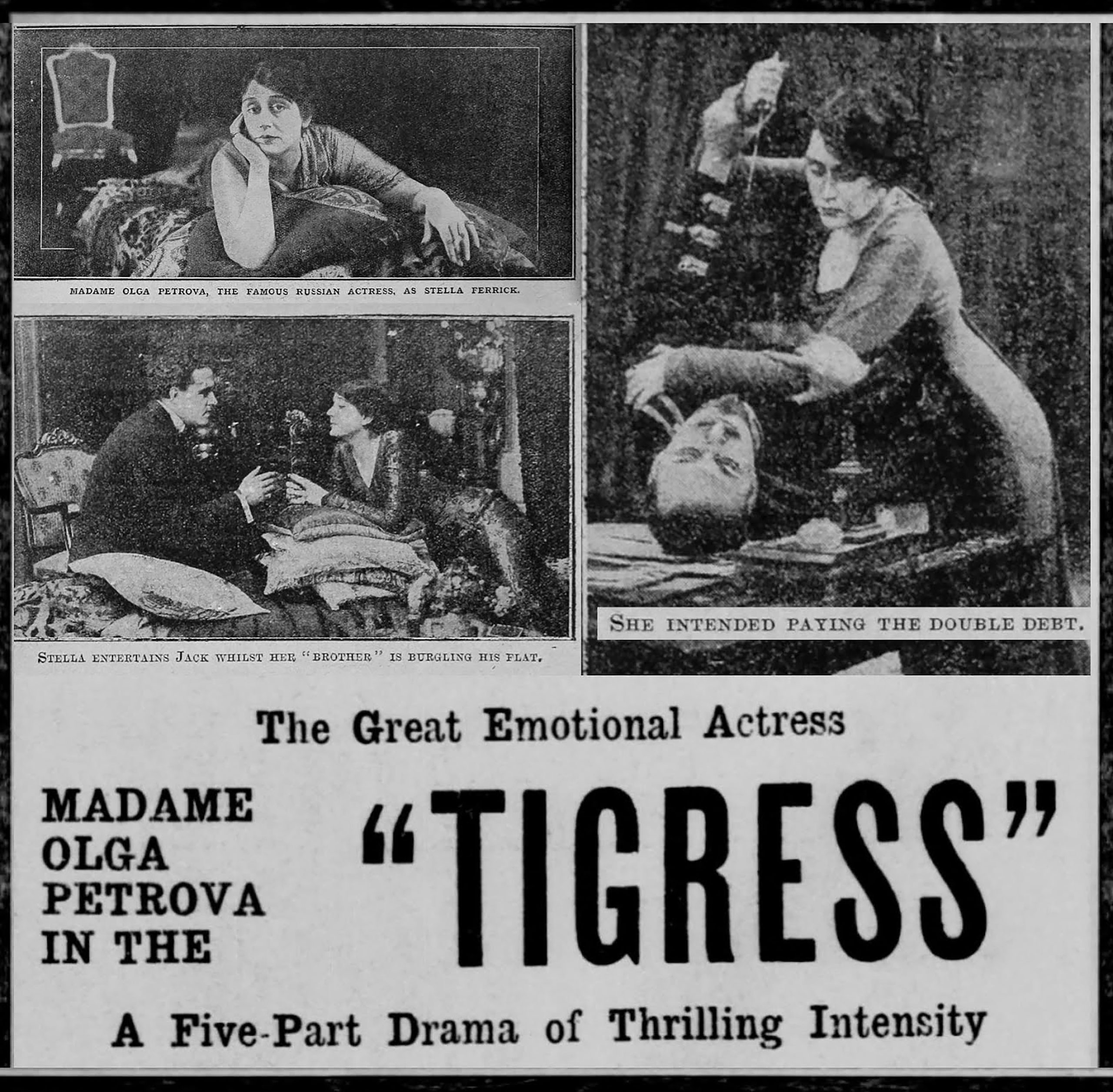

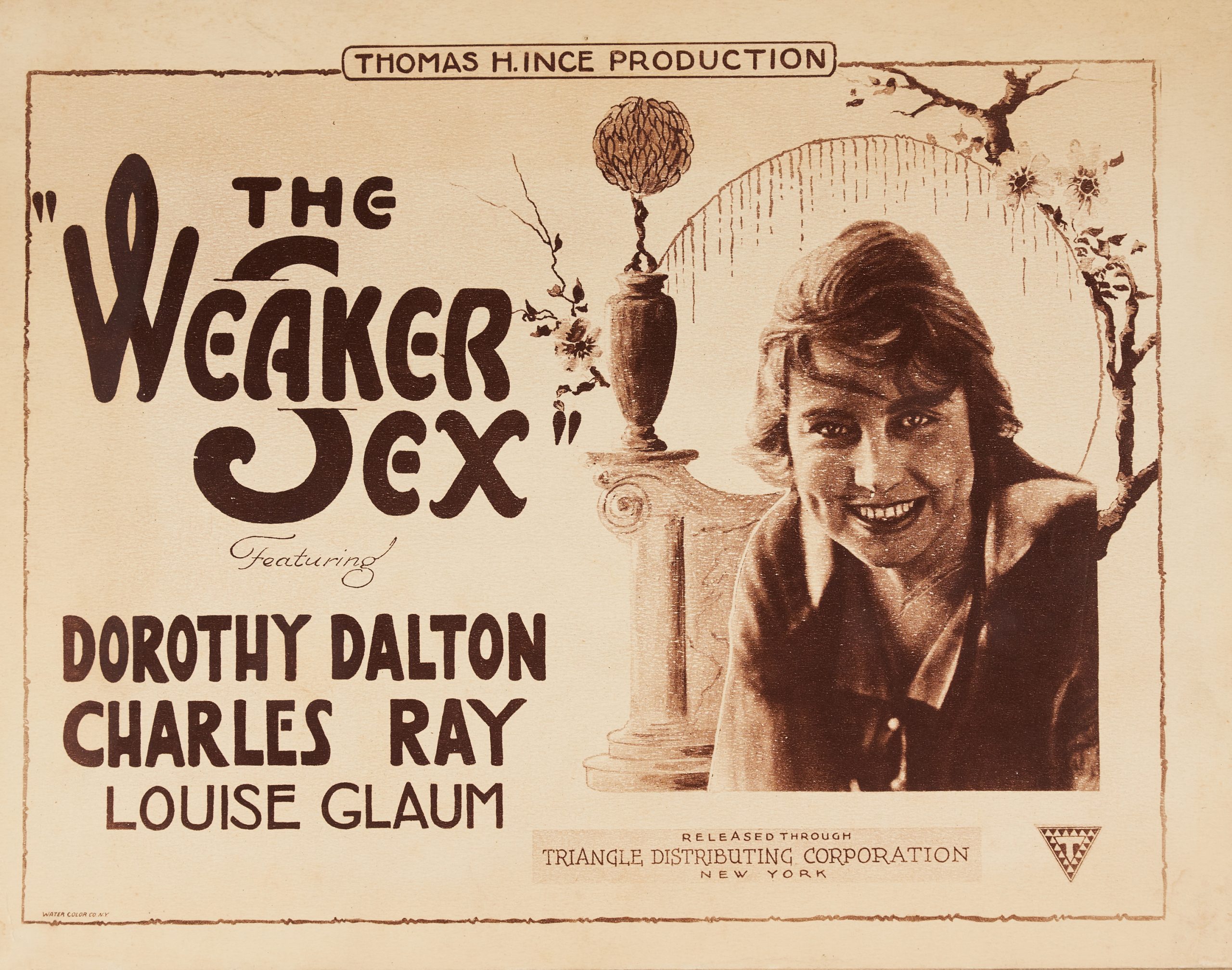

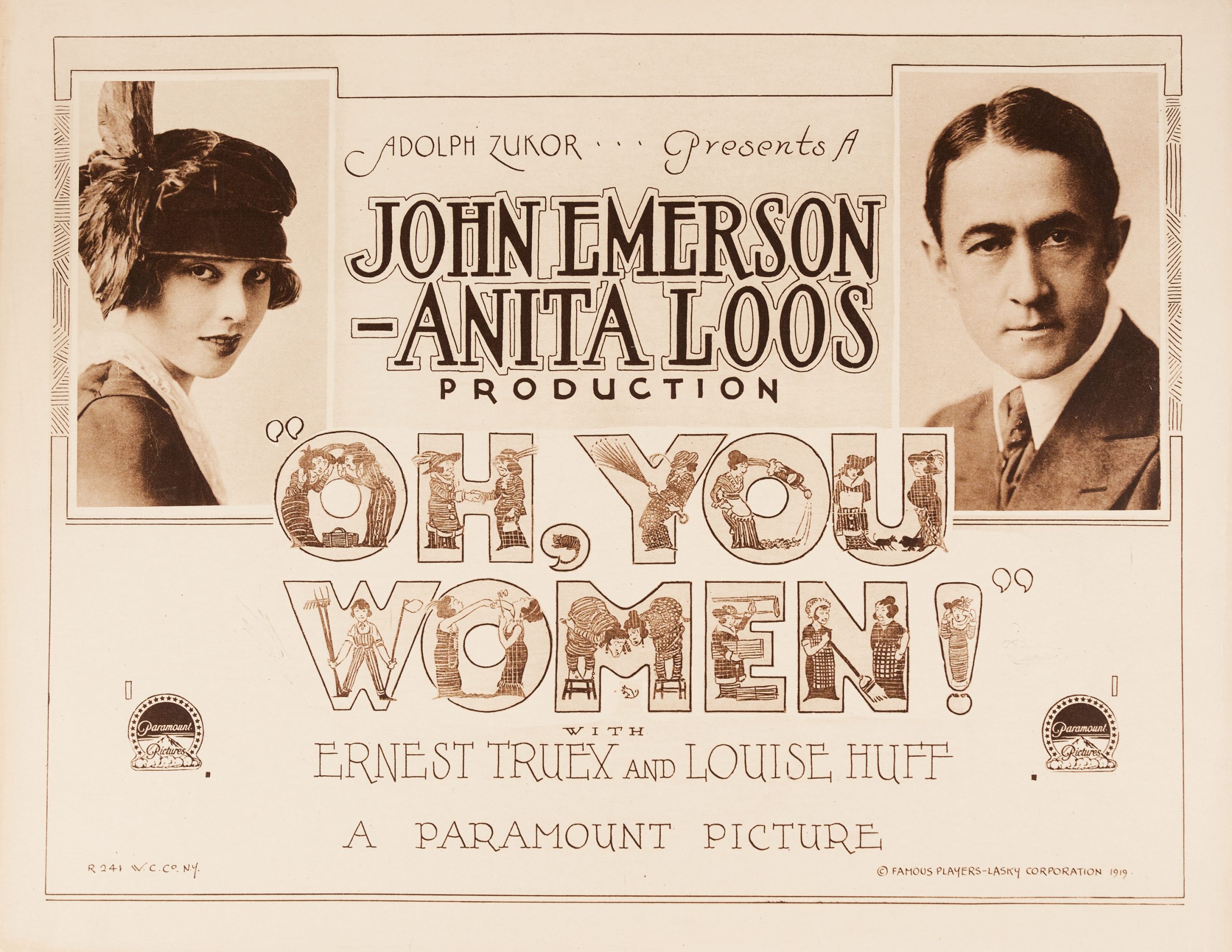

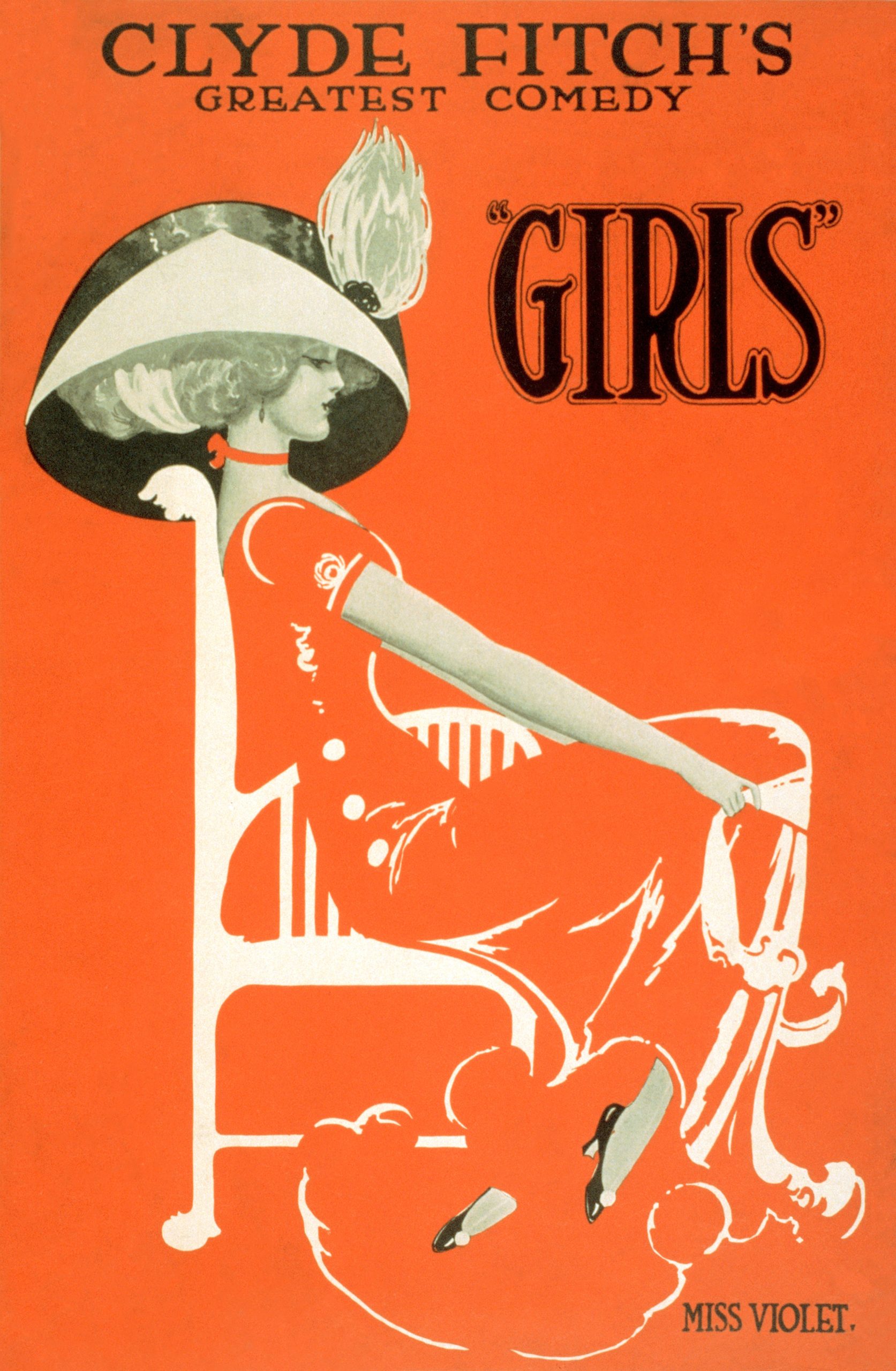

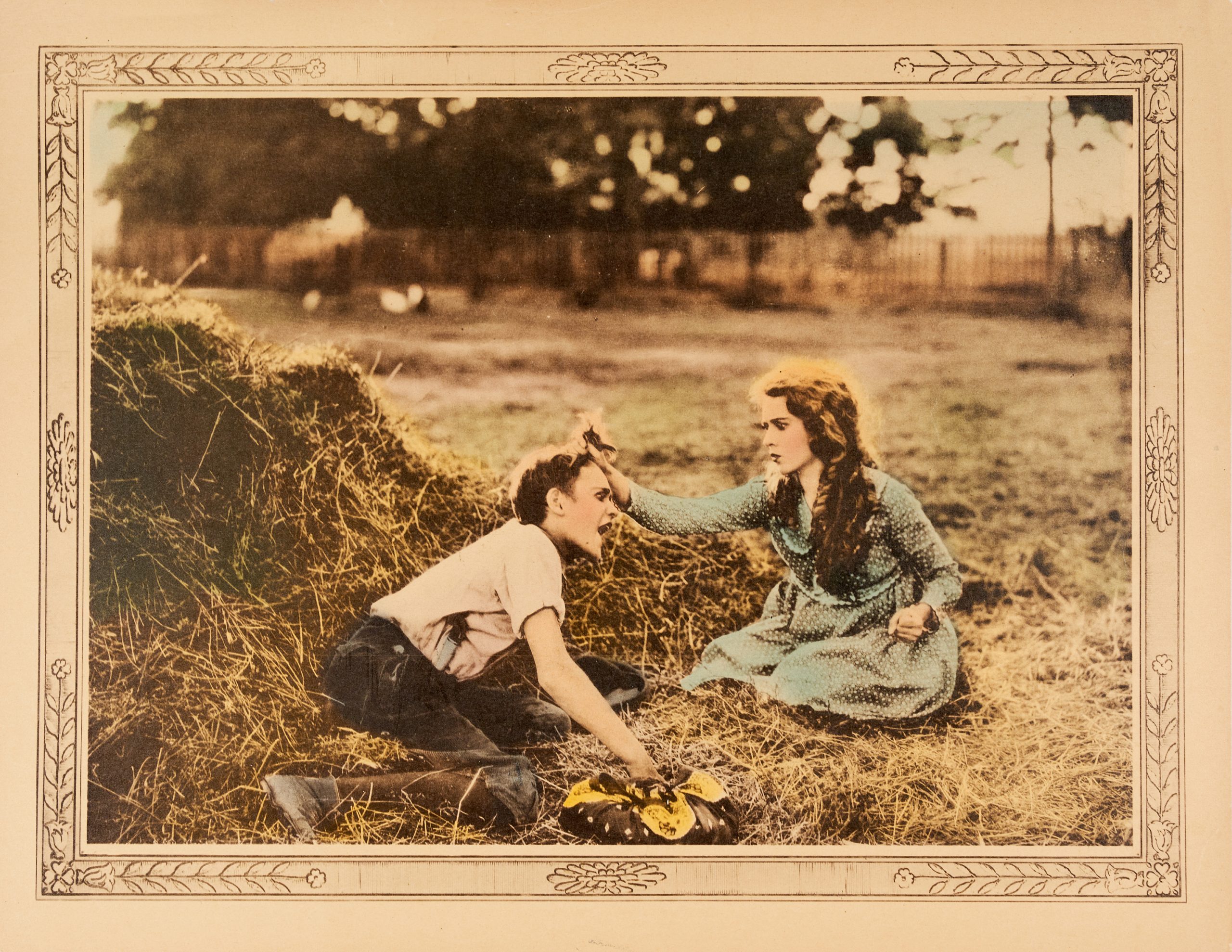

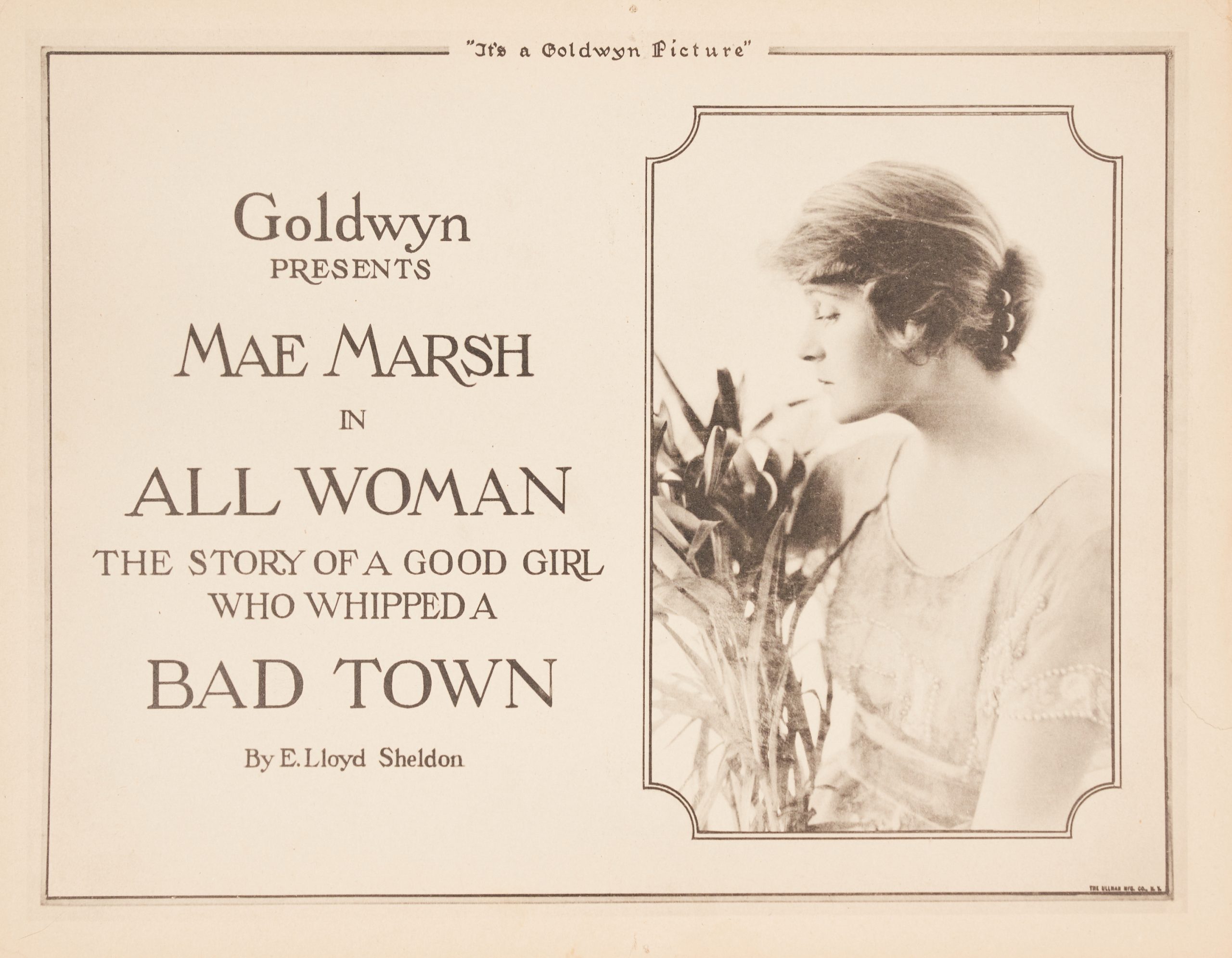

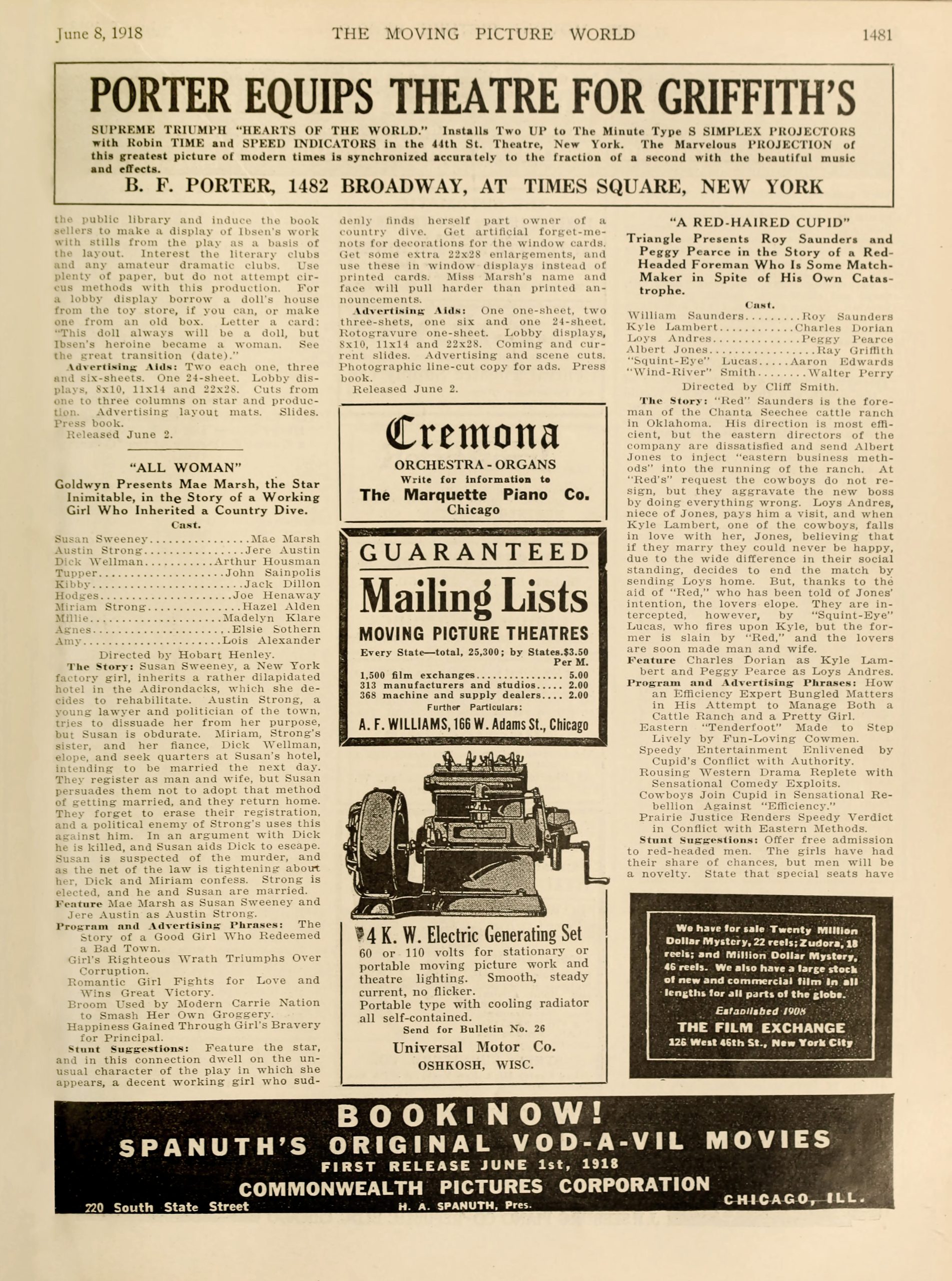

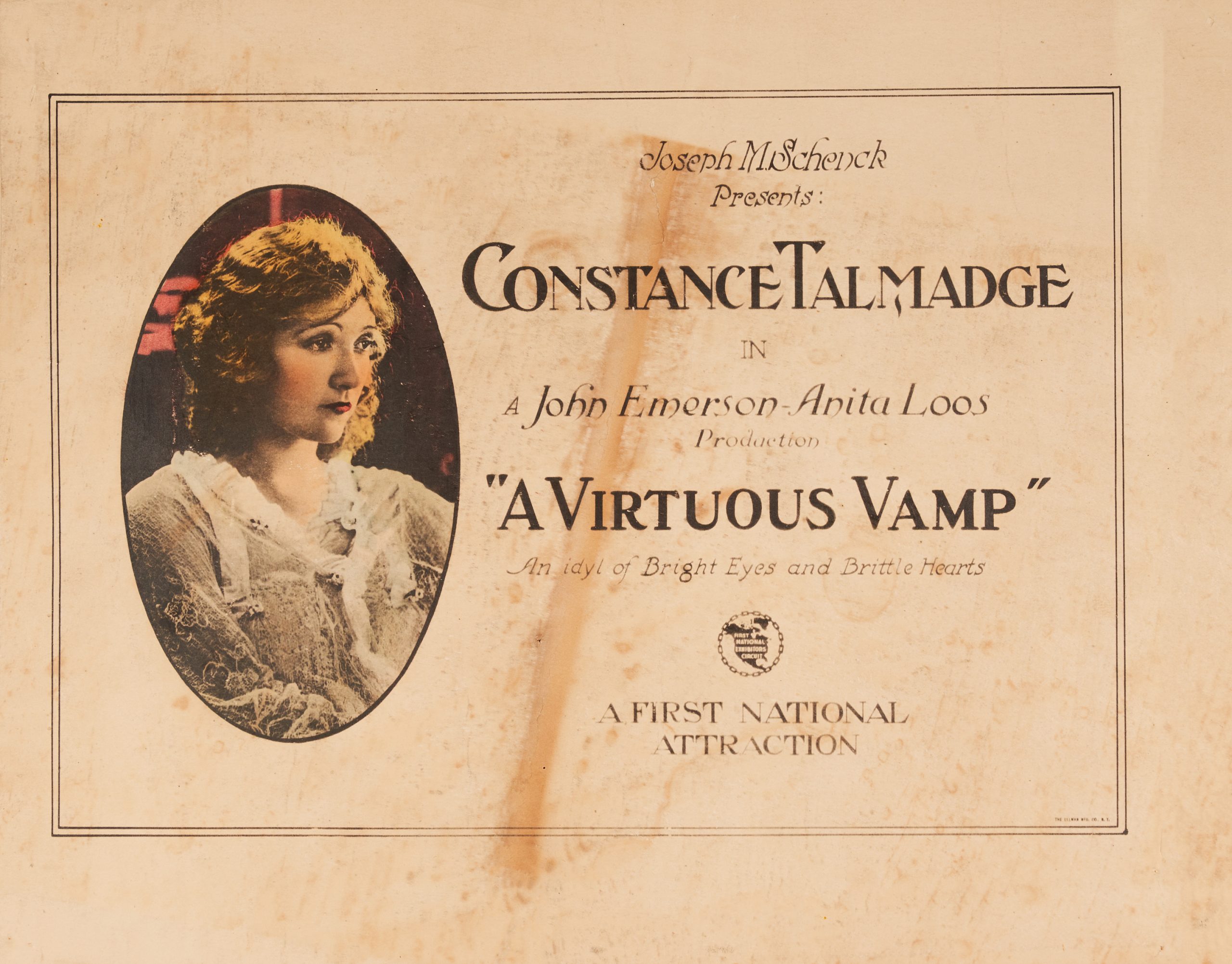

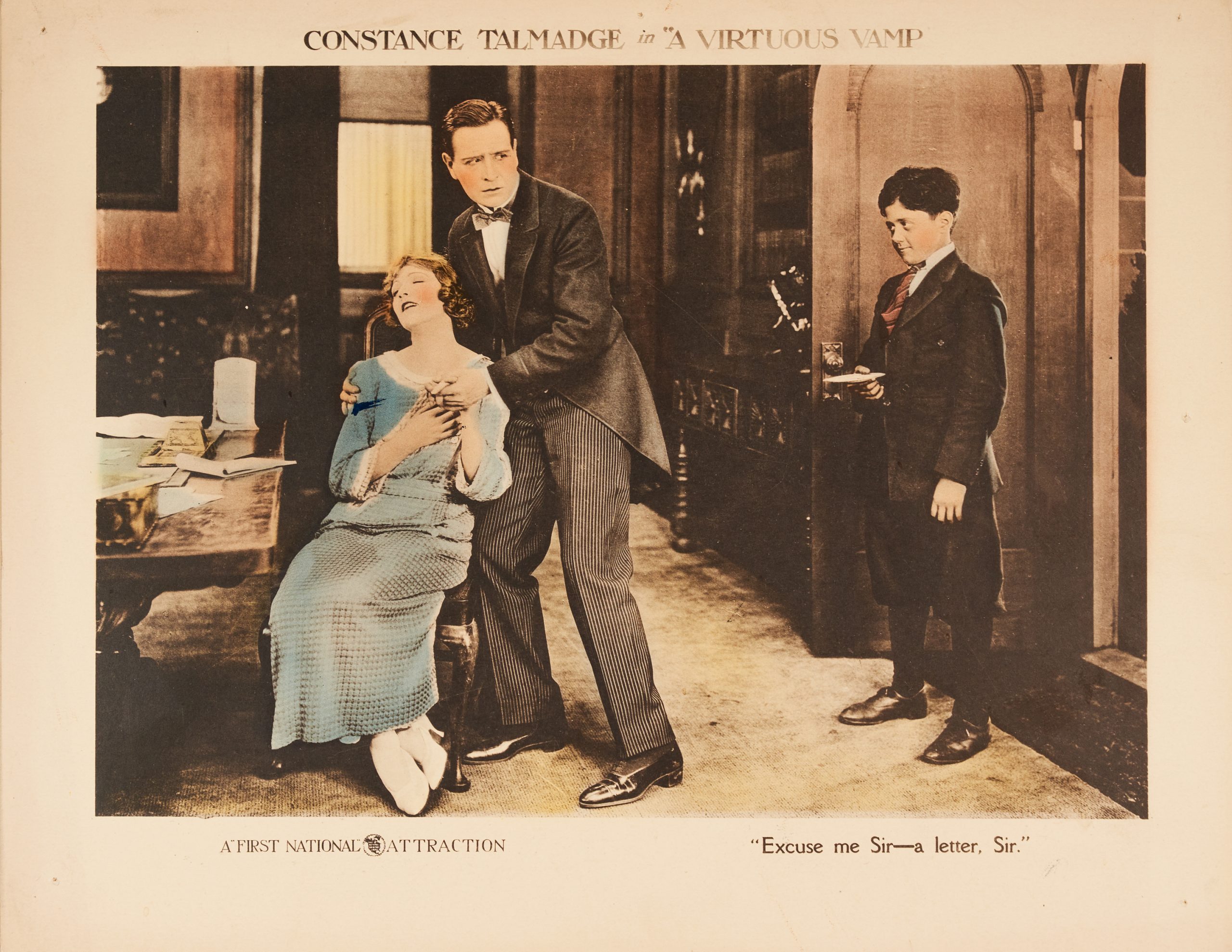

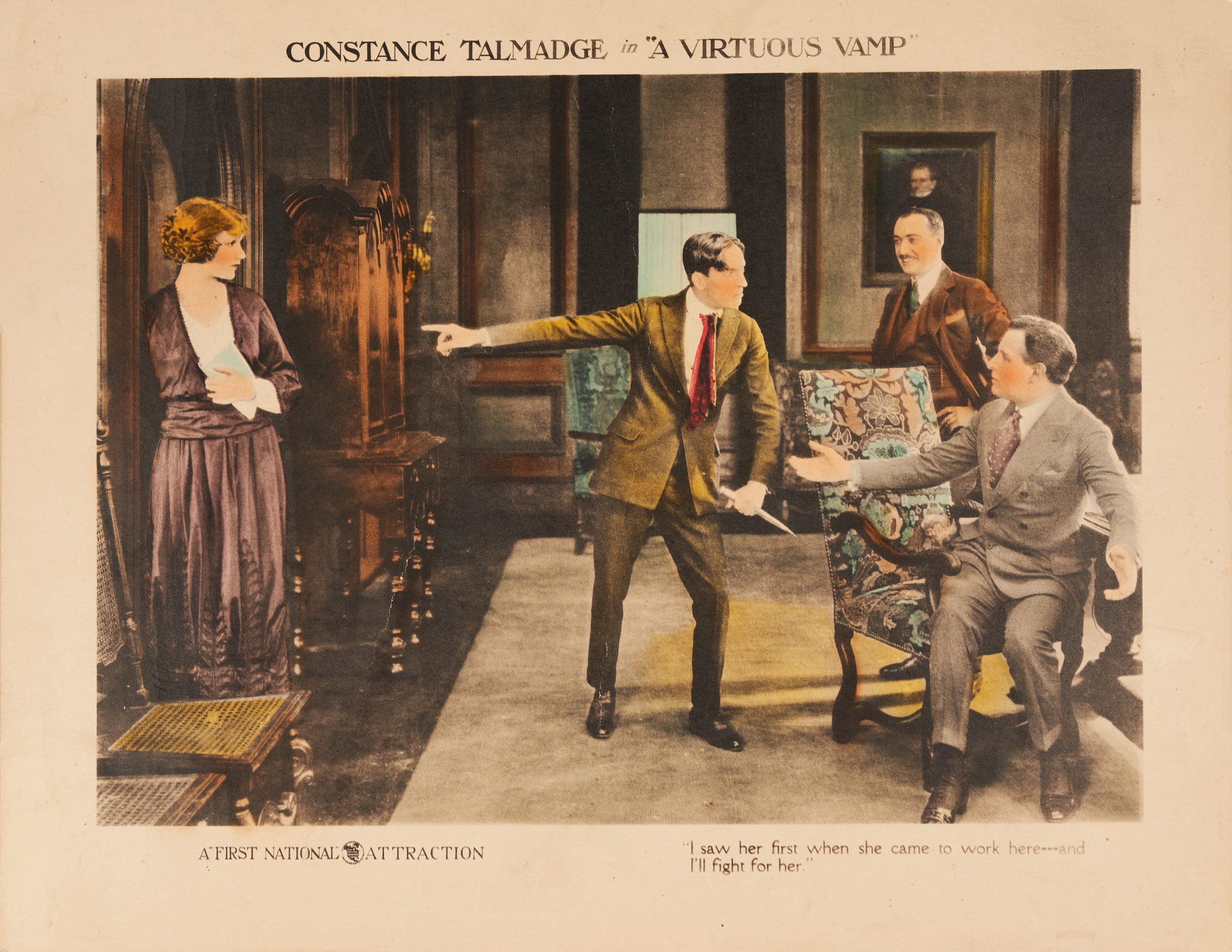

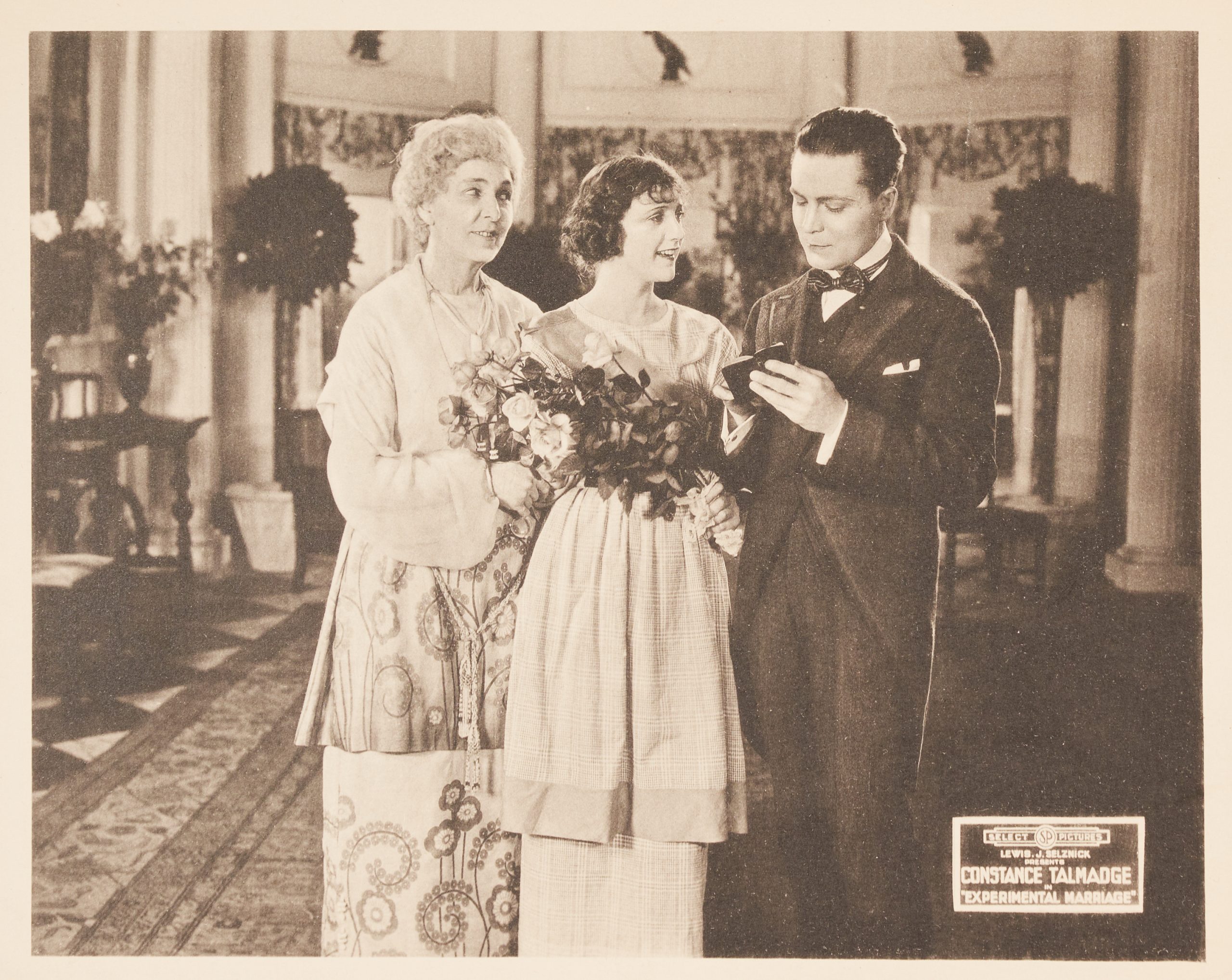

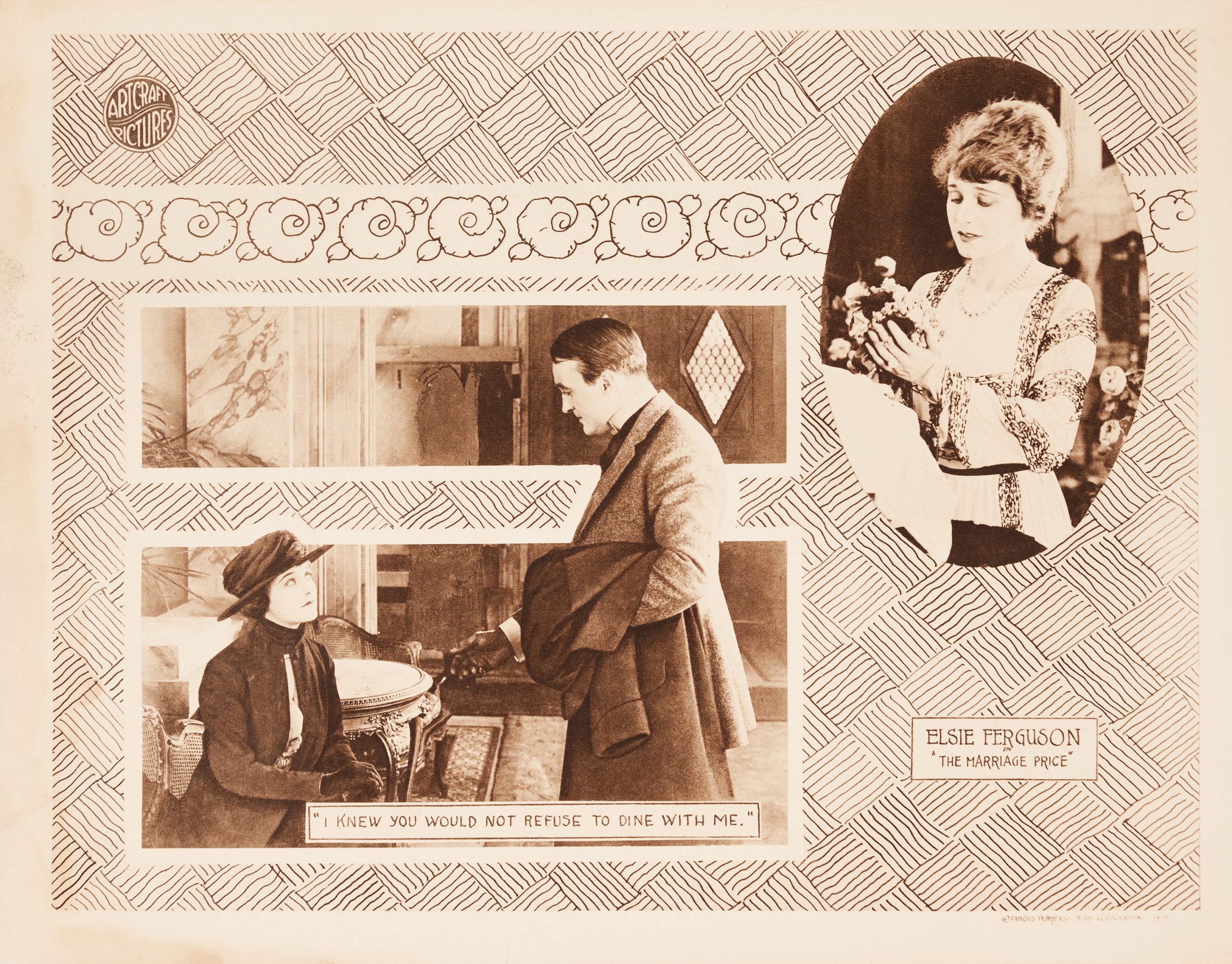

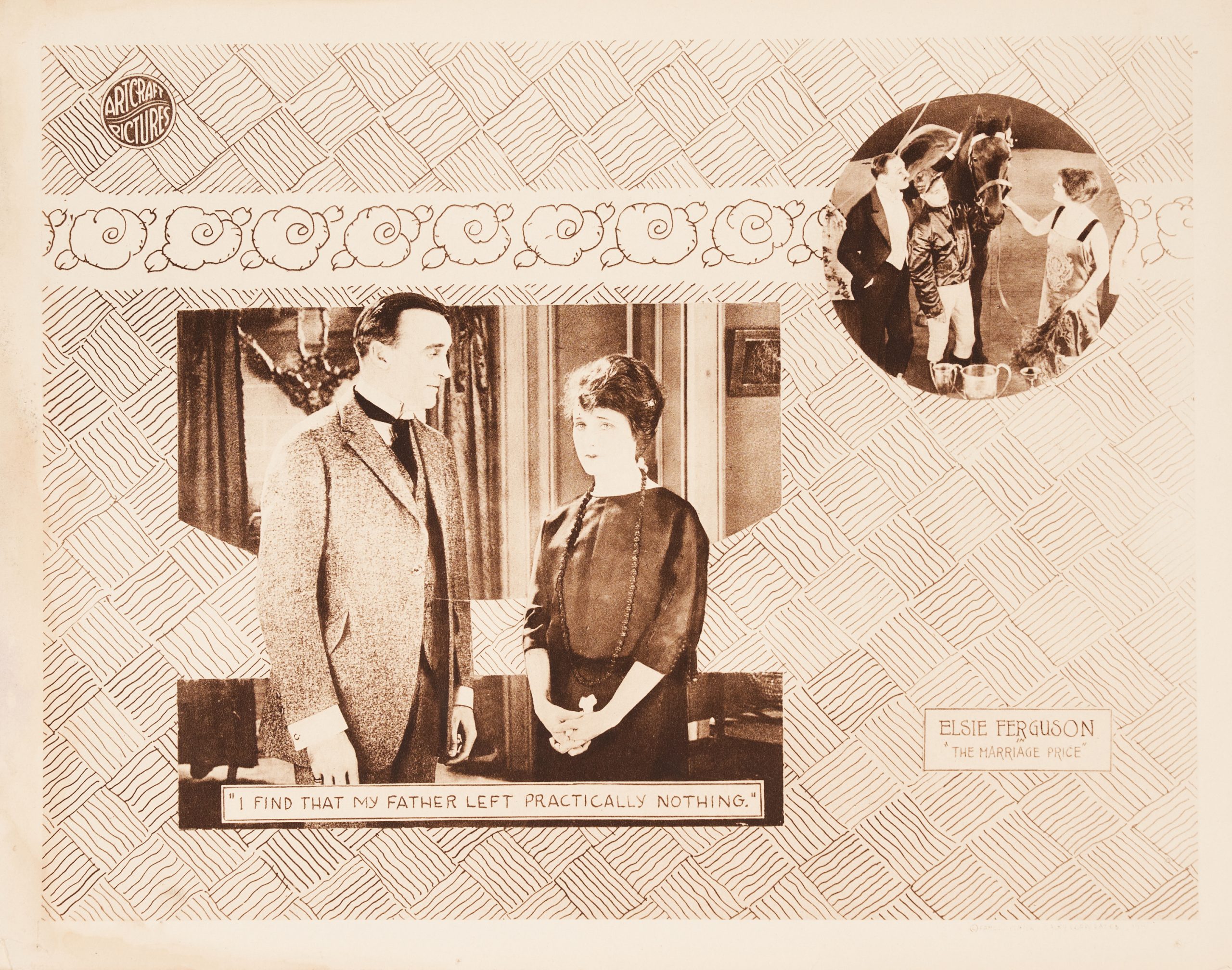

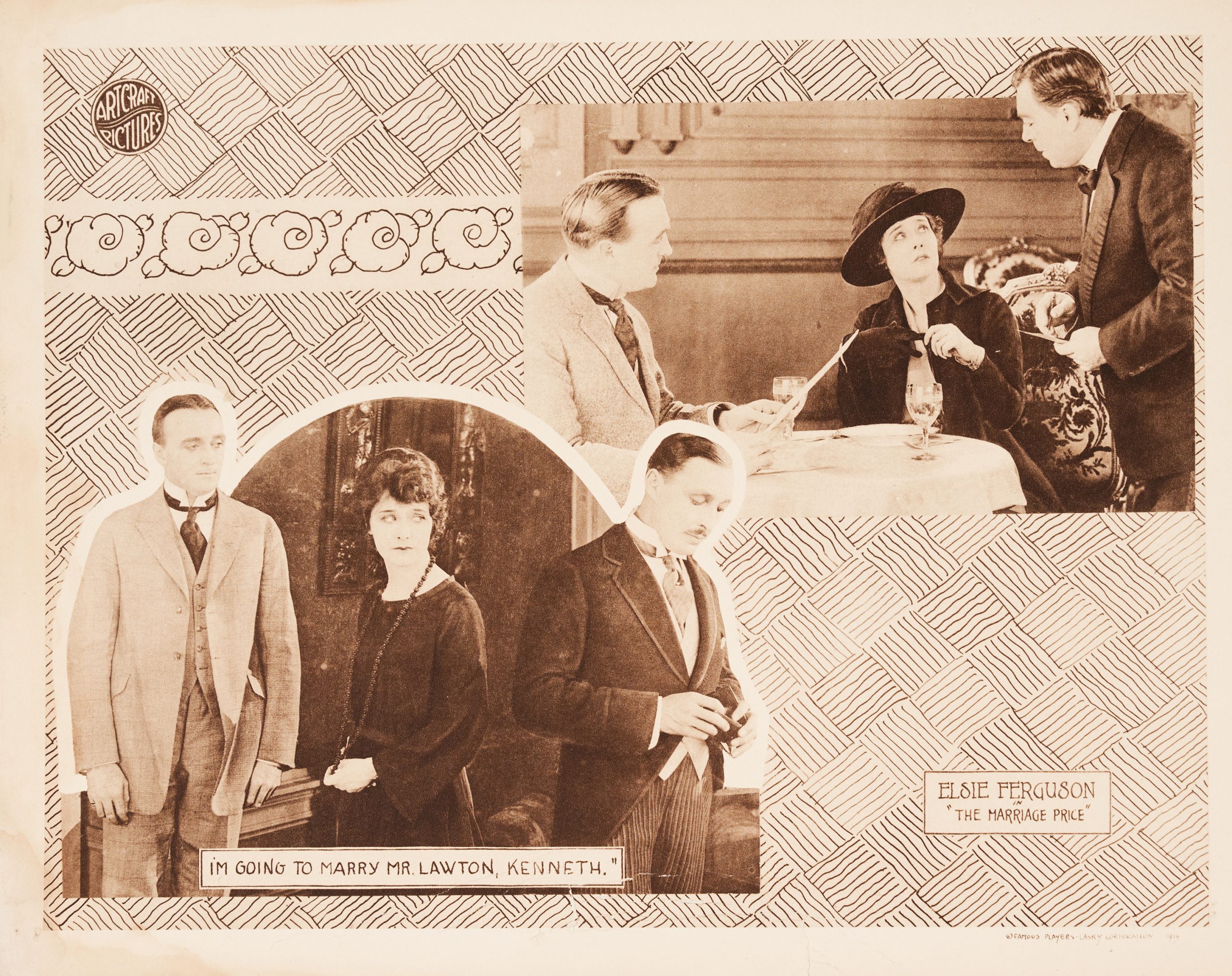

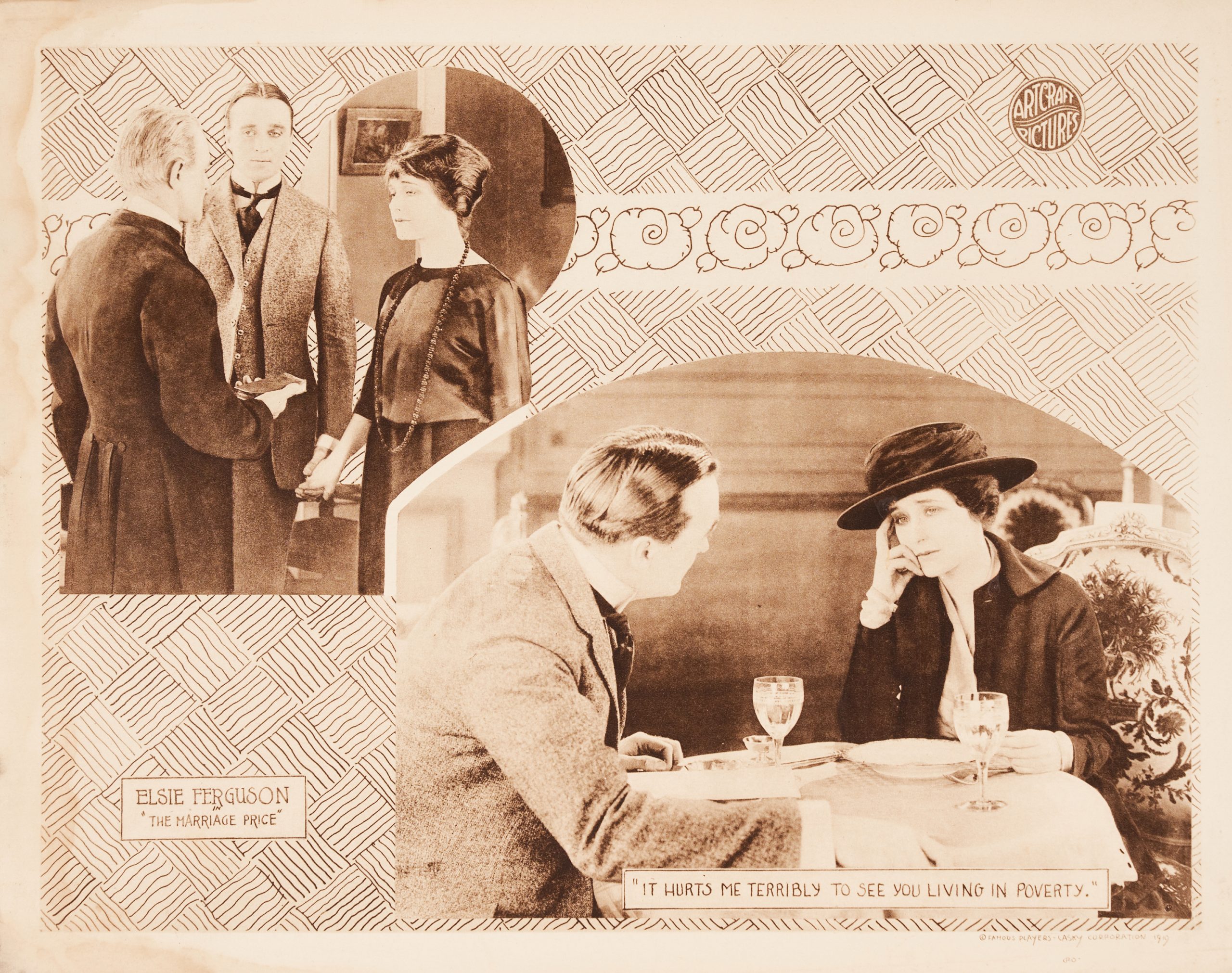

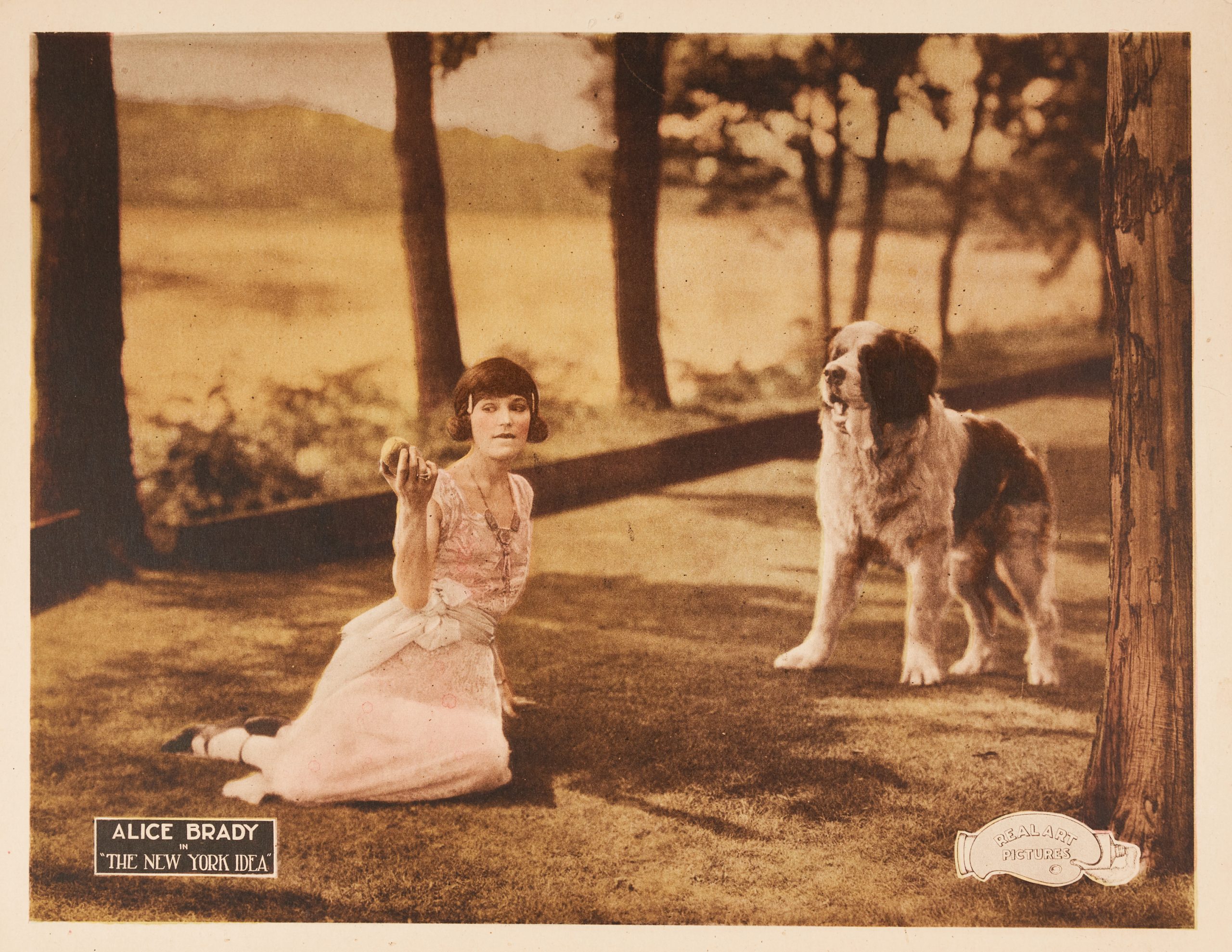

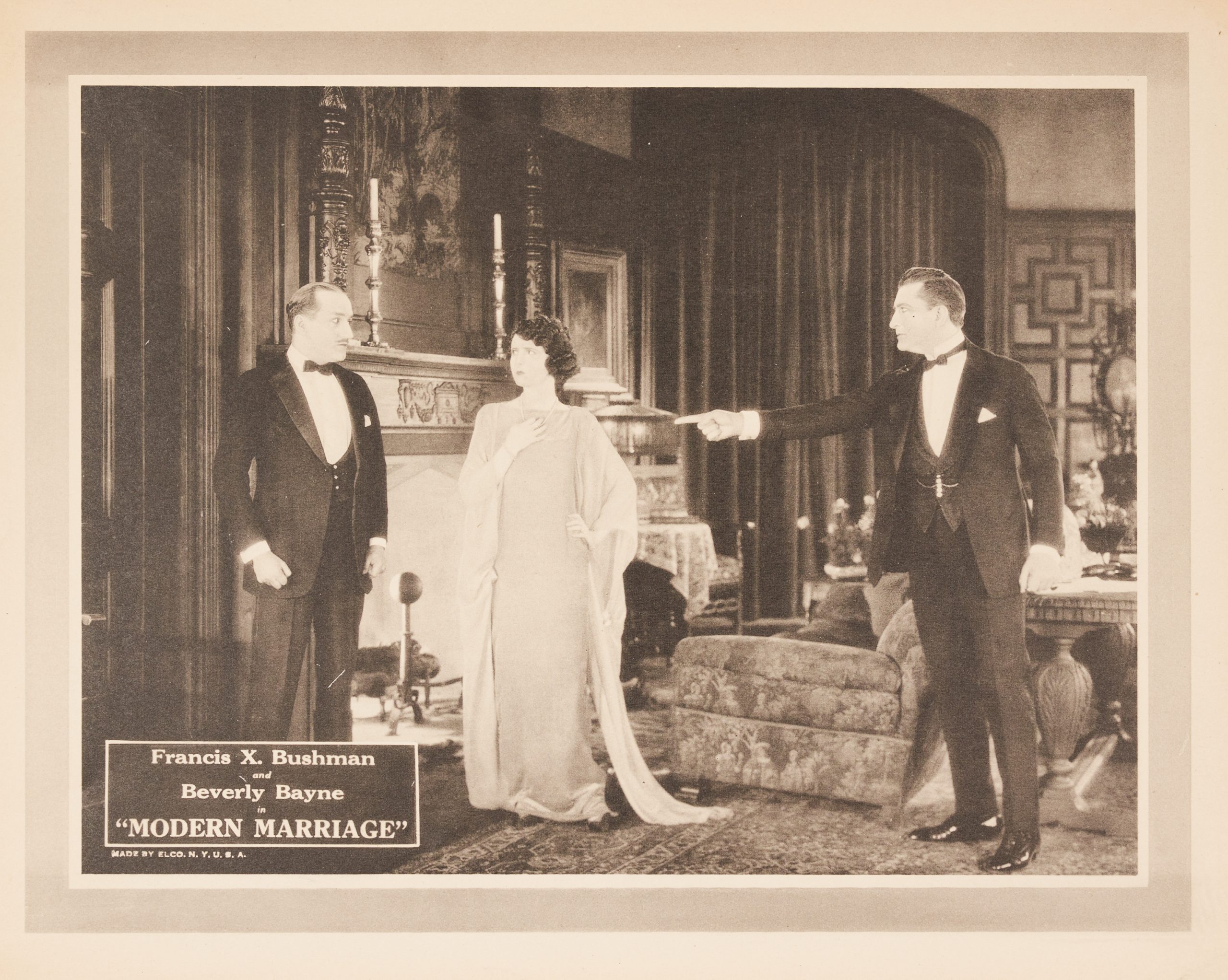

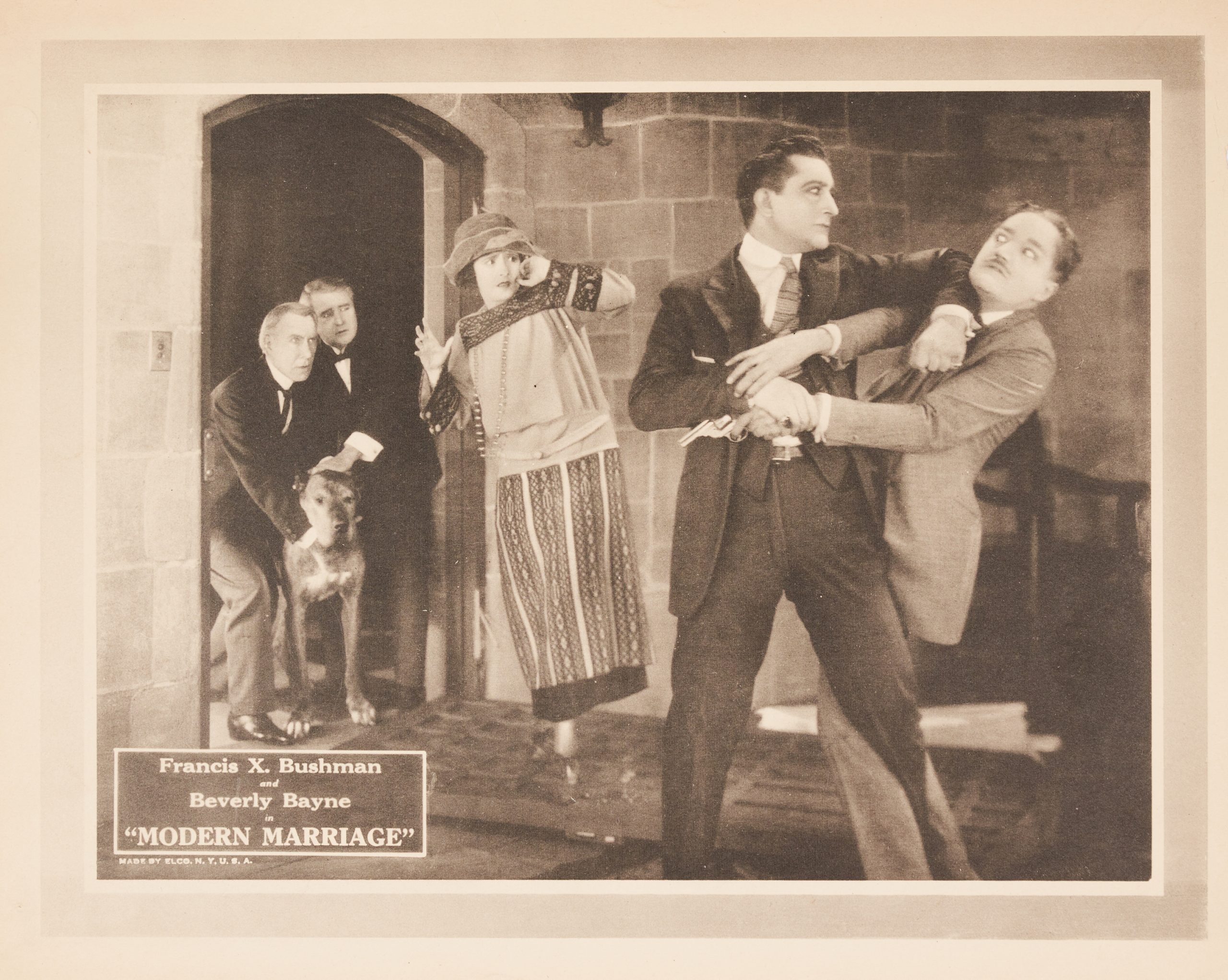

This exhibition focuses on lobby cards advertising Hollywood and East Coast movies made largely by women for women. Typically issued in series of eight, lobby cards functioned as static trailers, showcasing key scenes within a film in order to highlight the plot and lead characters. As their name suggests, they were often displayed in the lobbies of theaters, enticing viewers to come back and see the next film. The particular movies advertised here cover three main topics: women with agency, women who work, and marriage or divorce (or both). Each story was either written, directed, produced, art-directed, edited, or had costumes designed by a woman, and would have been promoted to a predominantly female audience. As roughly 75 percent of early American silent features have since been lost, the topic of women’s participation and how it was credited or preserved remains a ripe area for scholarship.

This exhibition comes to Poster House through a generous loan from Dwight M. Cleveland.