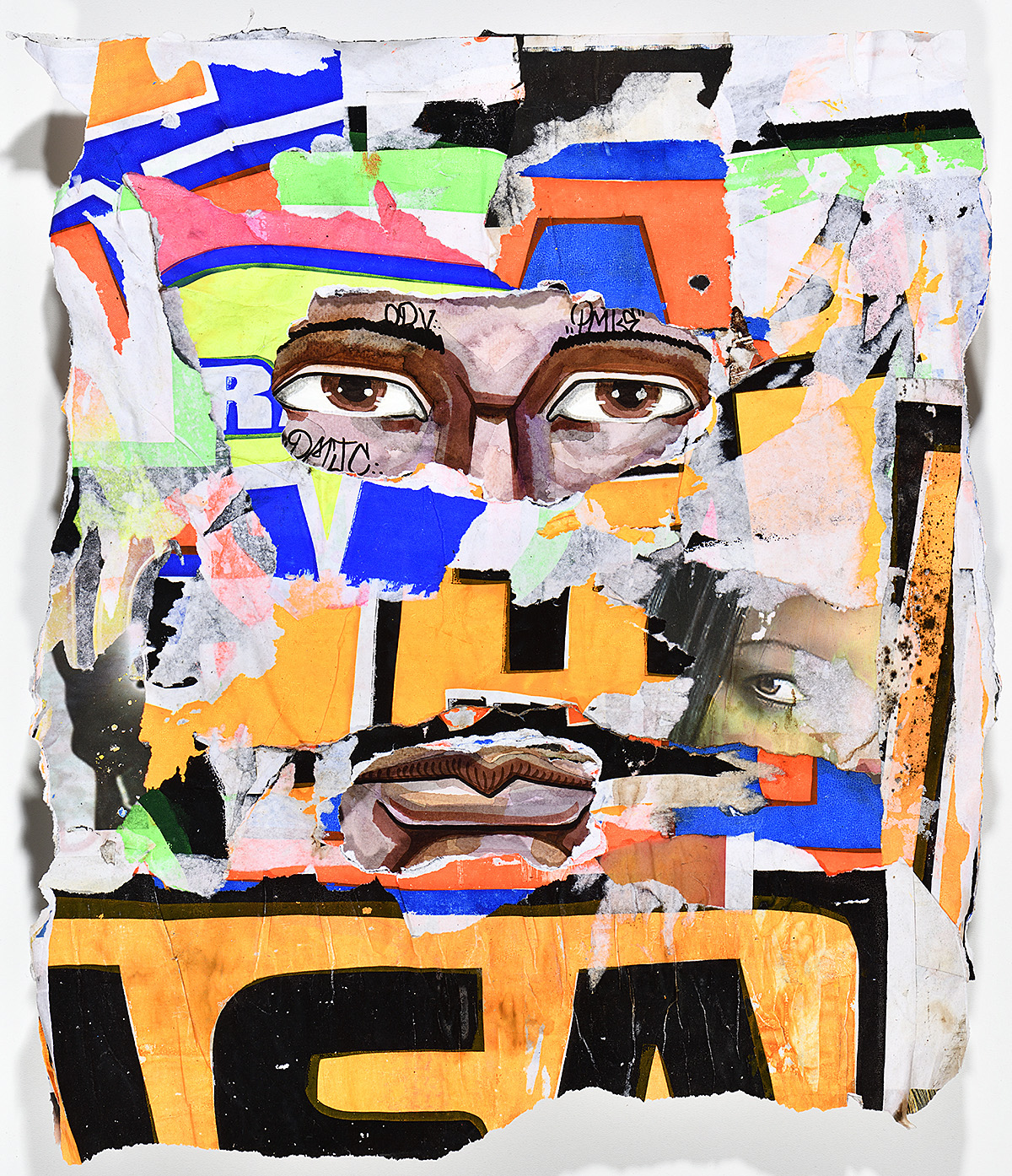

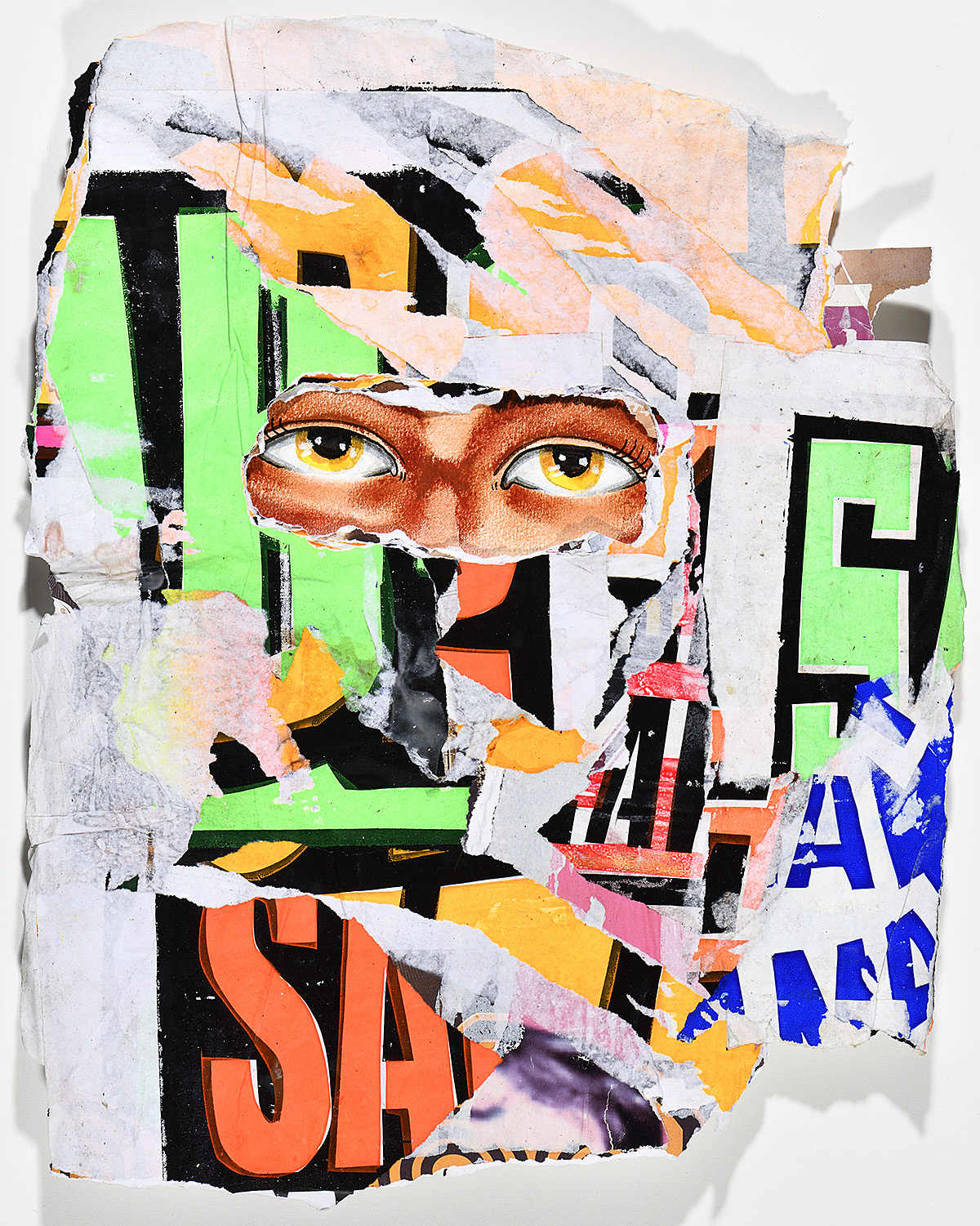

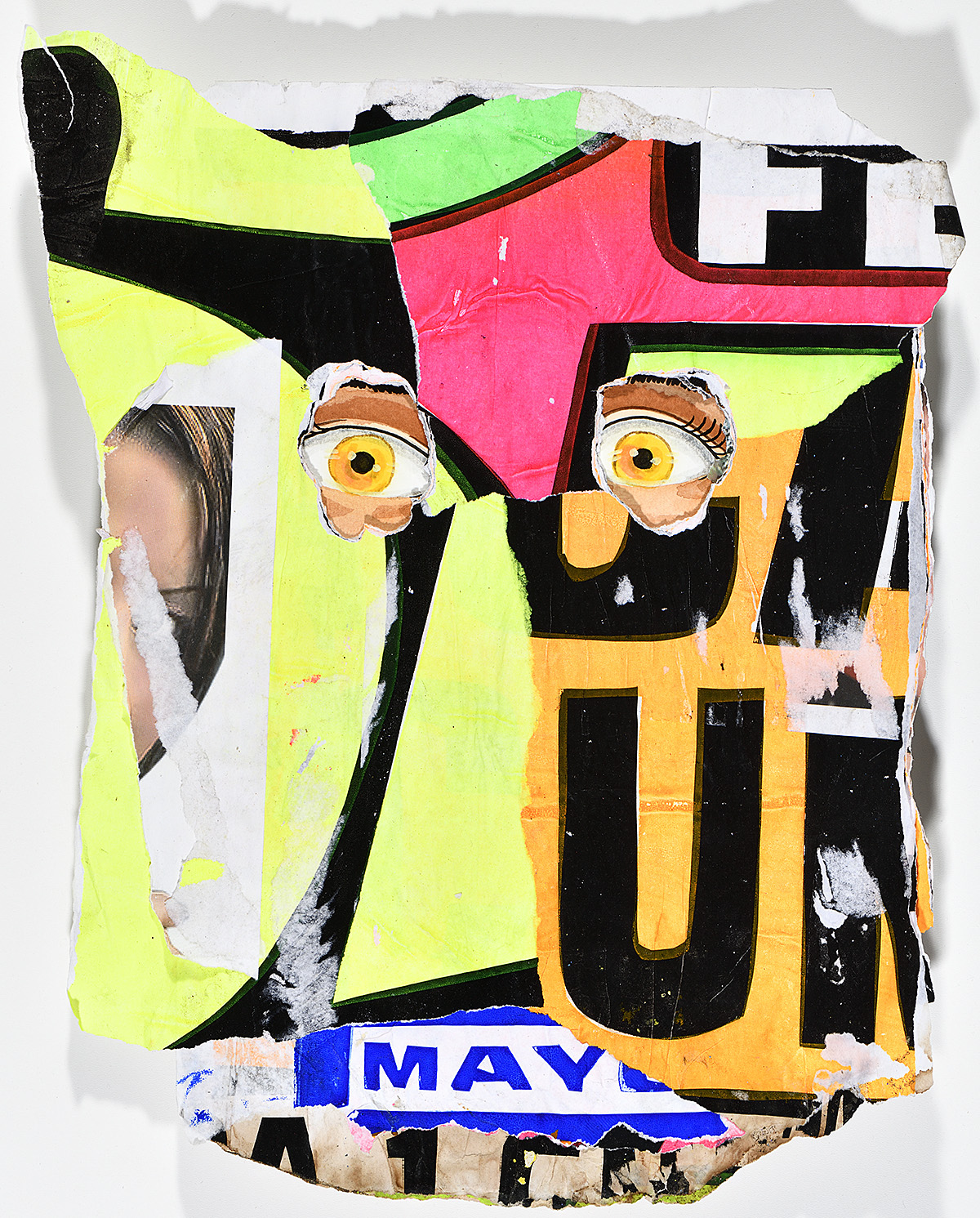

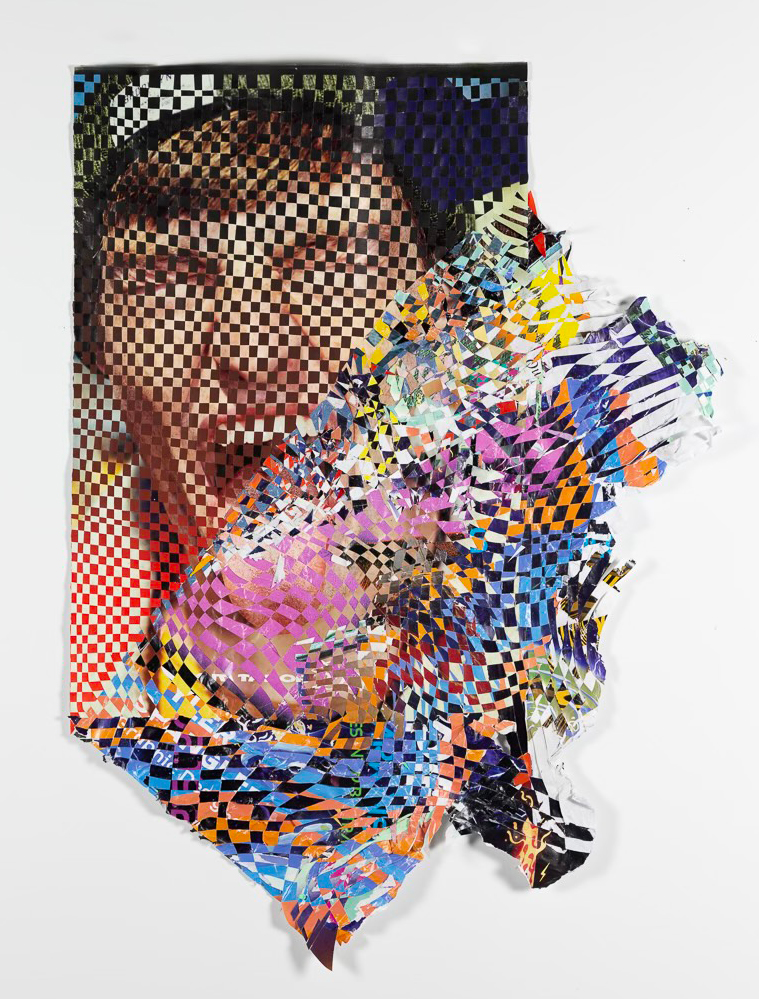

Masked Vigilantes on Silent Motorbikes

“As a private person, I have a passion for landscape, and I have never seen one improved by a billboard…When I retire from Madison Avenue, I am going to start a secret society of masked vigilantes who will travel around the world on silent motor bicycles, chopping down posters at the dark of the moon. How many juries will convict us when we are caught in these acts of beneficent citizenship?”—David Ogilvy, advertising executive, 1963

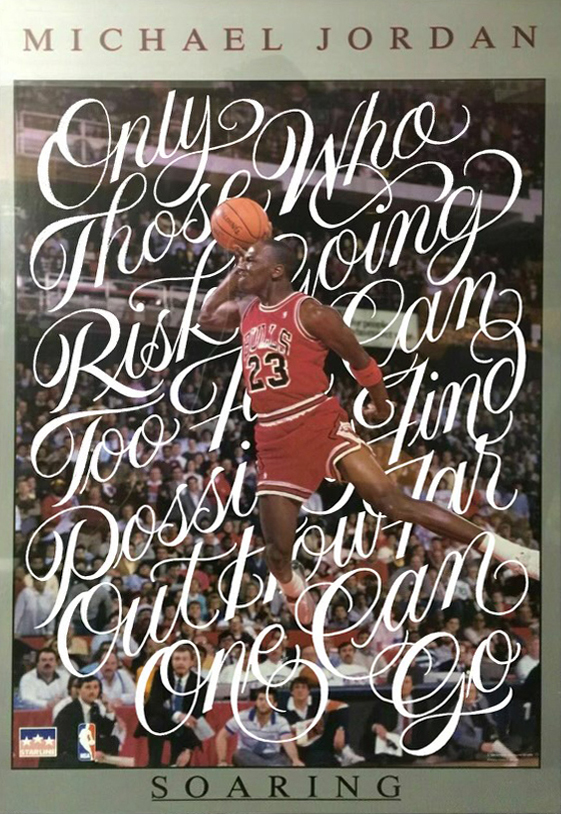

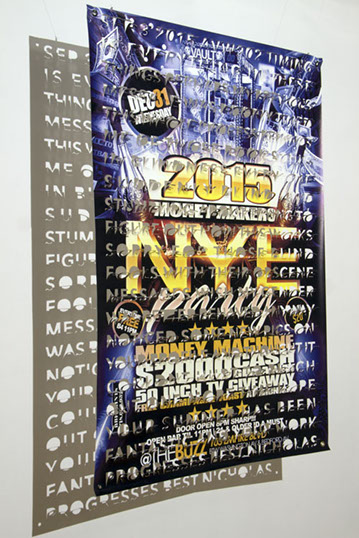

Posters both reflect and shape popular culture. They are put on the street with a simple goal: to occupy the public imagination. A designer can influence culture on a global level with a single compelling image. Posters are also accessible vehicles for everyone from the largest corporations to underground nightlife promoters. Their ubiquity and eye-catching imagery have made posters cultural touchstones with meanings that extend far beyond the products and events they are intended to showcase. Memorable World War I posters, for example, propelled the 19th-century figure of Uncle Sam, the personification of the federal government, and Santa Clause, shown with troops and selling war bonds, into symbols of American patriotism. Movie posters spawn internet memes, gig posters inspire fashion trends, and political posters immortalize the rallying cries that elect presidents or take down governments. Posters are powerful.

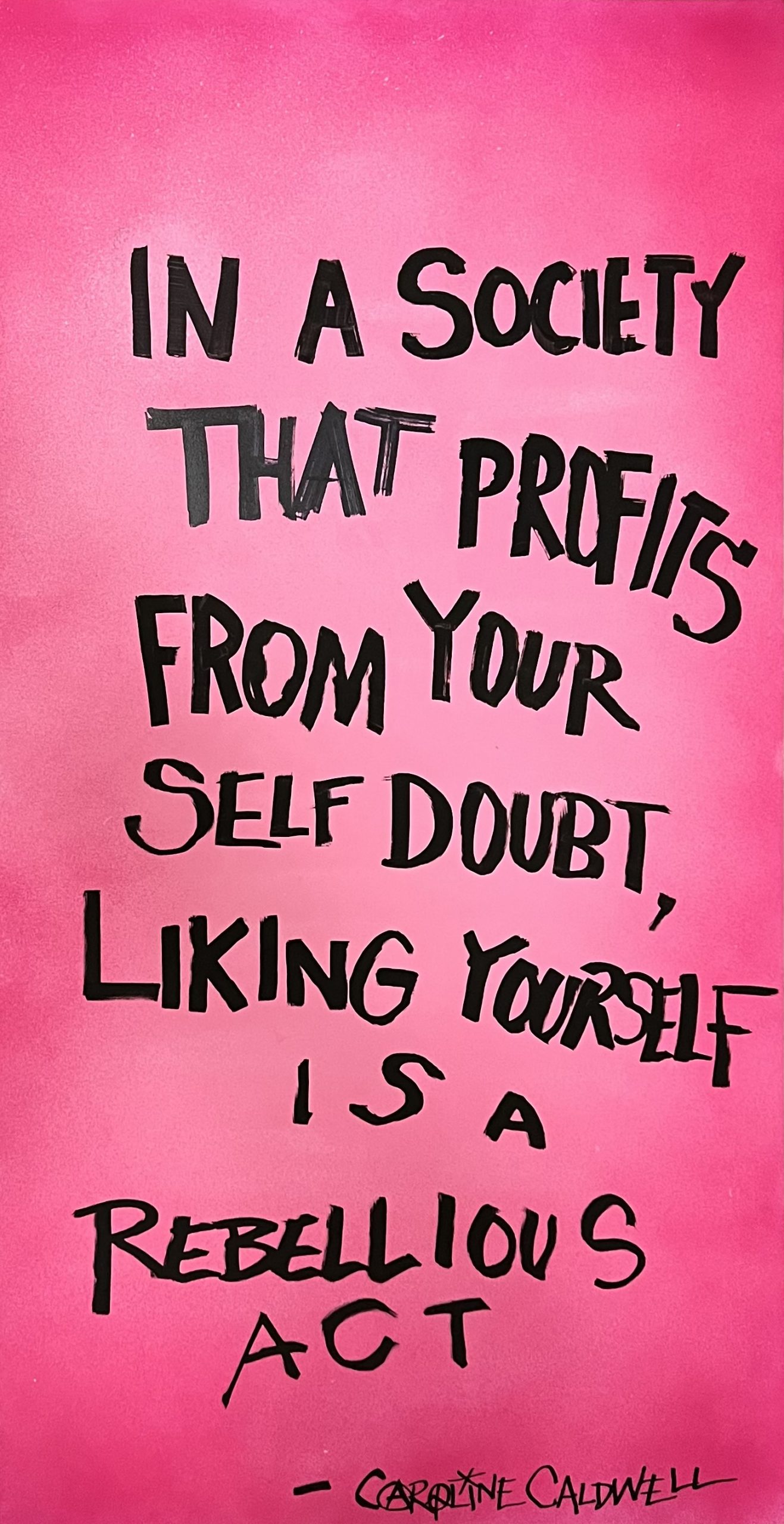

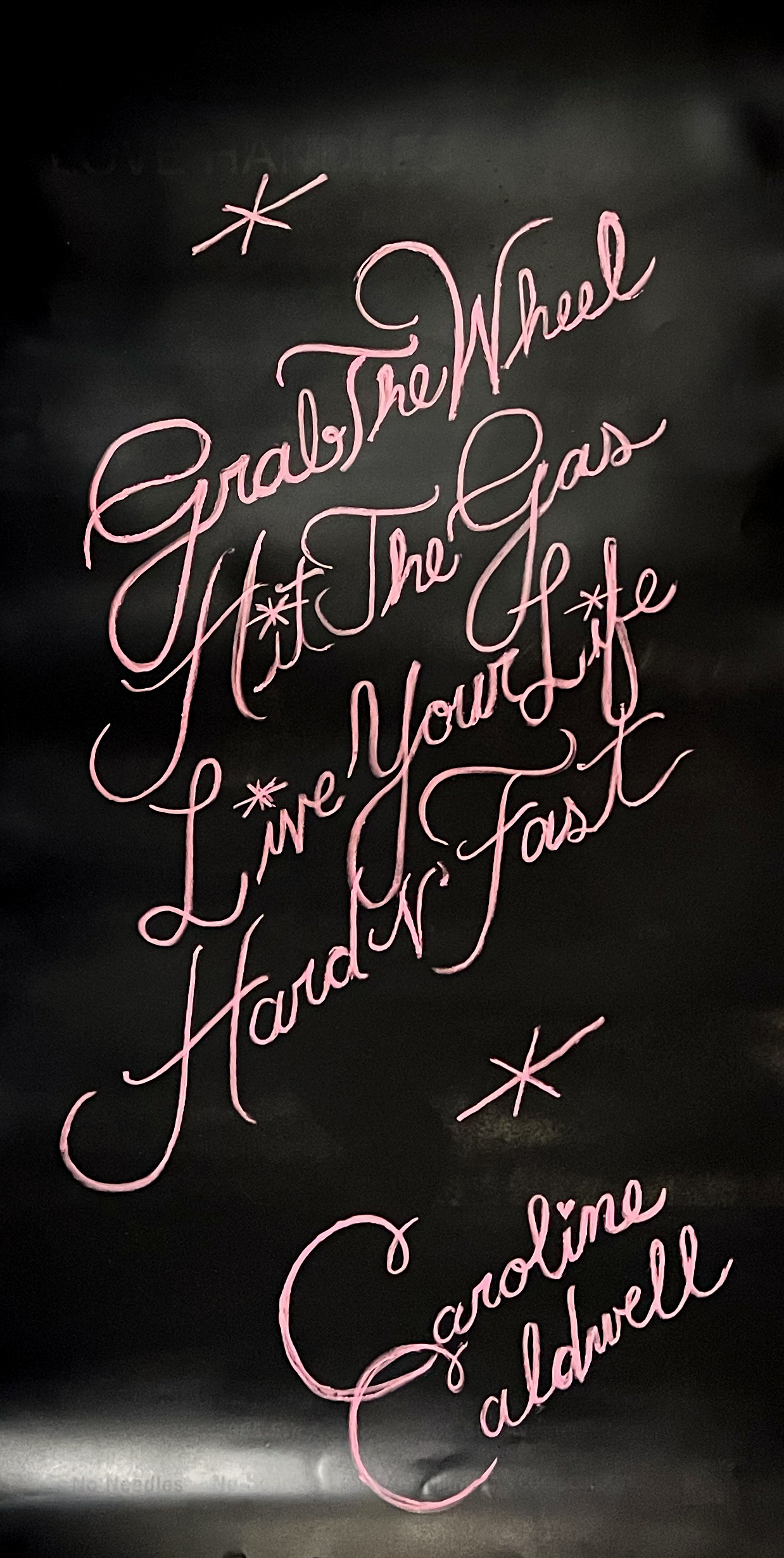

Critics, however, have long compared commercial messages in public spaces to visual pollution. In 1887, one London commentator described walls of street posters as “vast vistas of vulgarity.” Although some of the early criticisms of posters look decidedly like conservative resistance to sexually suggestive messages, there have also been concerns about the impact of posters on viewers and their role in the aggressive promotion of capitalism. More recently, organizations like the World Wildlife Fund and UNICEF have condemned the advertising industry for subjecting adults and children to a range of health and social risks related to overconsumption, poor nutrition, and the promotion of materialism. And yet, from bus shelters to private billboards to posters outside construction sites, cities are still filled with large sheets of paper instructing passersby on what to buy, how to think, and what to do.

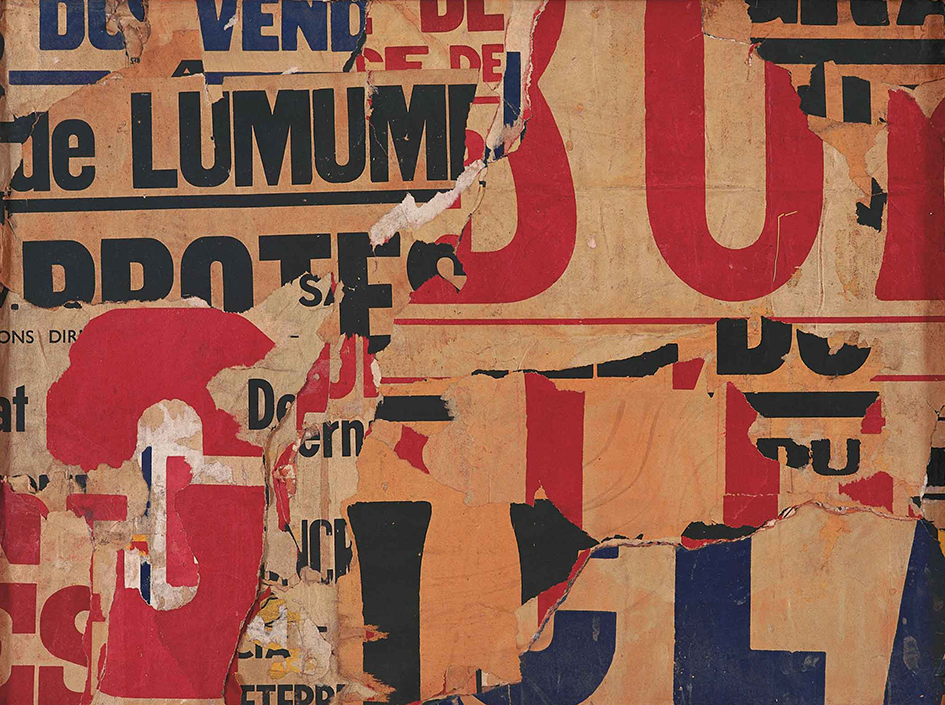

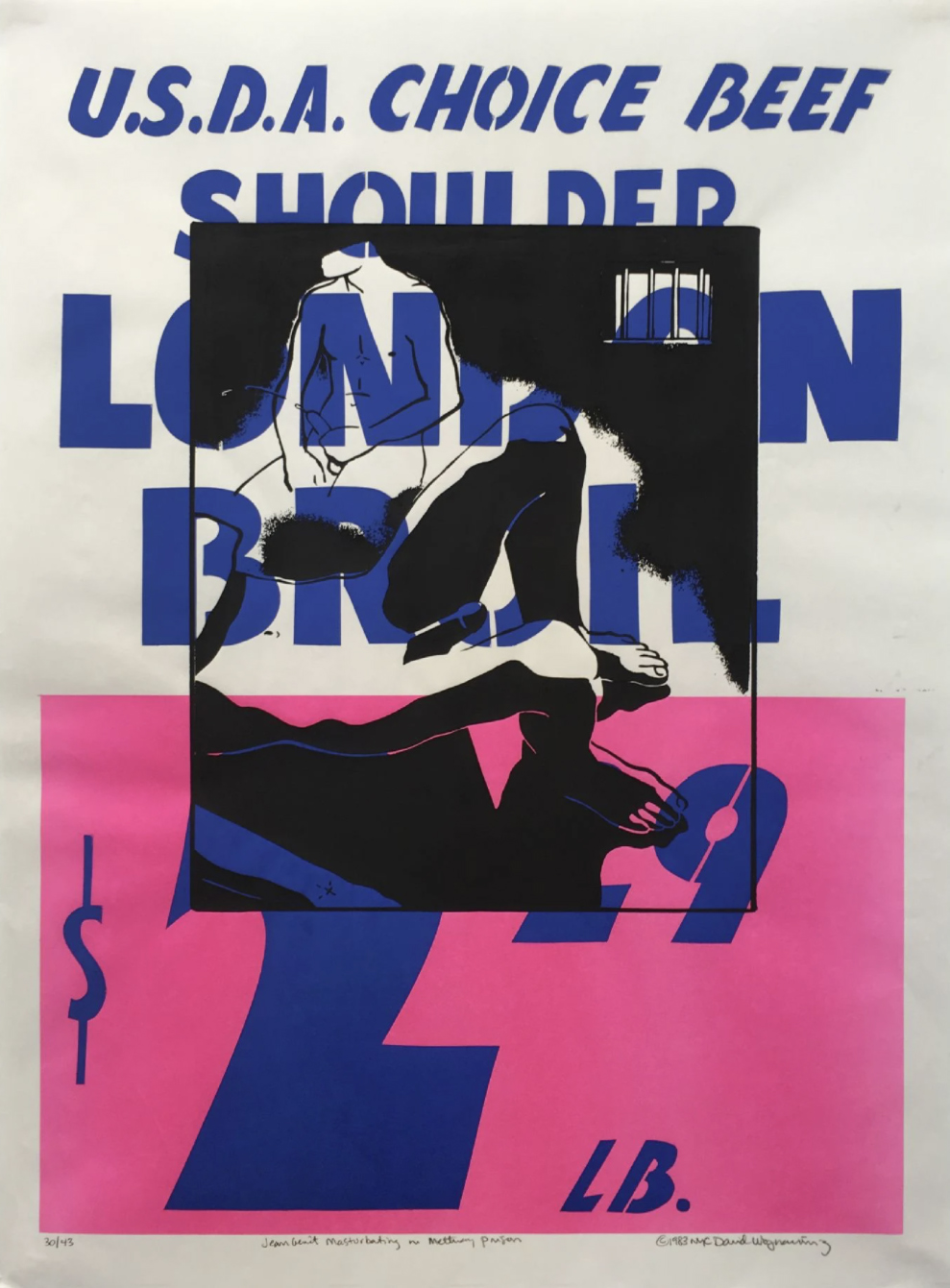

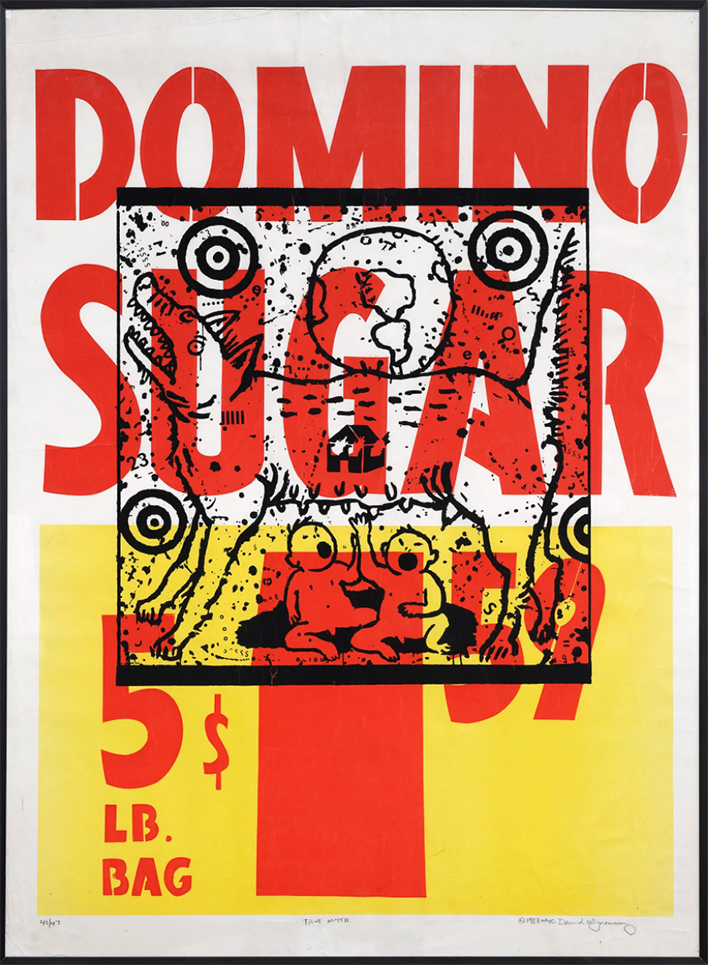

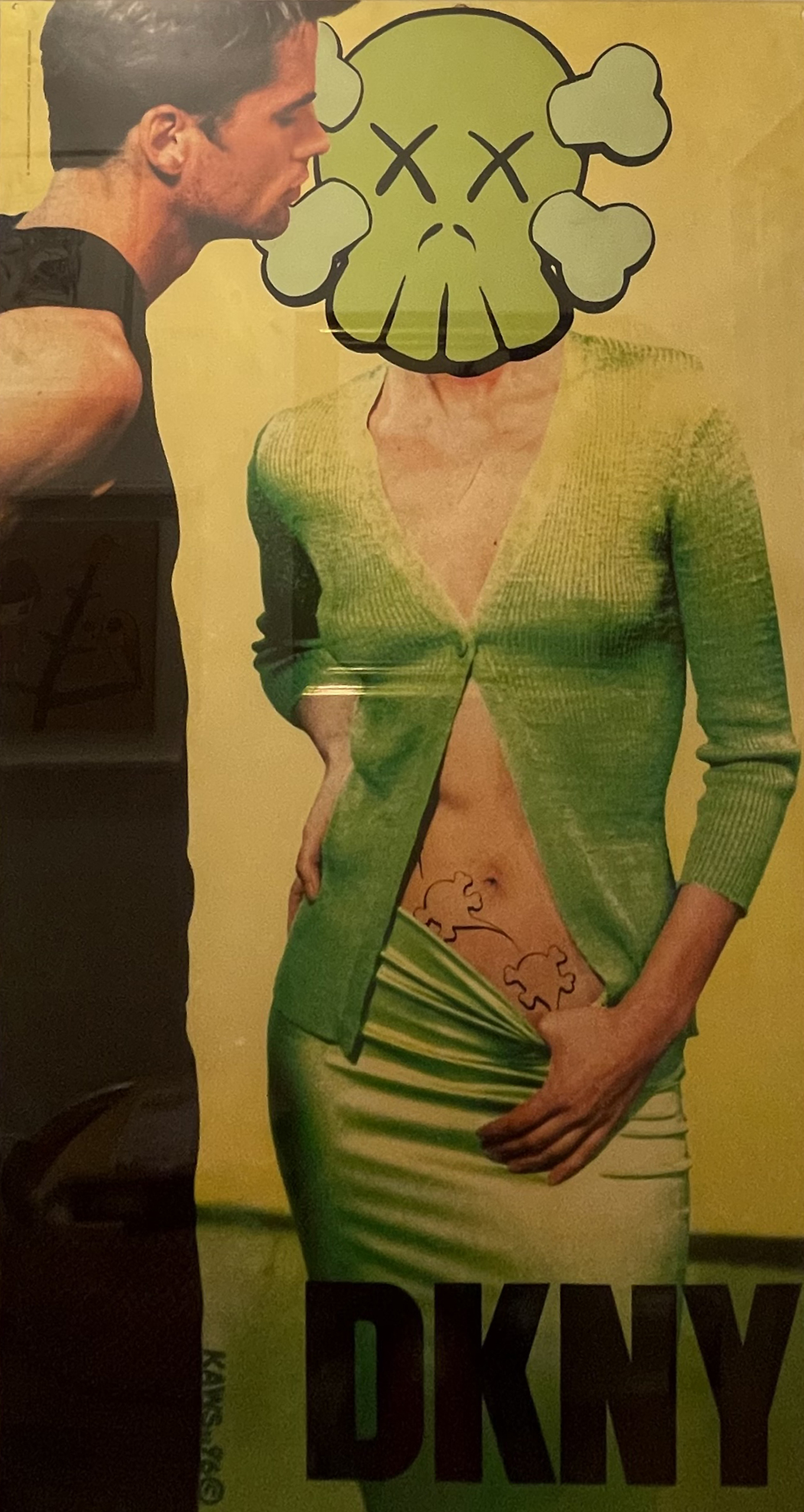

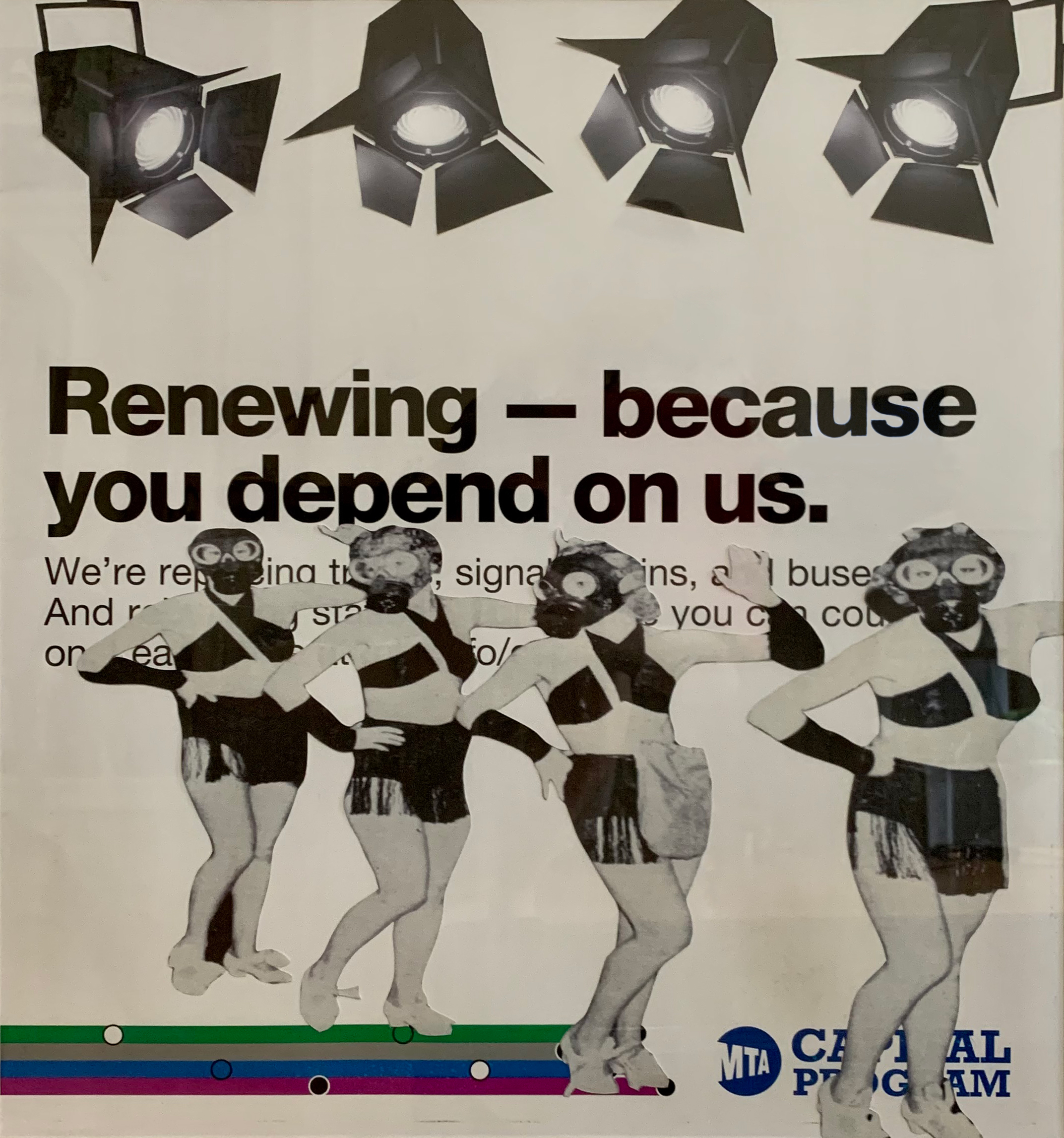

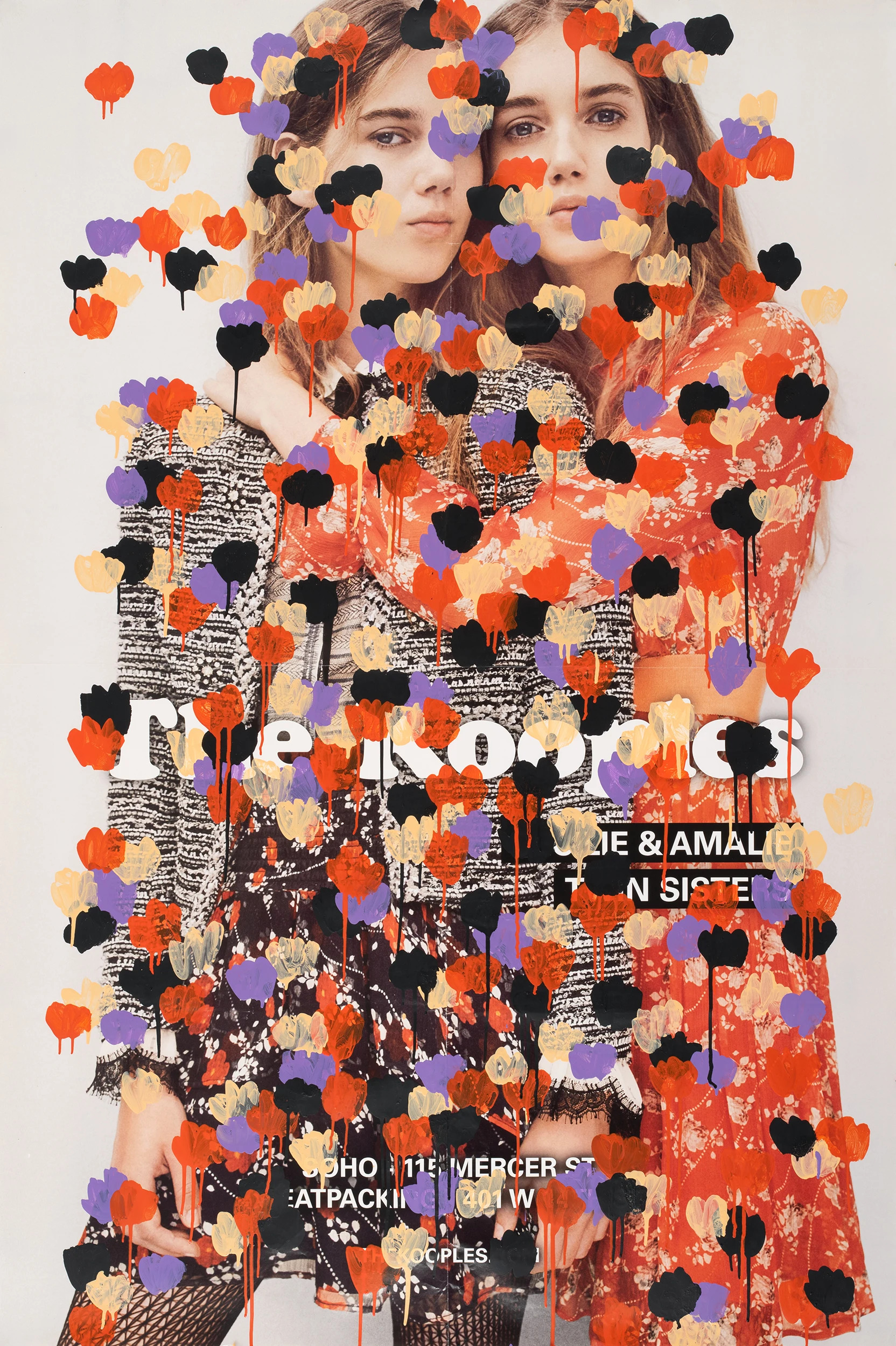

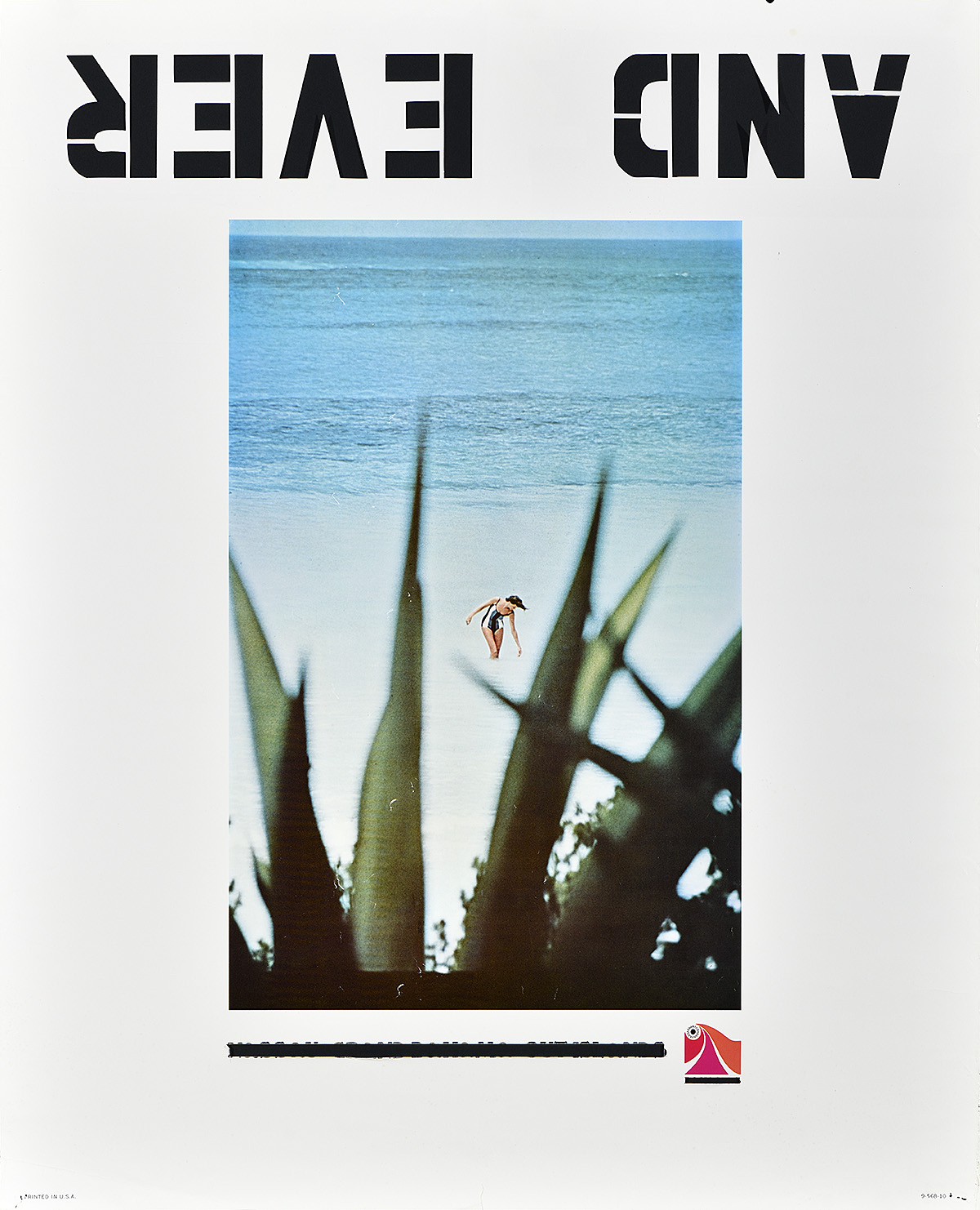

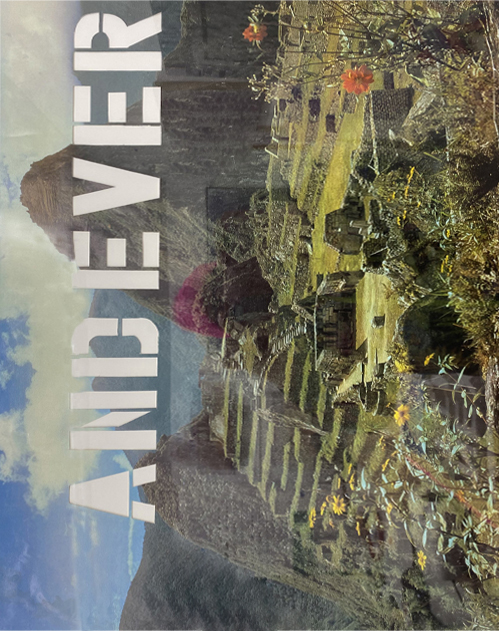

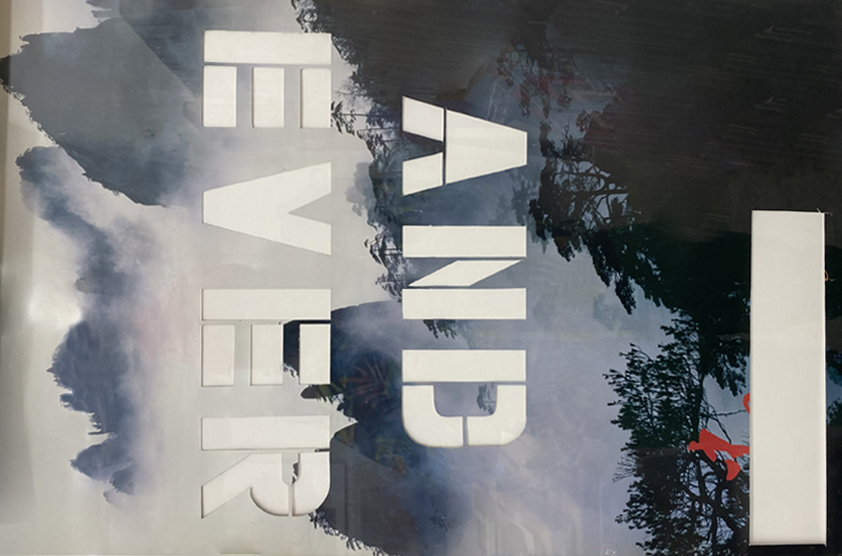

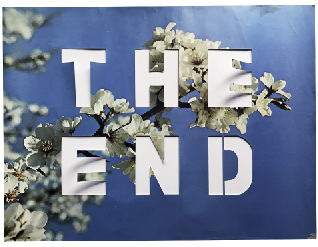

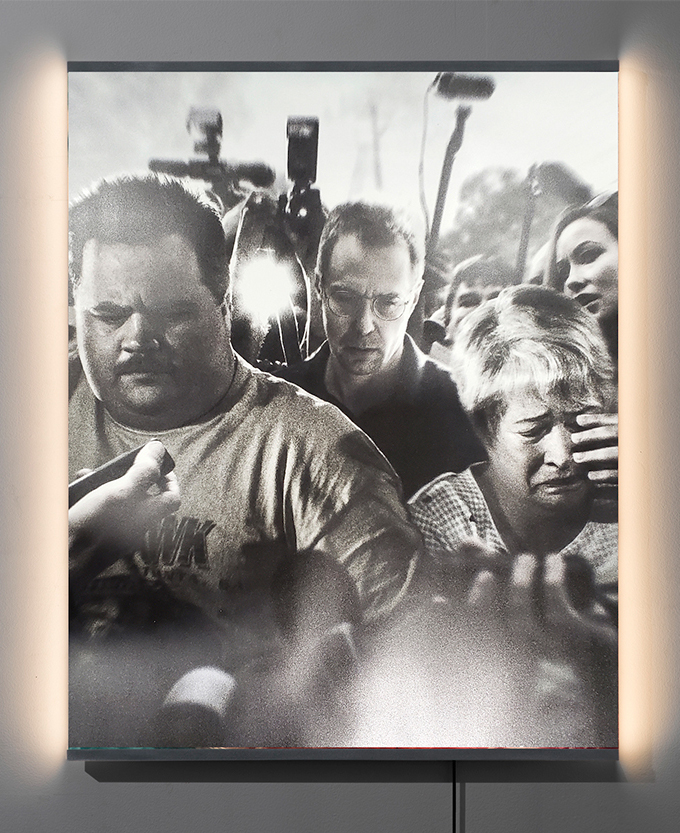

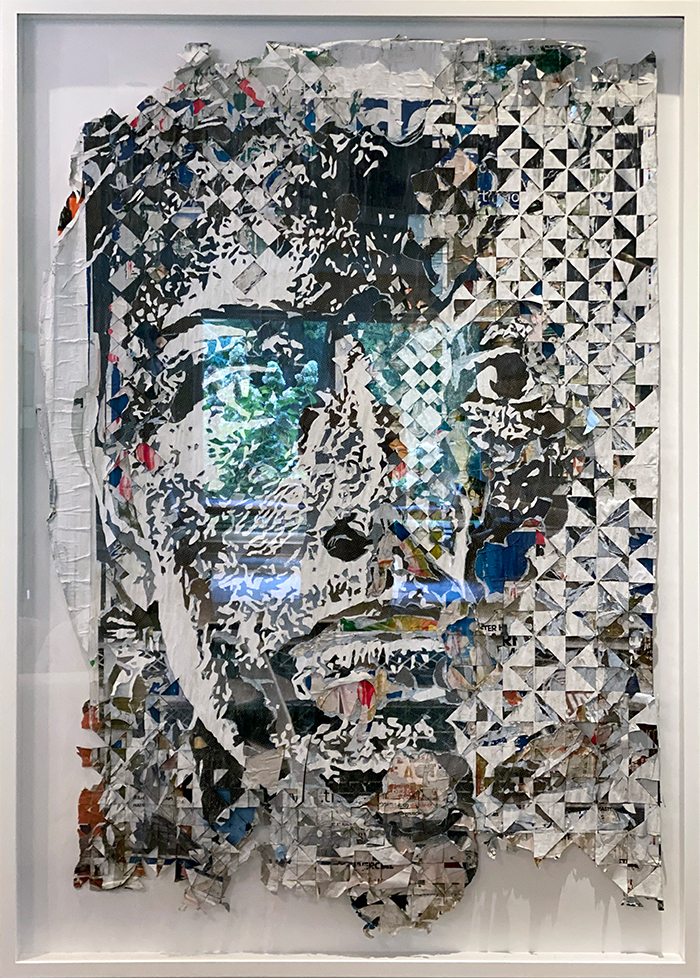

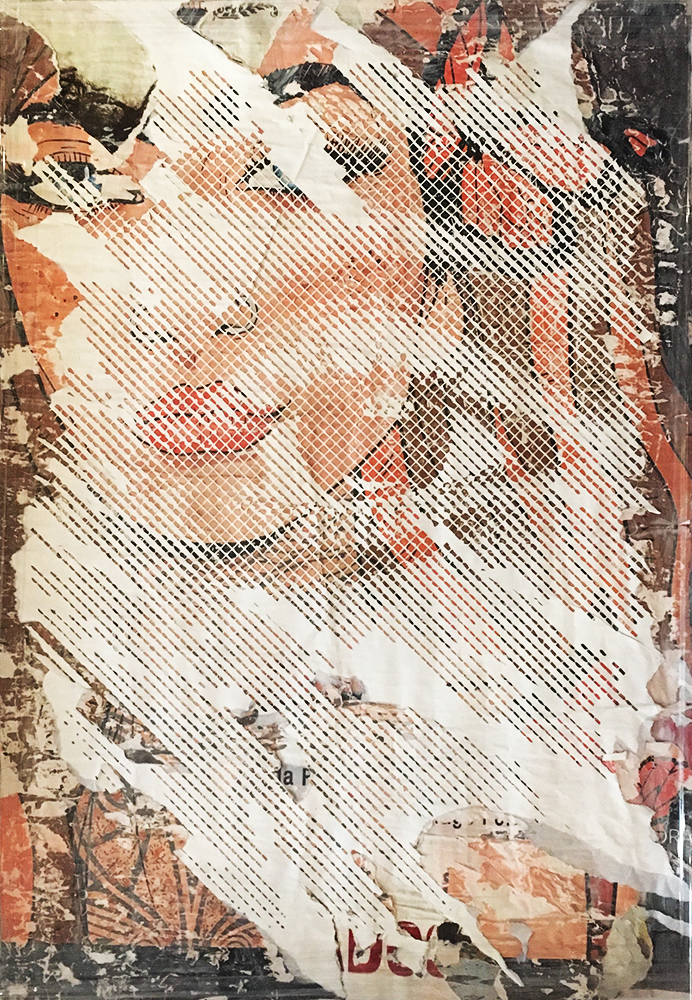

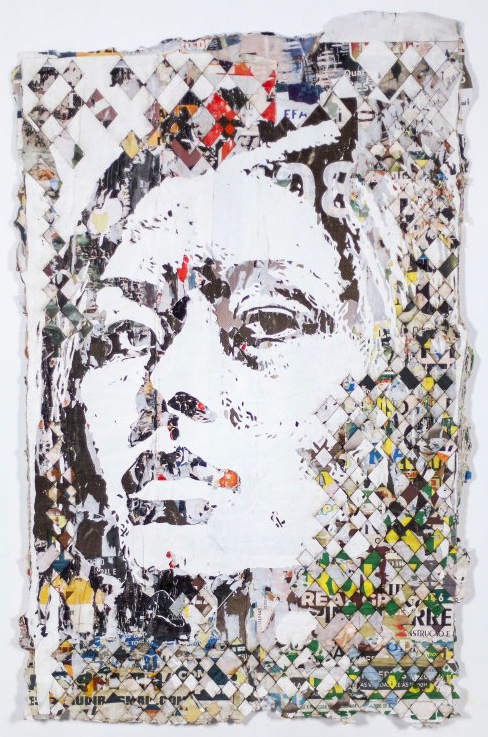

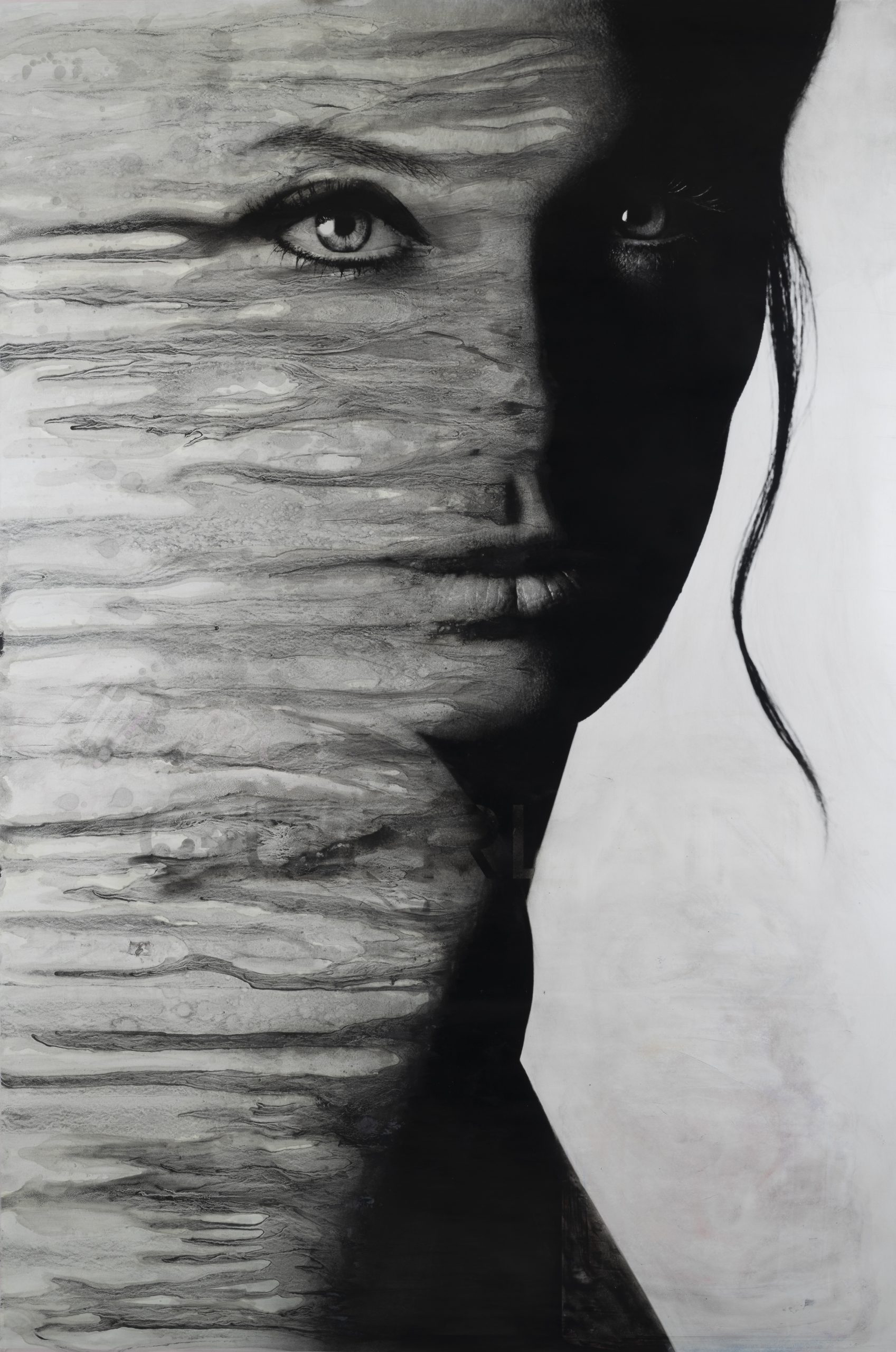

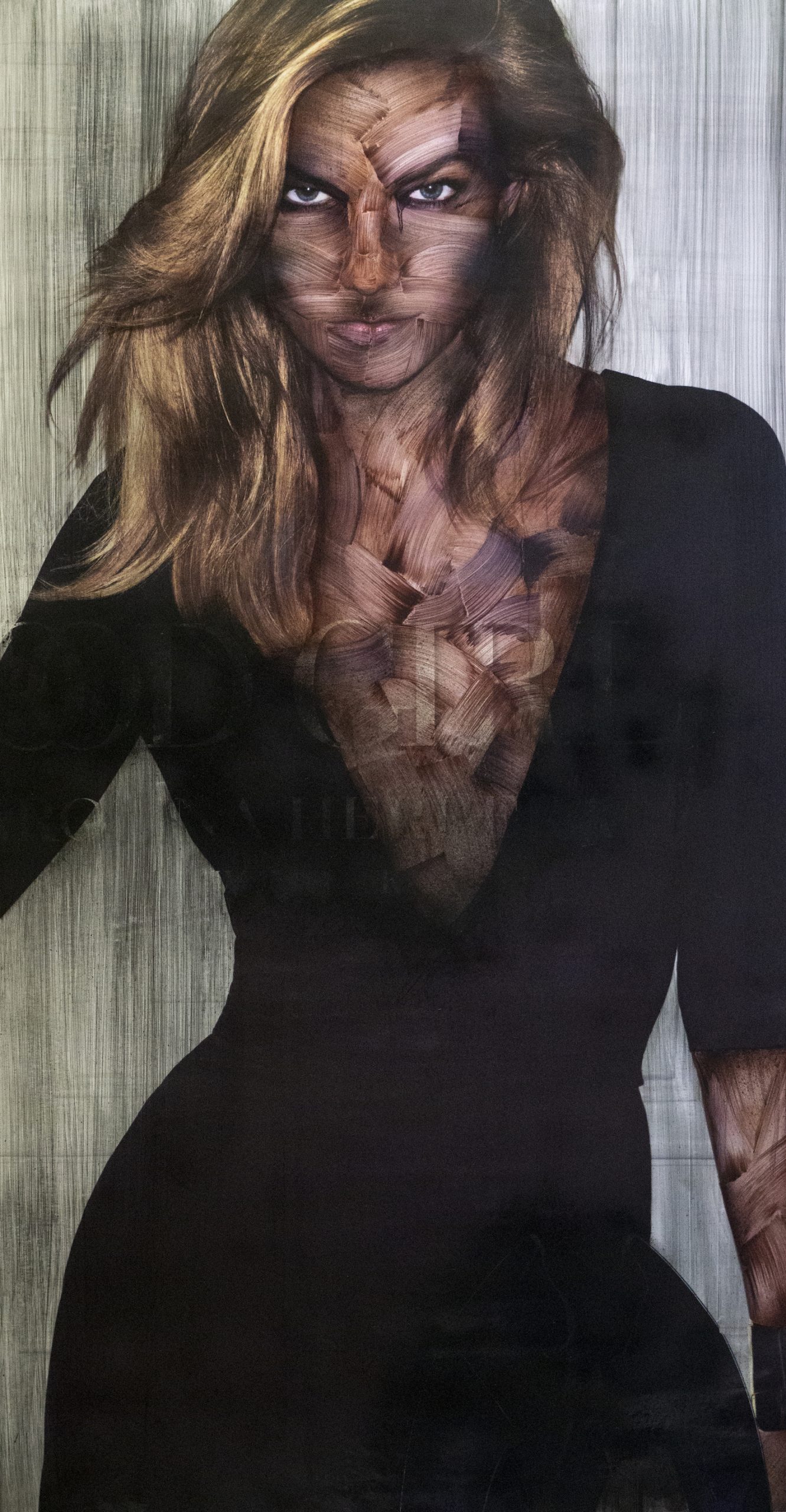

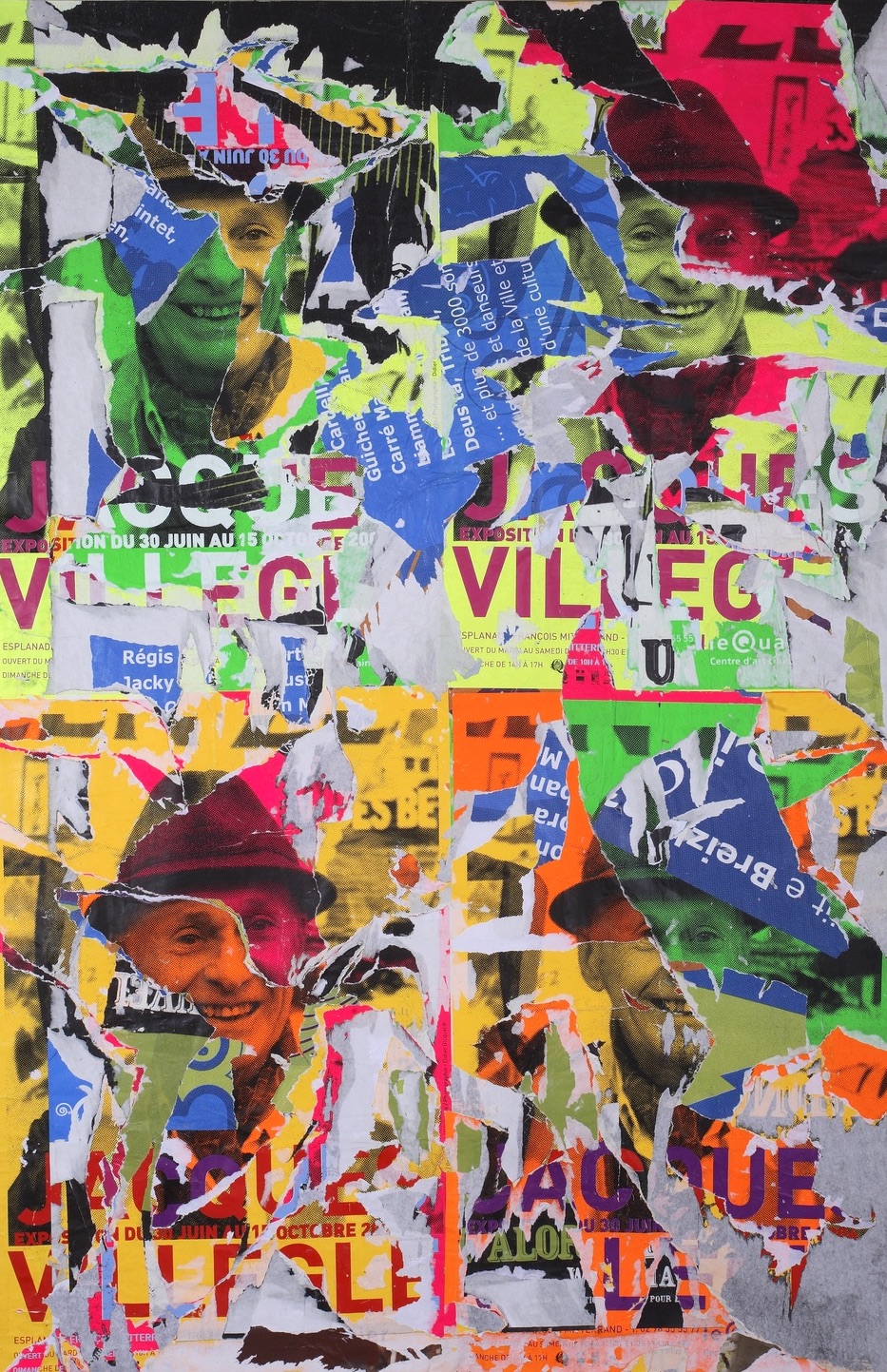

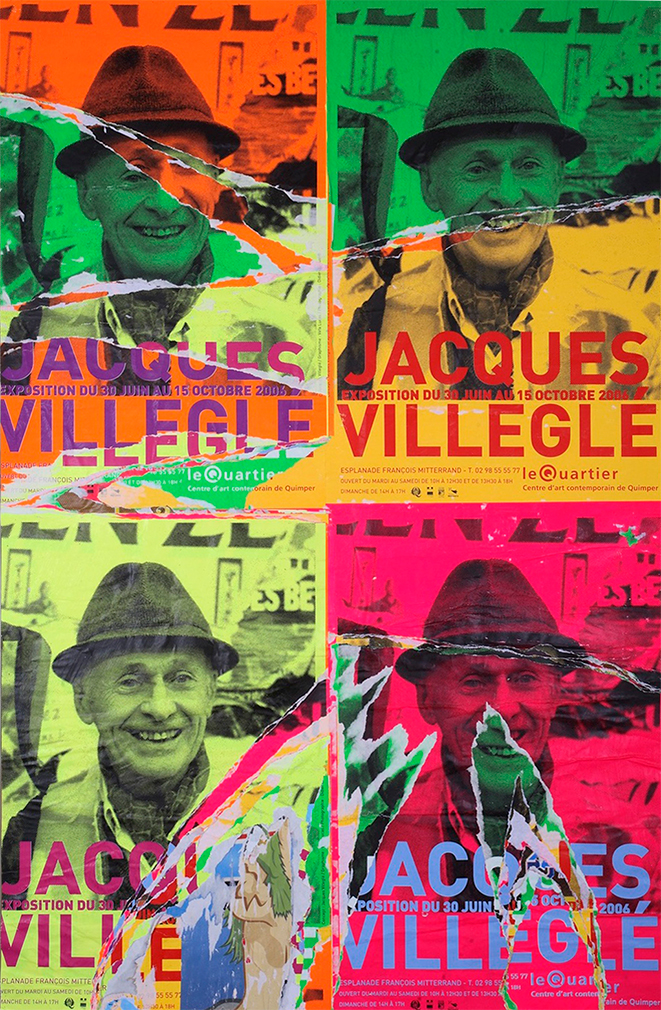

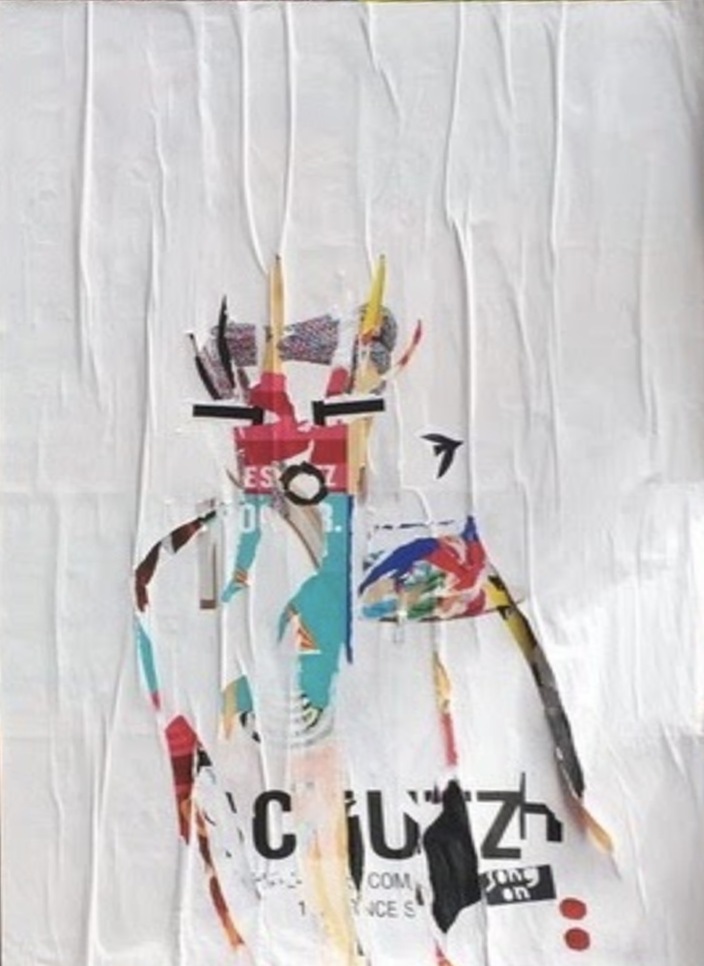

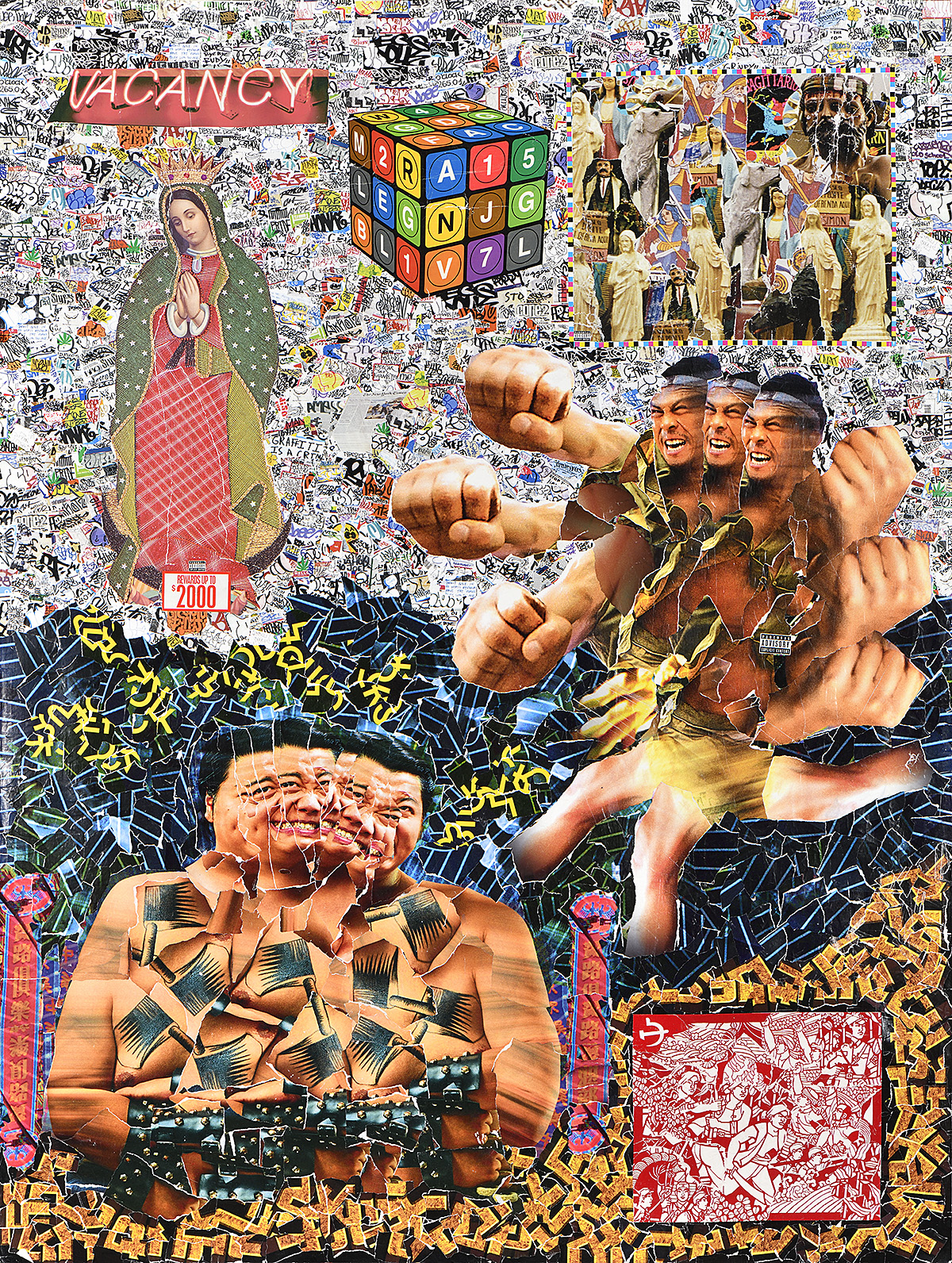

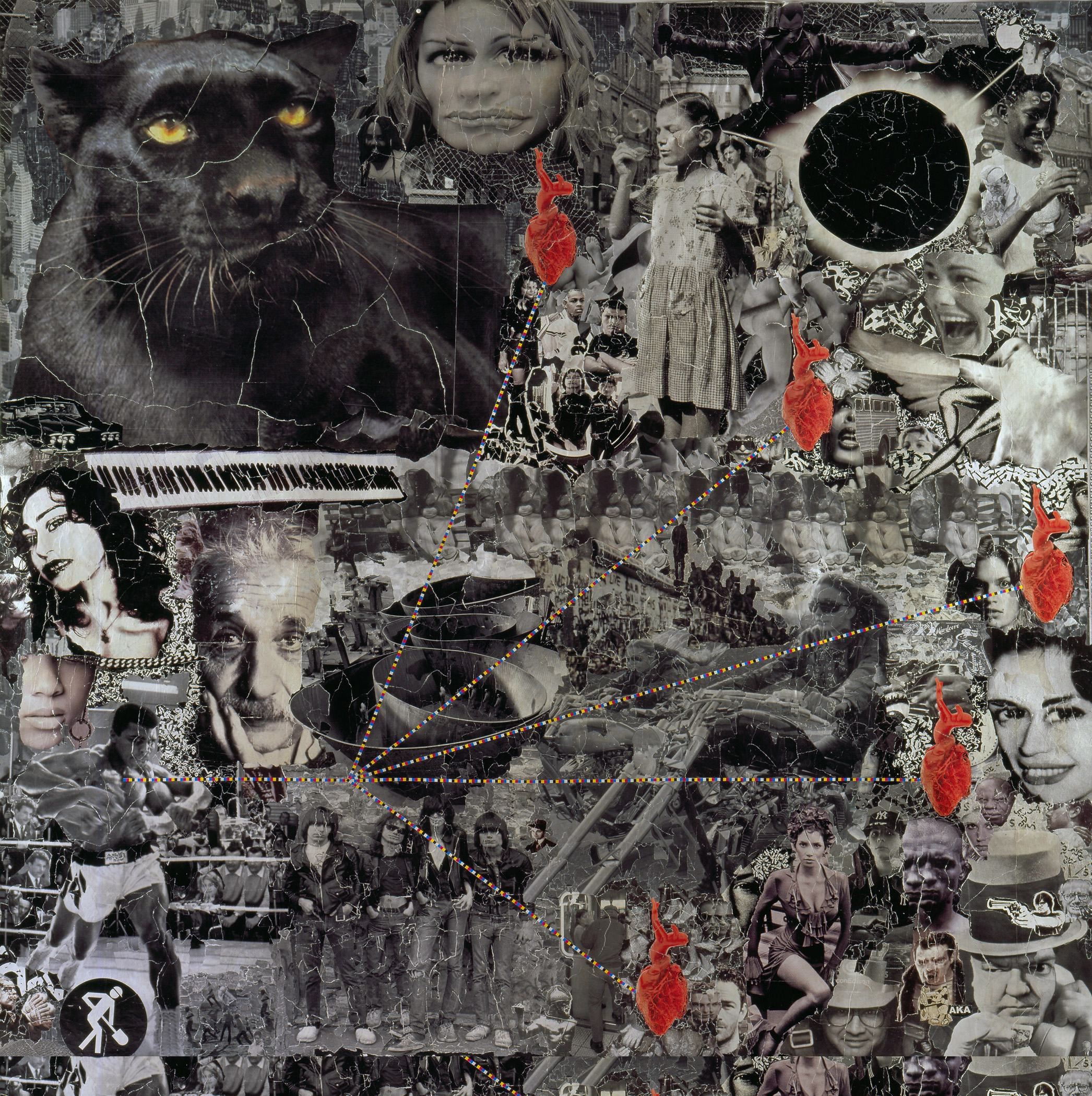

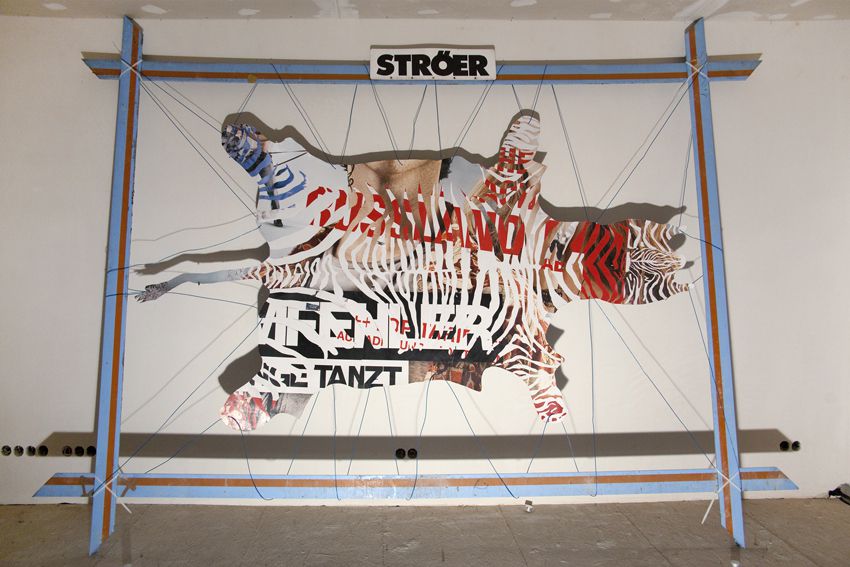

For artists, advertising posters offer easy access to a shared bank of pop-cultural imagery and to the collective imagination. This approach is rooted in the concepts and techniques of French avant-garde artists of the 1950s and ’60s, including the Situationists, the Nouveau Réalistes, and other groups that encouraged artists to recontextualize materials from mass culture to say something new. Their methods, ranging from décollage (literally to “unstick,” used in this context to refer to the making of art from posters torn from walls) to détournement (meaning the “rerouting” or “appropriation” of popular imagery in a new artwork that represents its antithesis), were intended as tools of collective cultural construction. It also relates to the work of postwar American artists, some of whom, like Robert Rauschenberg, applied found objects and printed ephemera to their paintings, and to the Pop art of Andy Warhol and others, which incorporated everyday commercial images. By reconfiguring scraps of posters into works of art, these artists redefined the relationship between brand and audience, criticized or co-opted the powers of capitalism and celebrity, and perforated the line between public and private space.

Masked Vigilantes on Silent Motorbikes is not an exhibition of poster art but of art that uses found, reconfigured, and mutilated posters as the raw material for something new. The posters used in these artworks were, for the most part, salvaged from the street by the artists, not directly supplied by the advertisers or printed with the idea of subsequent artistic intervention.

Please be advised that this exhibition contains graphic sexual content and ableist language.