Black Power to Black People: Branding the Black Panther Party

Introduction

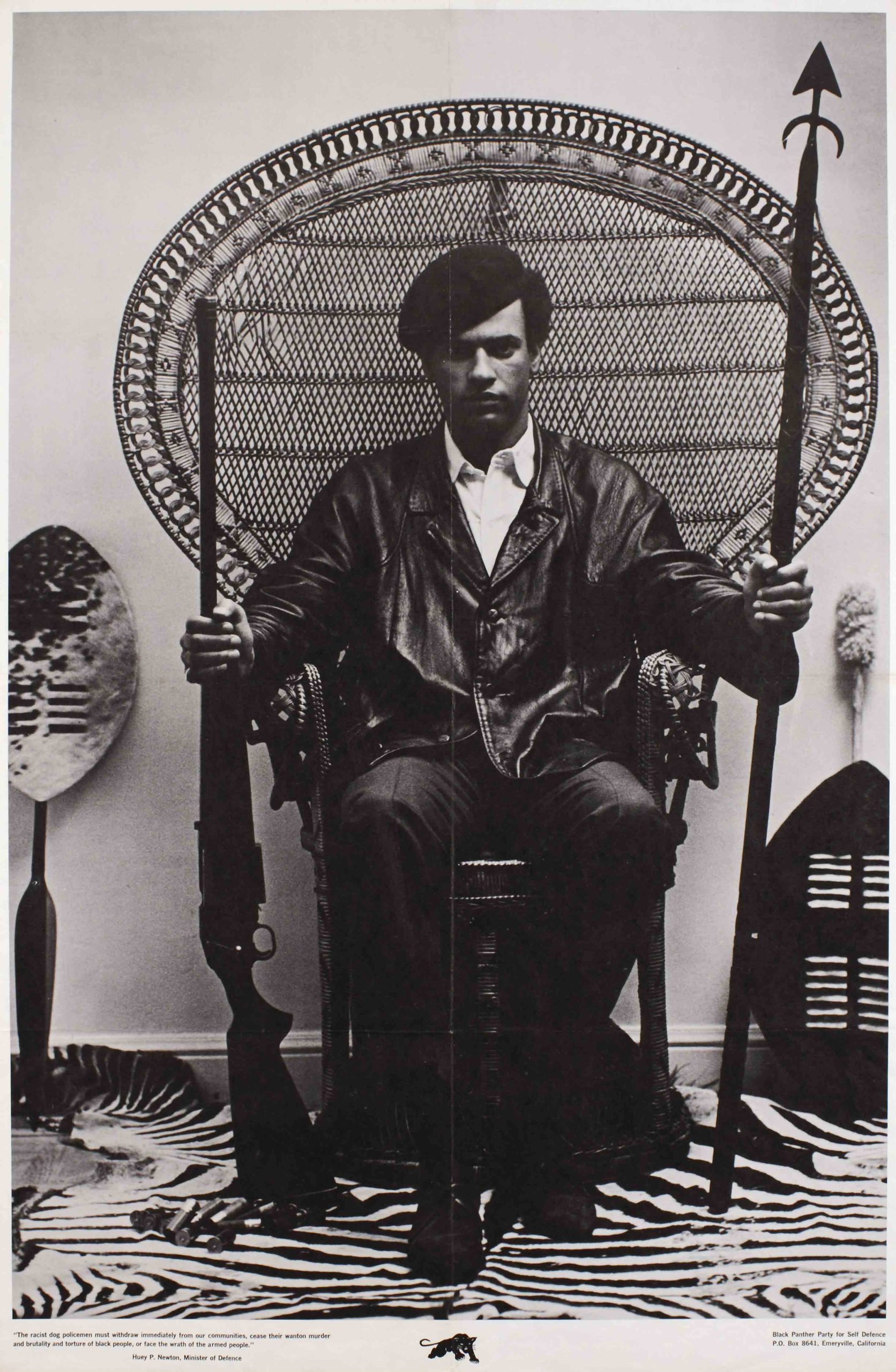

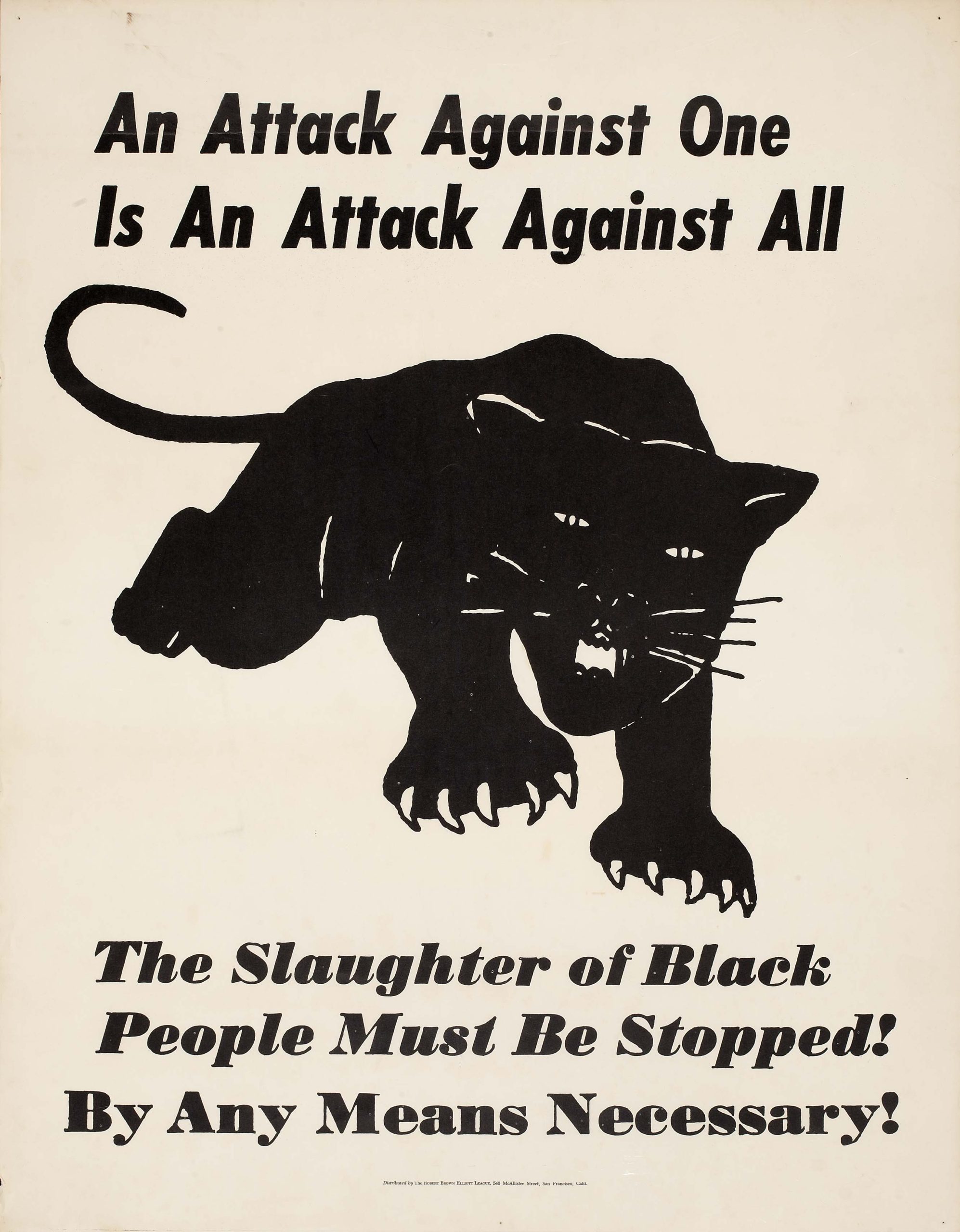

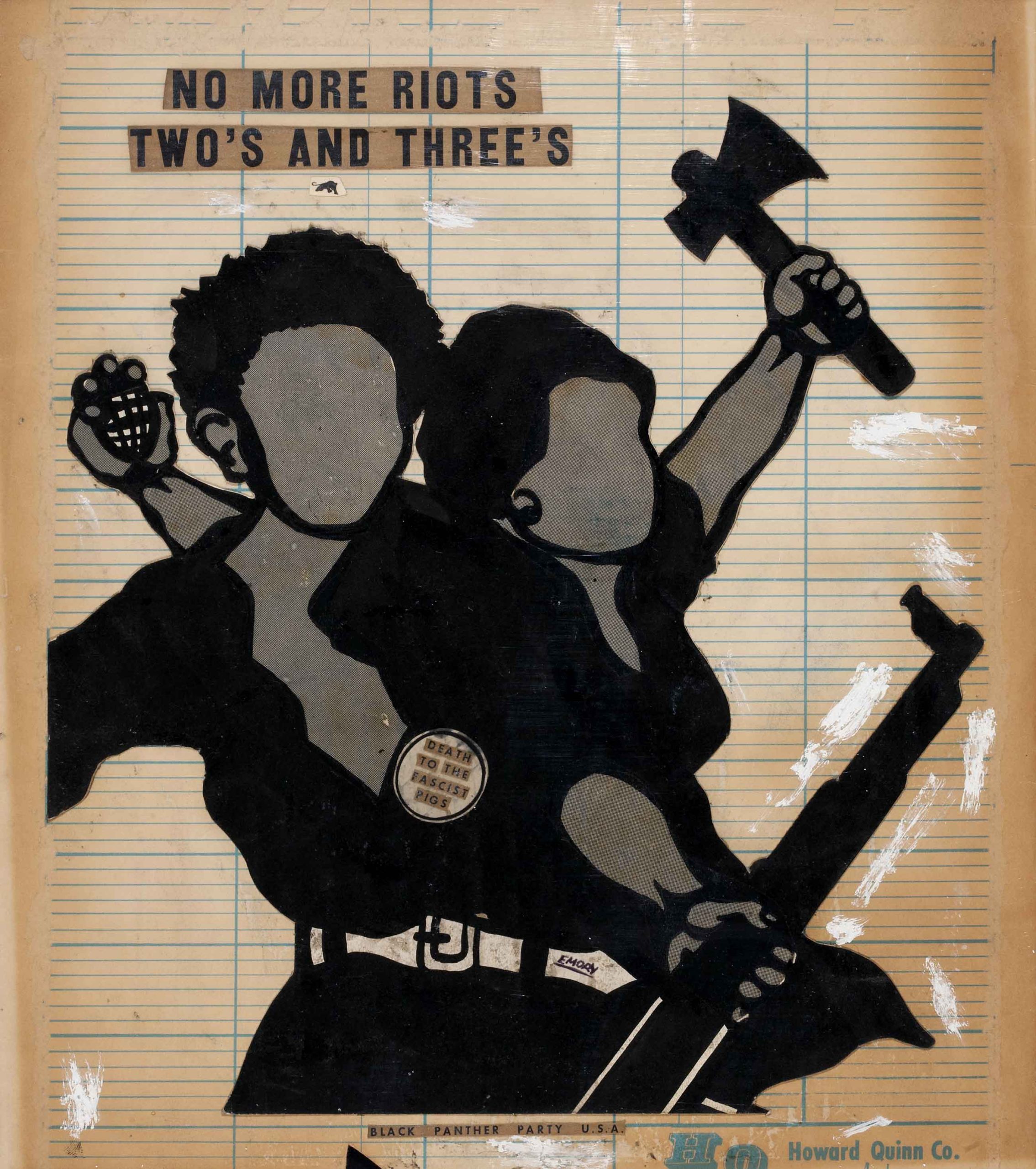

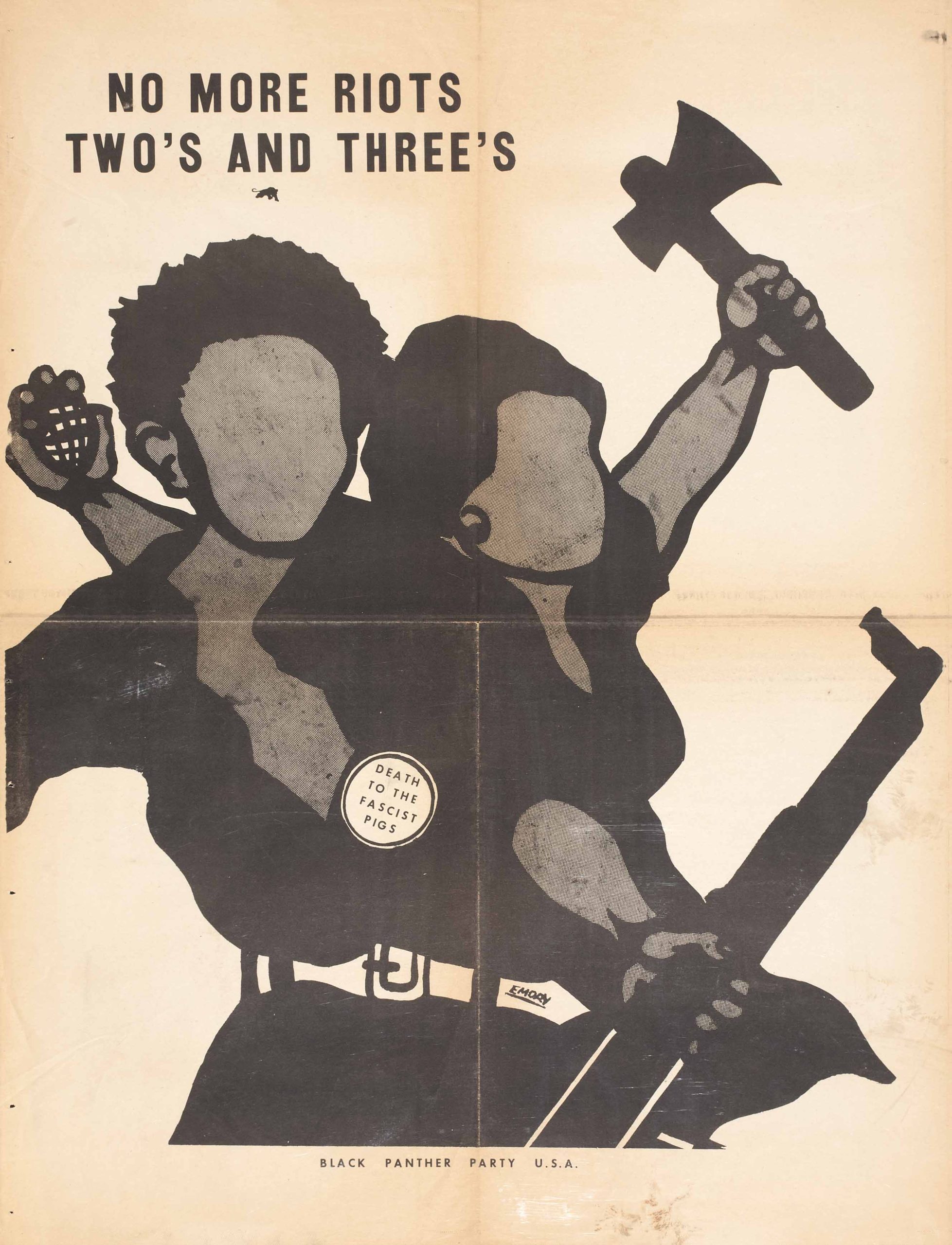

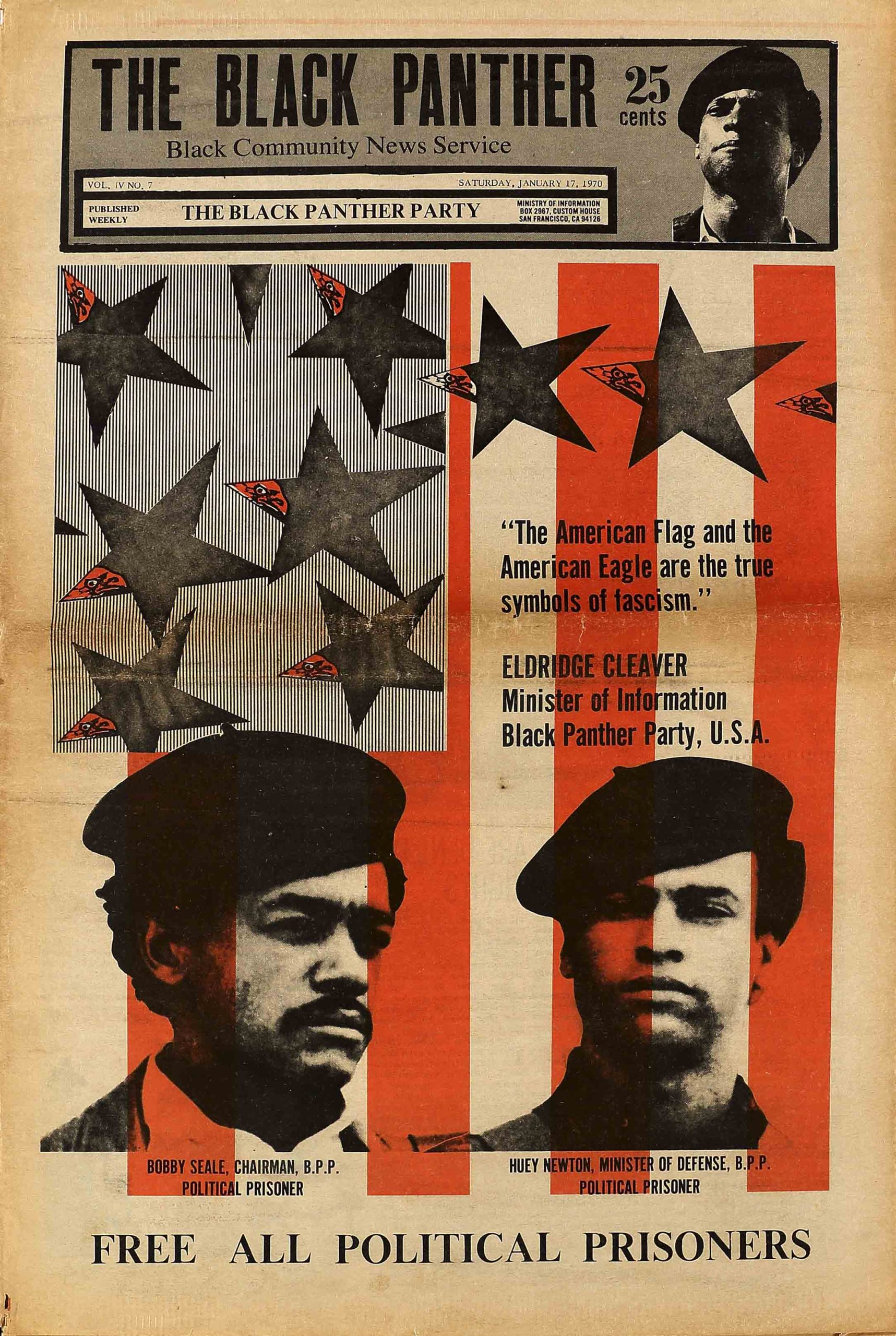

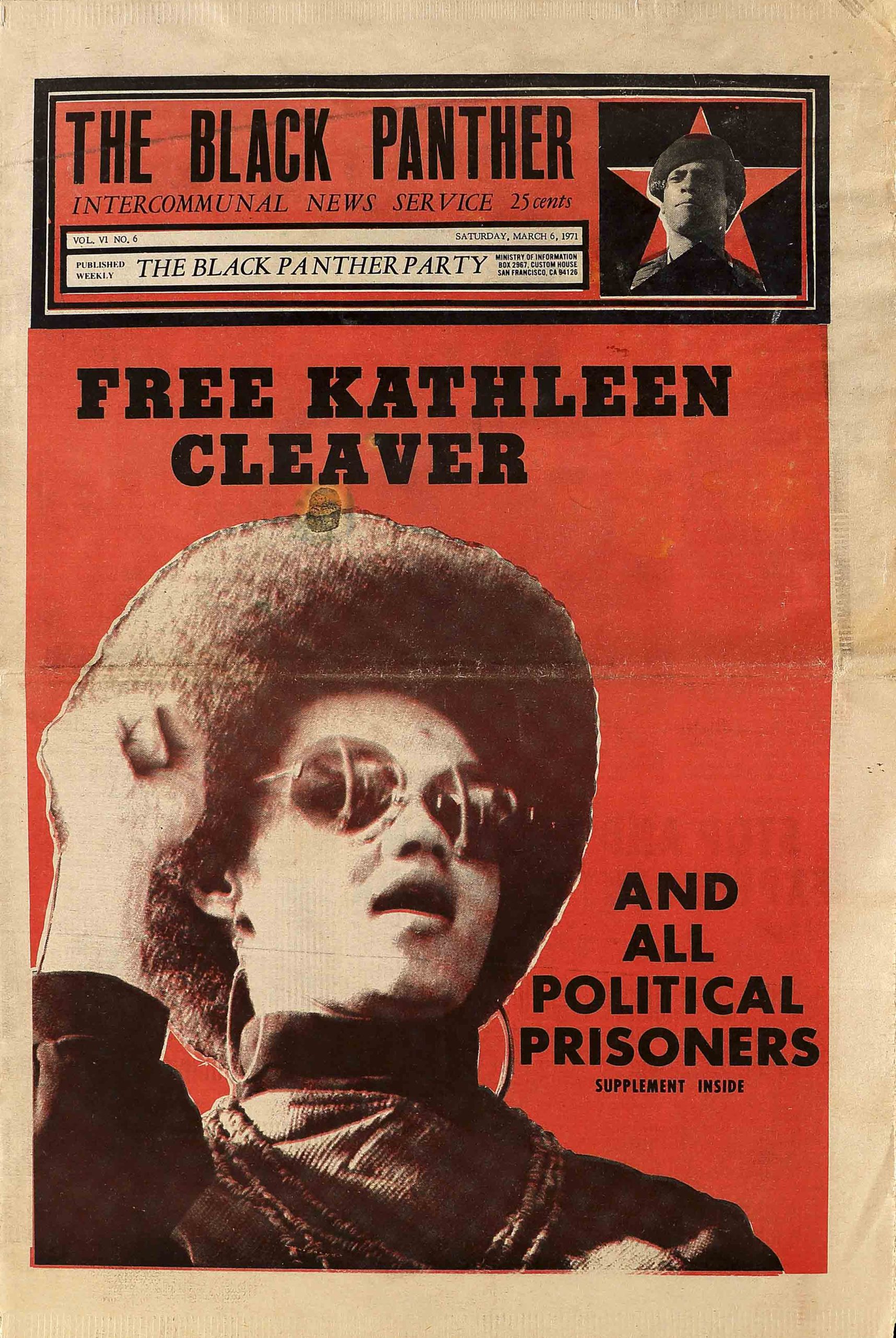

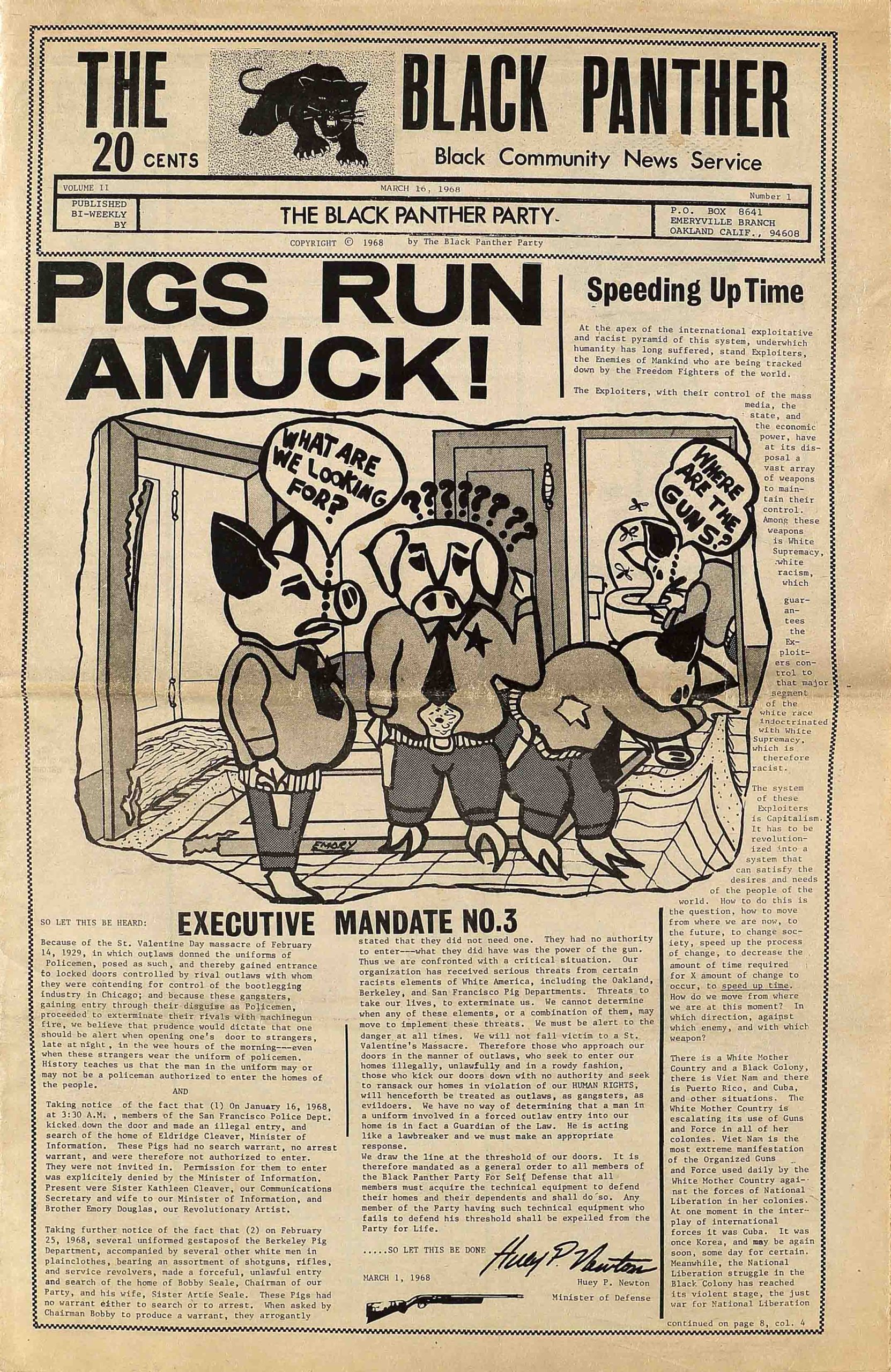

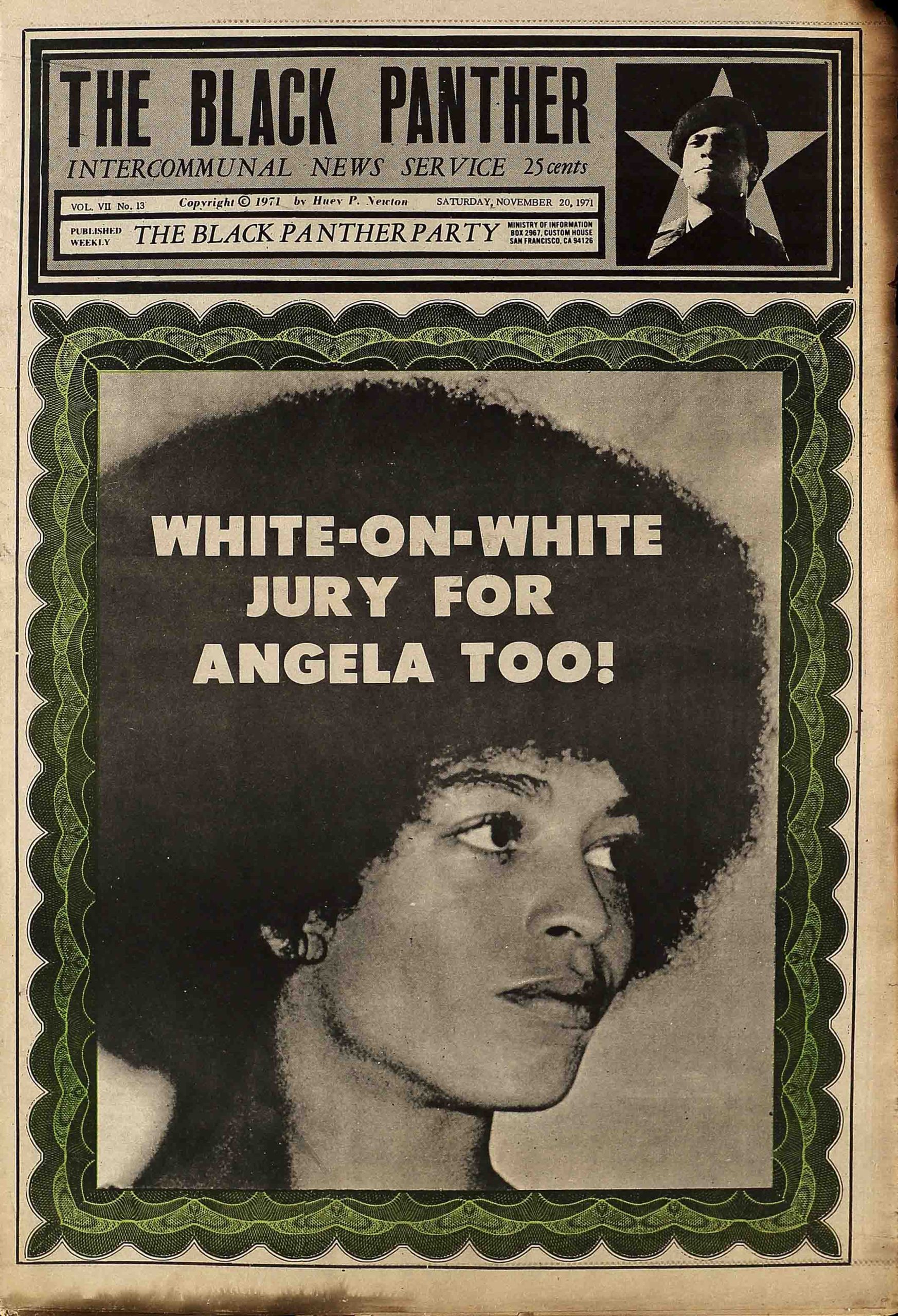

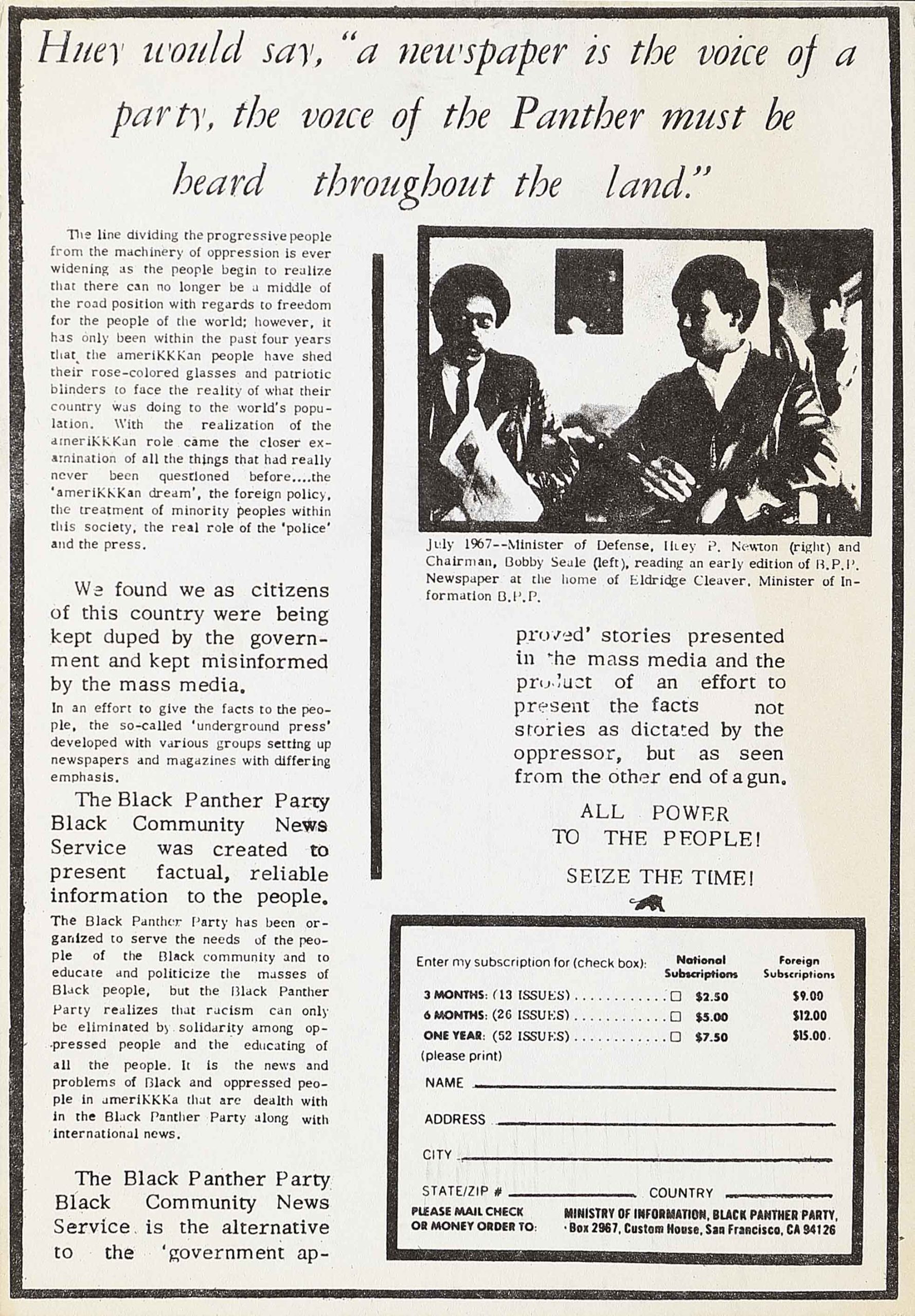

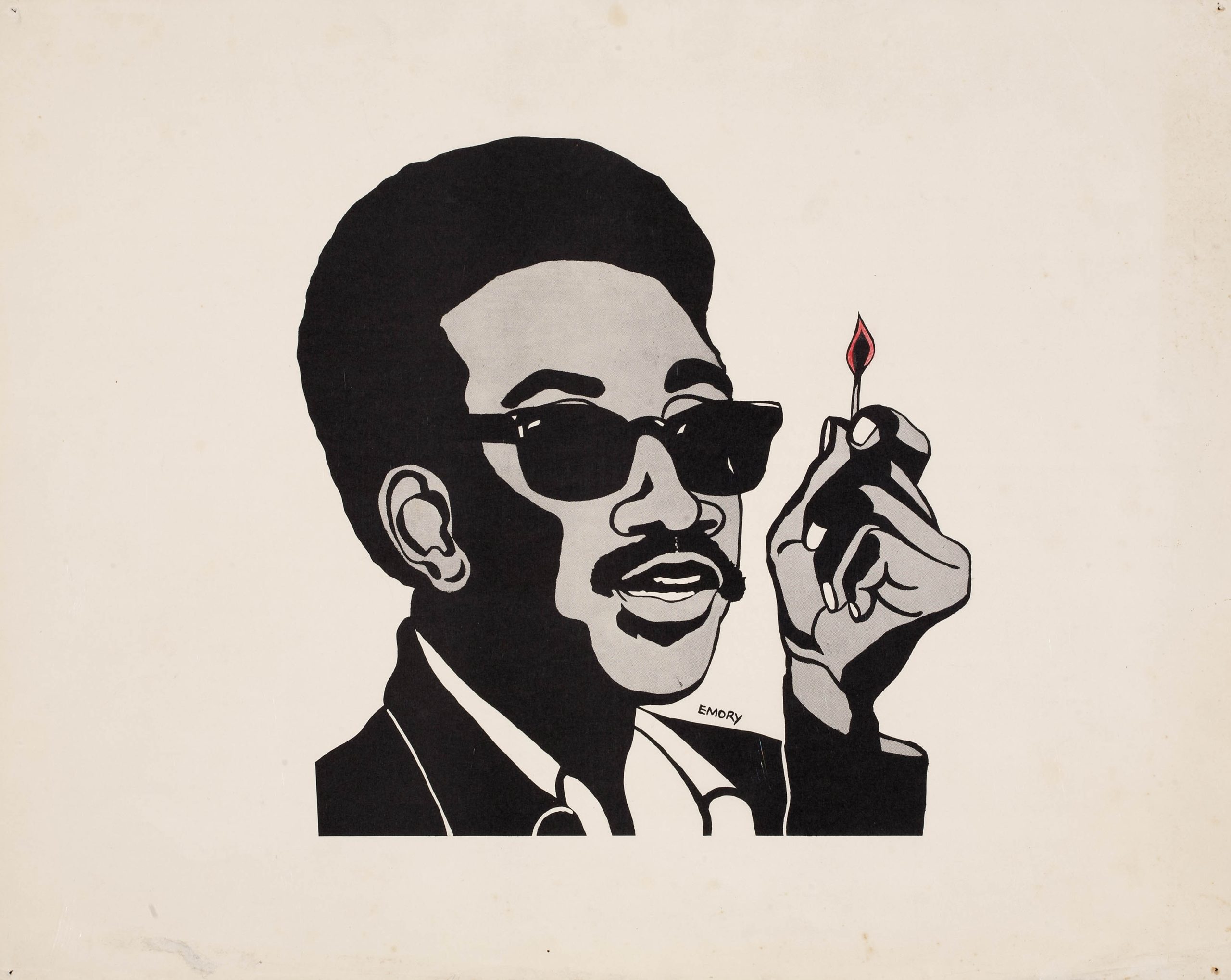

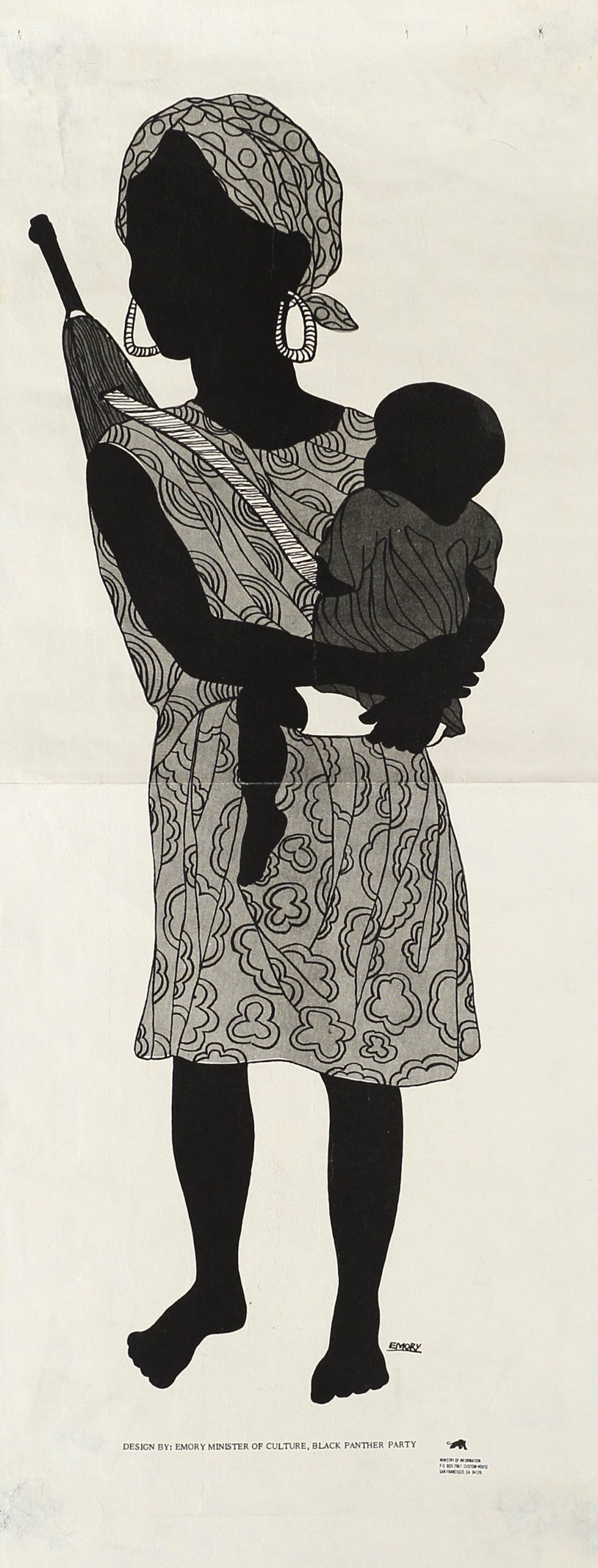

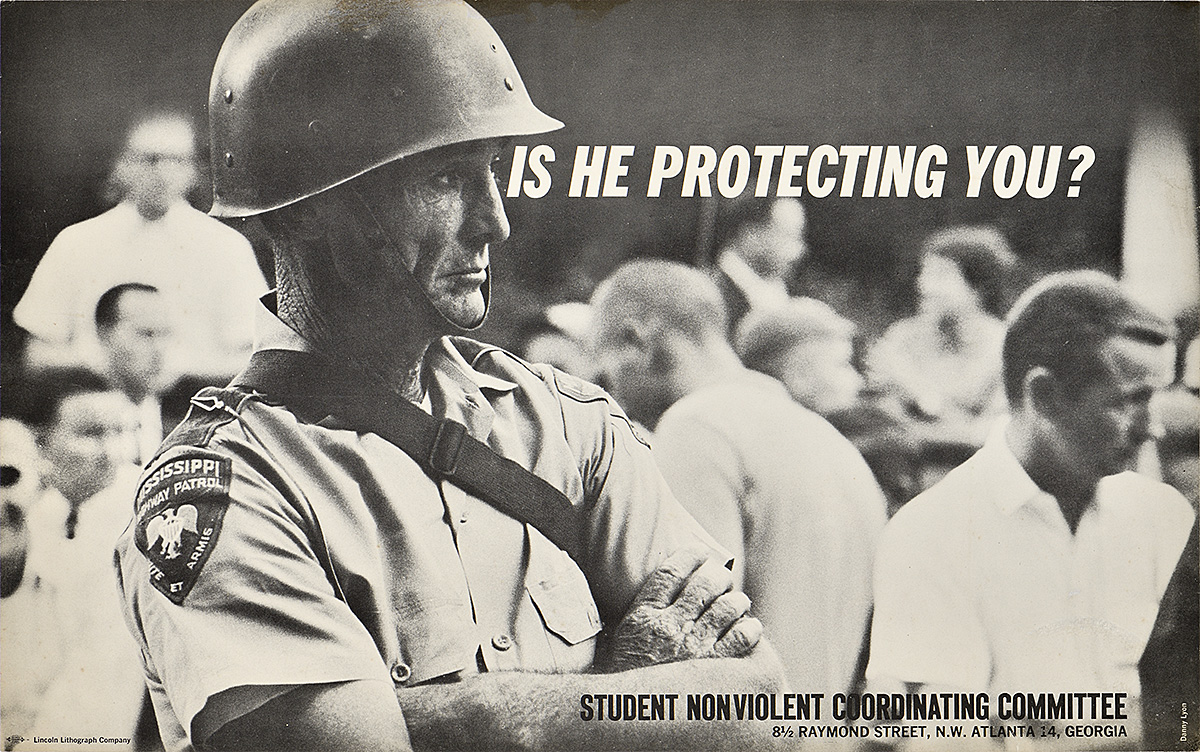

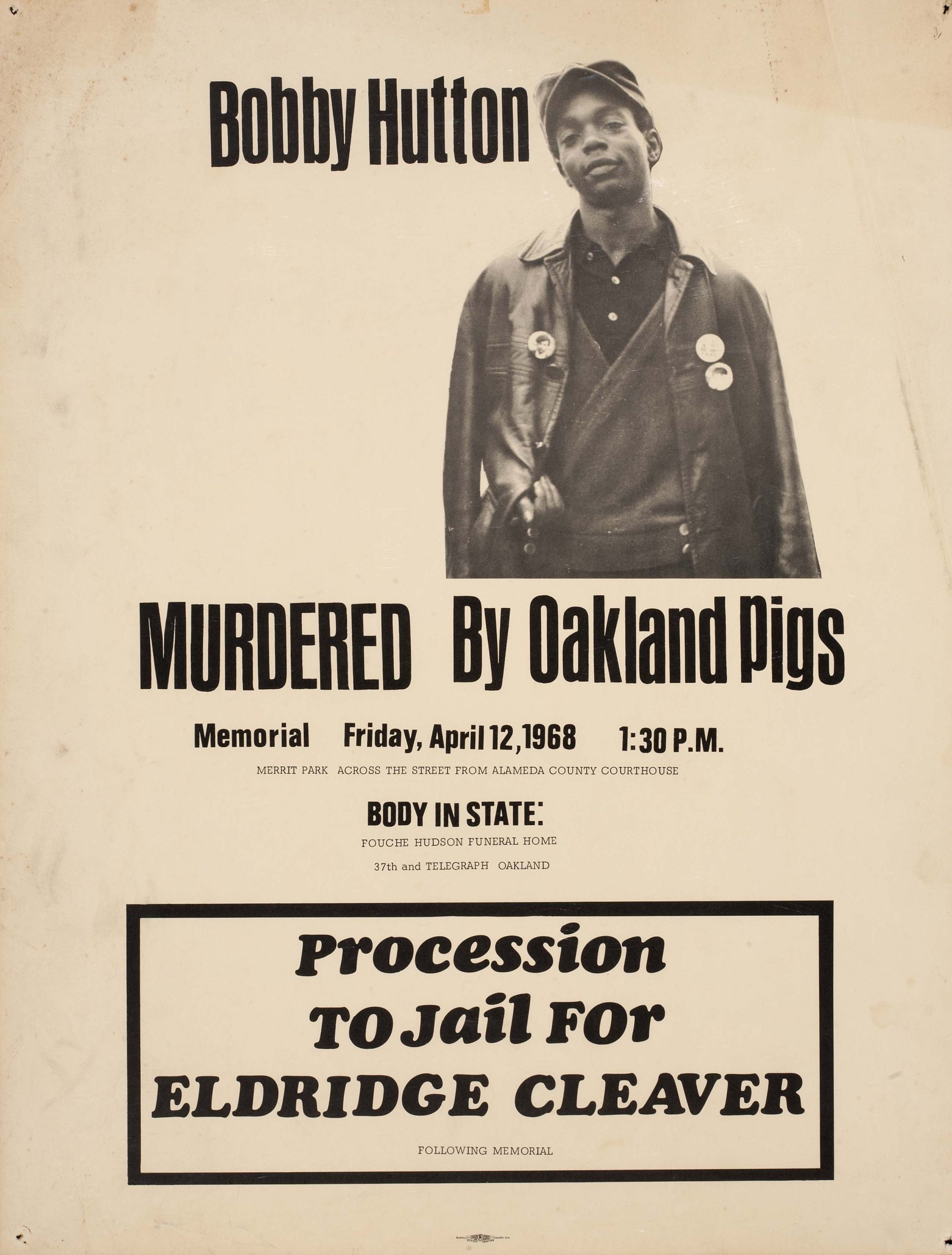

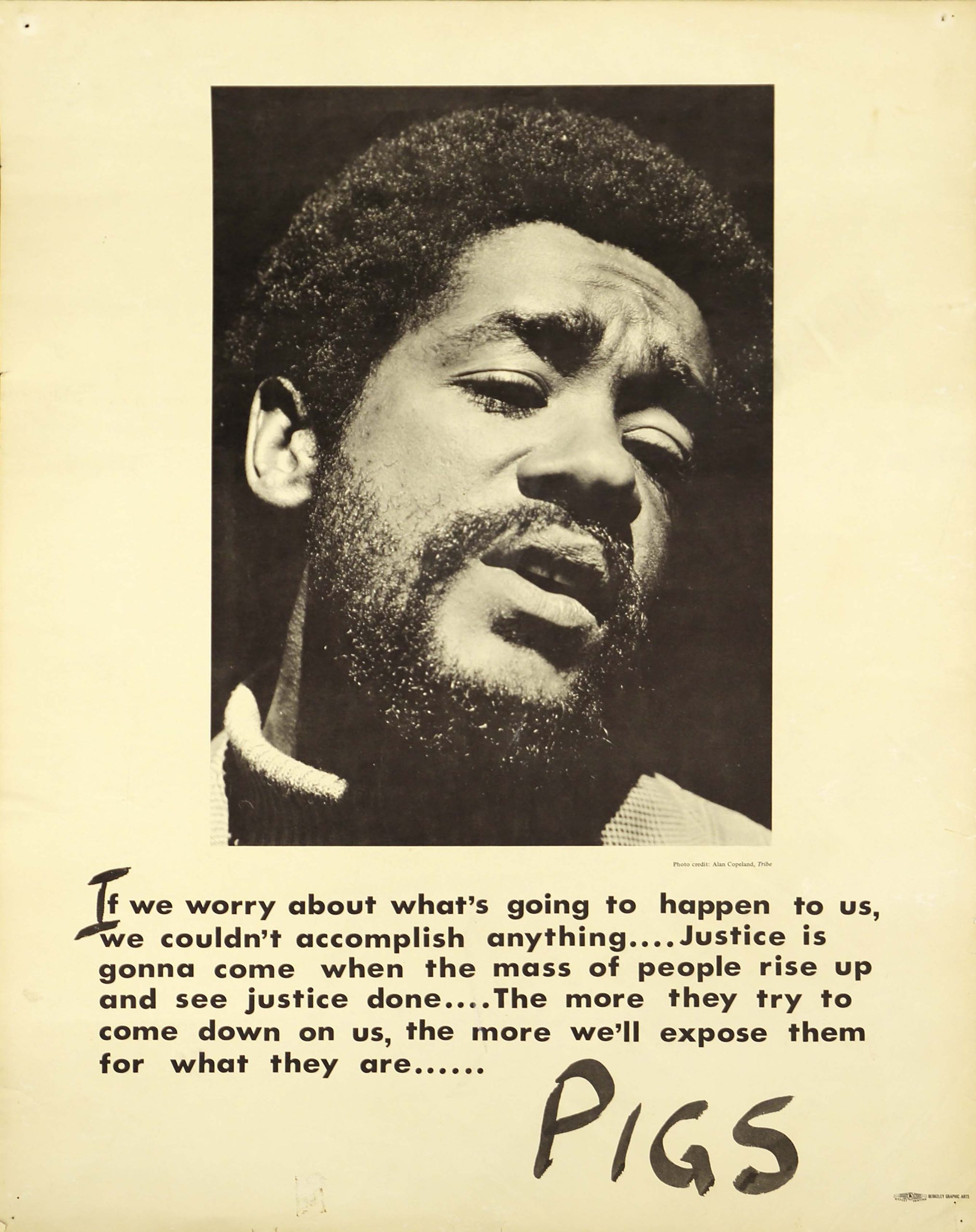

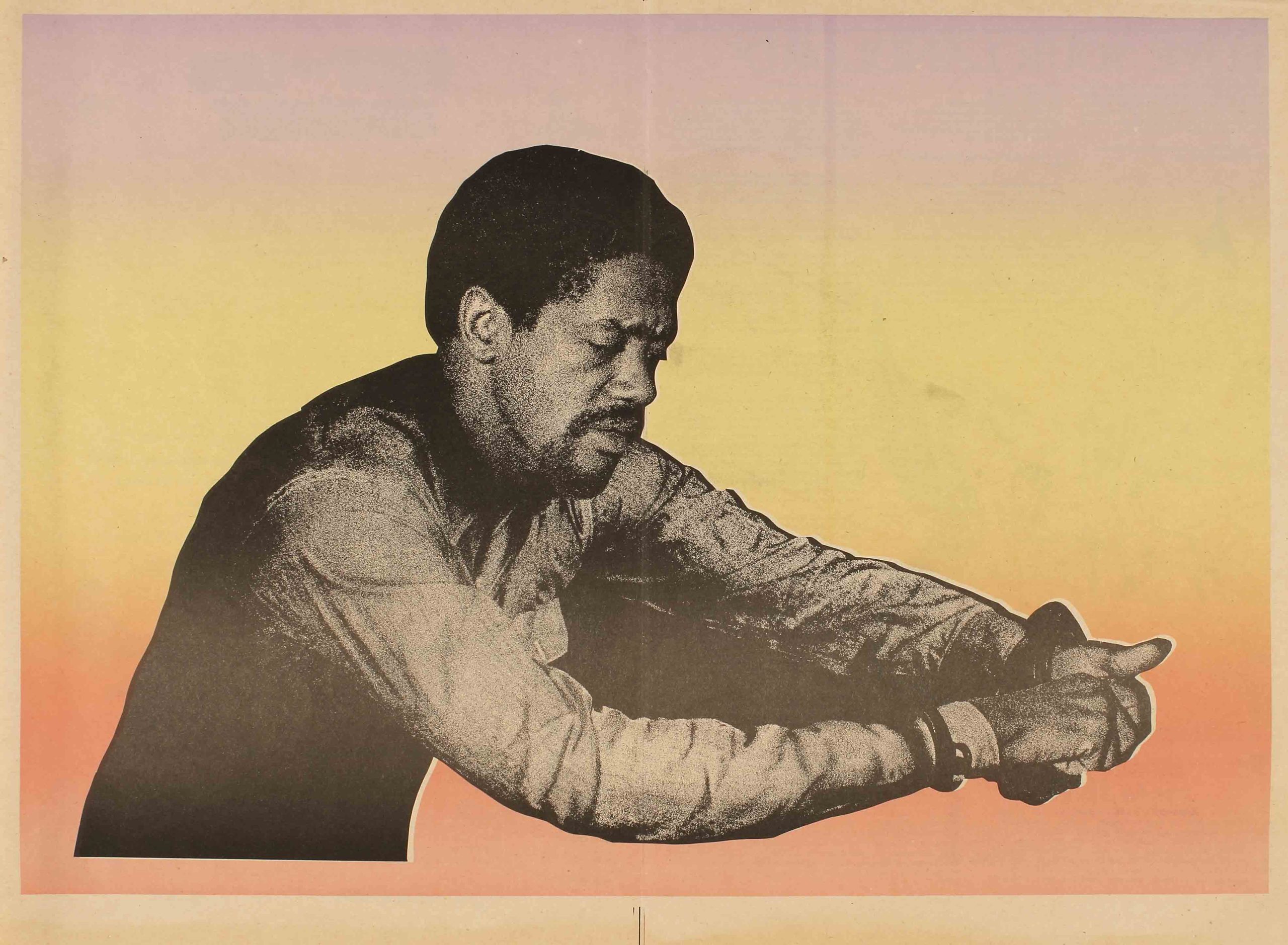

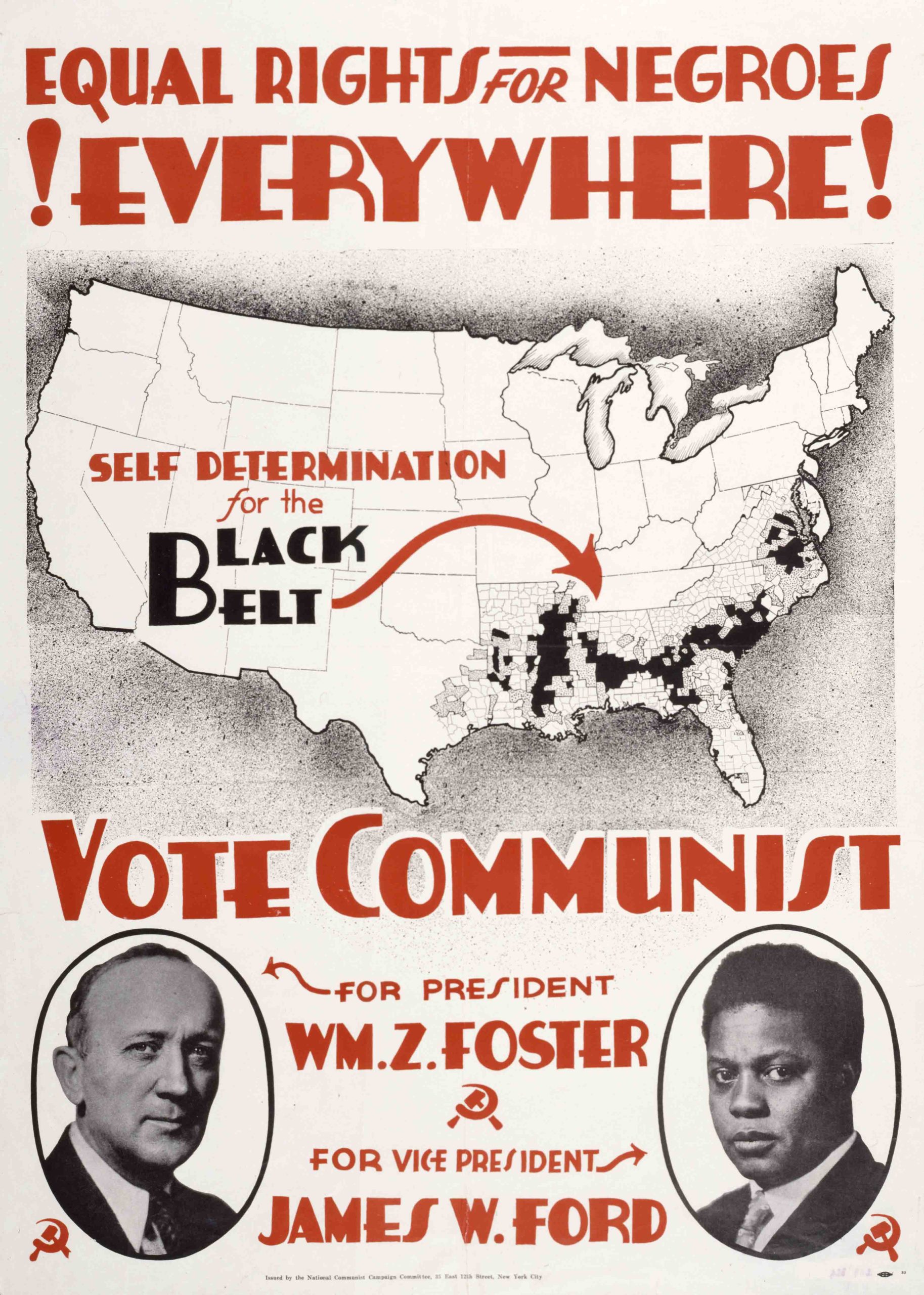

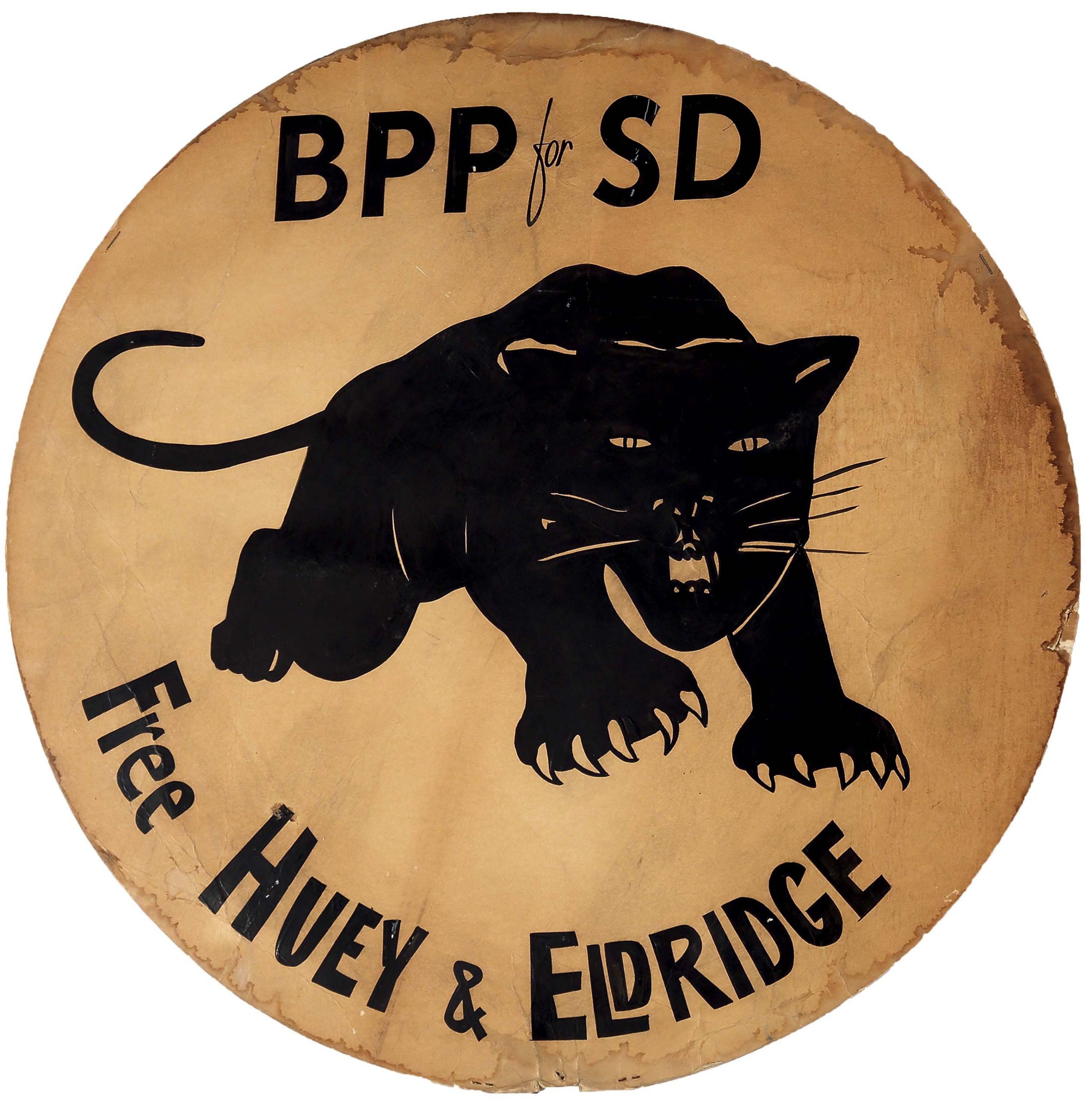

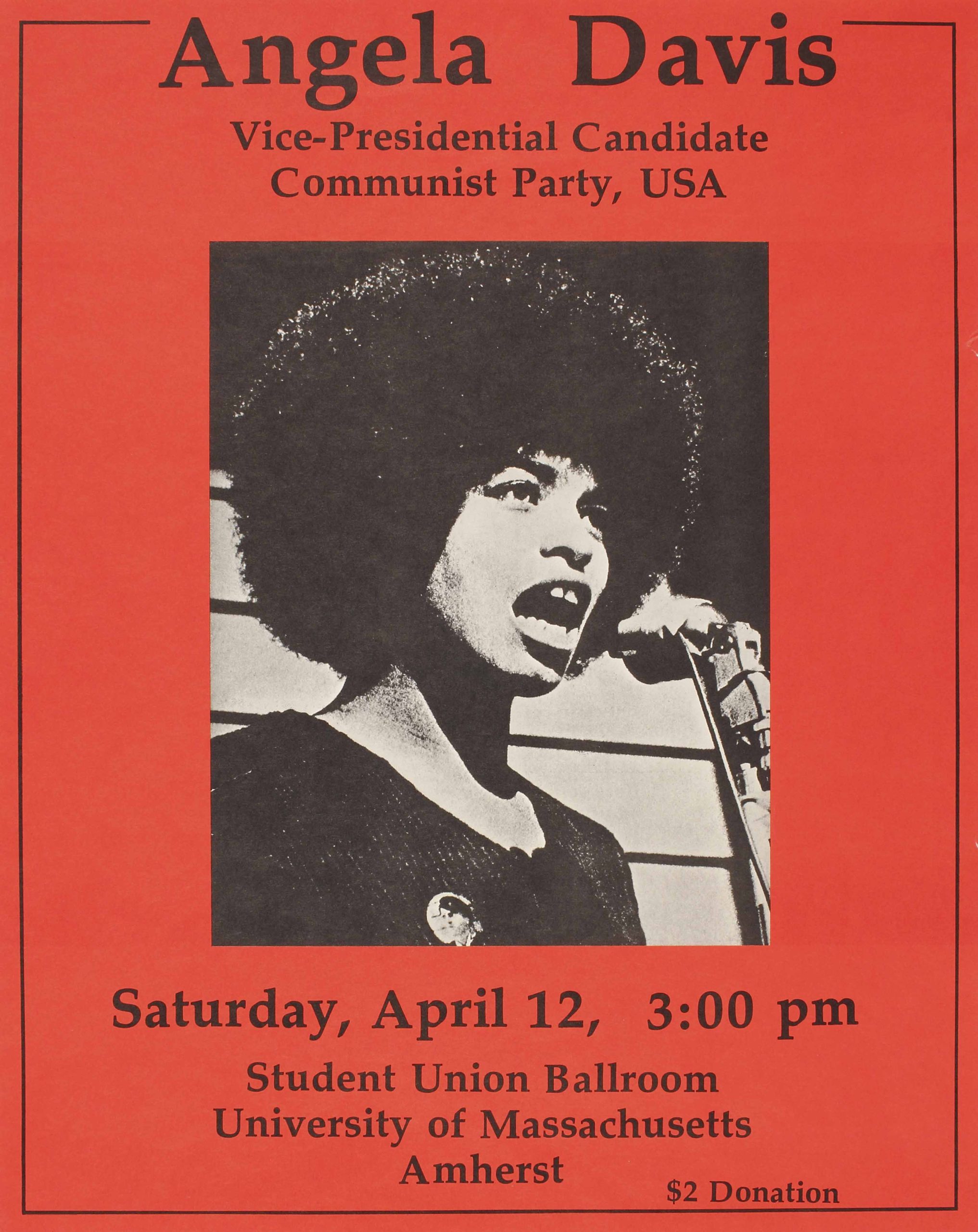

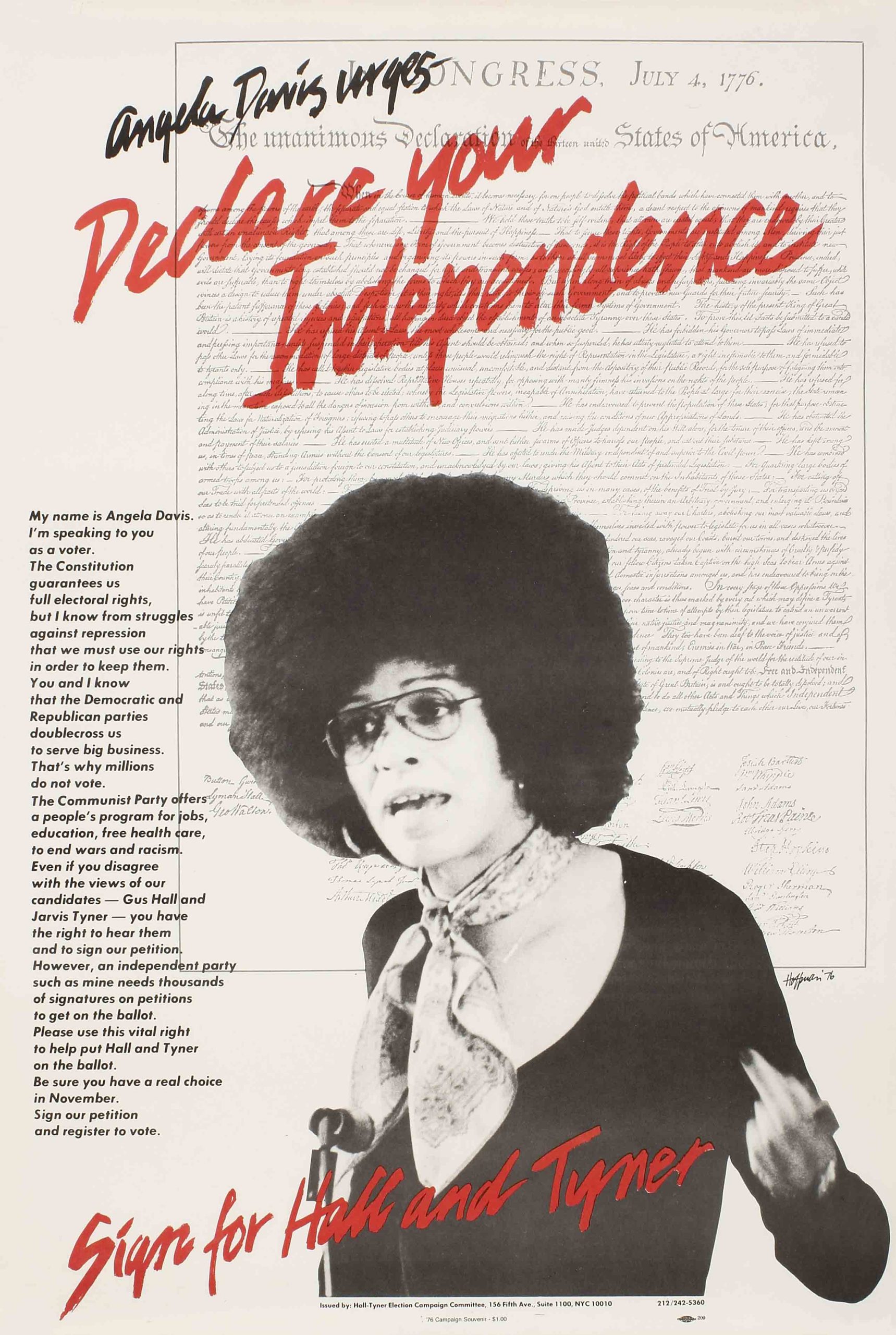

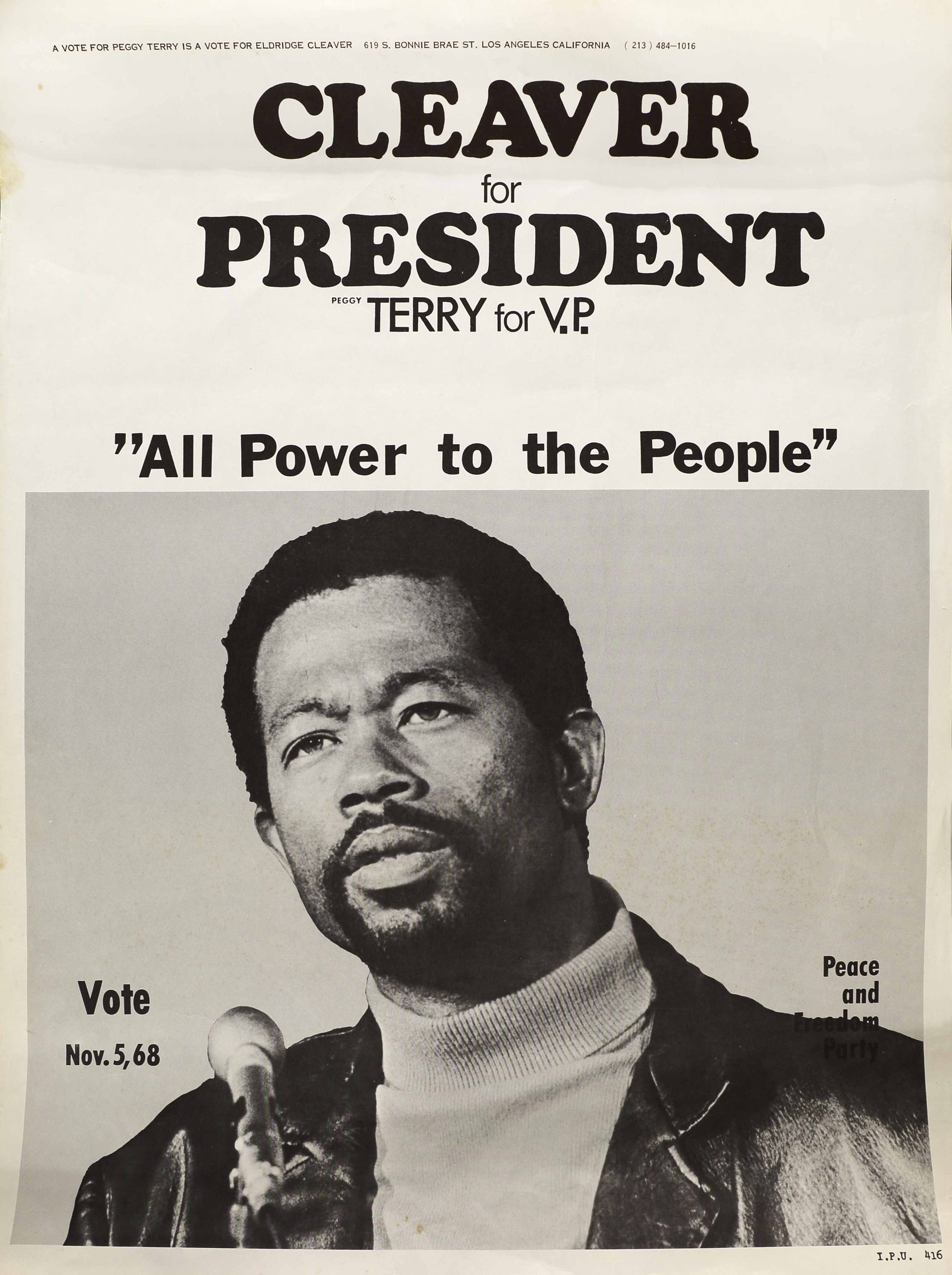

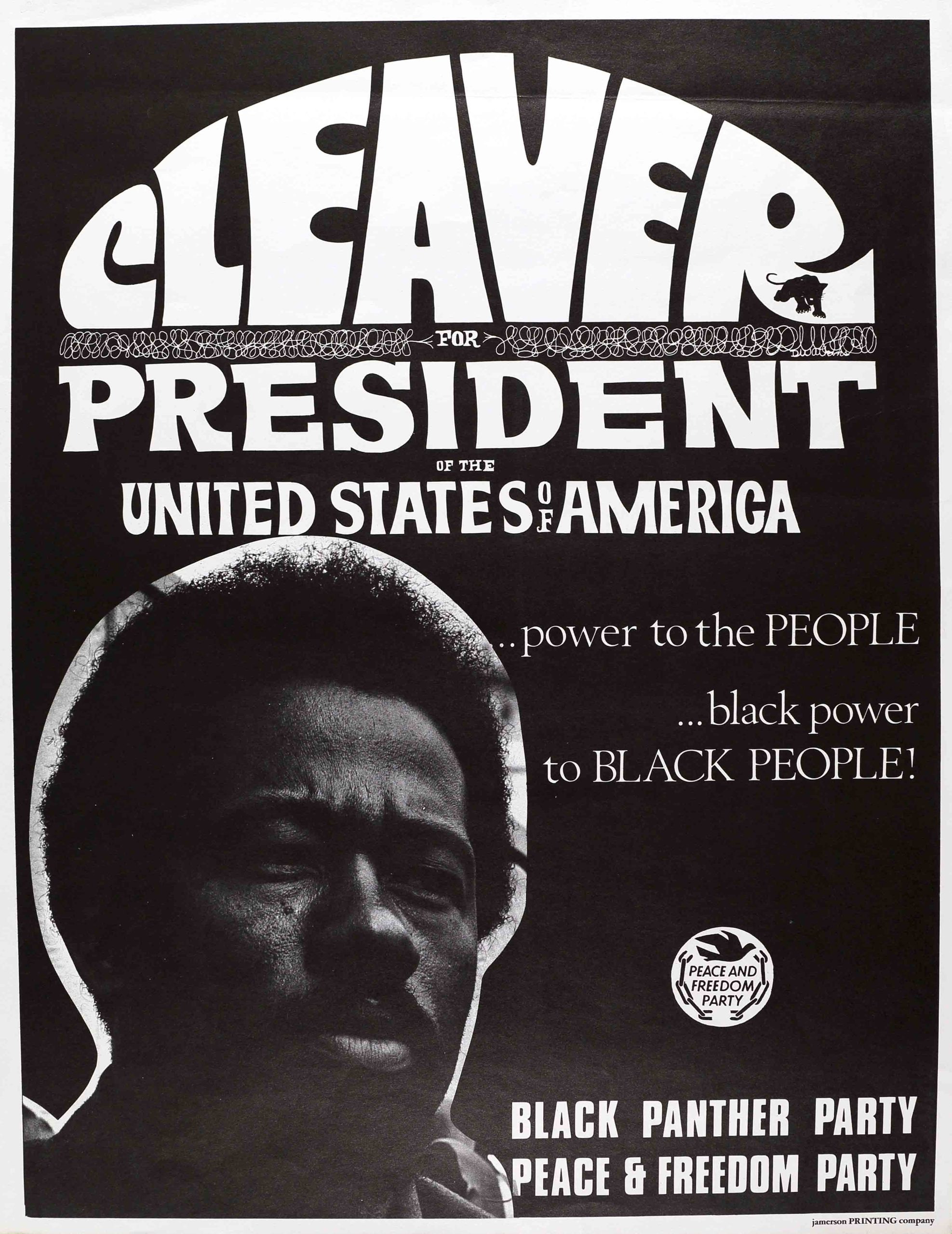

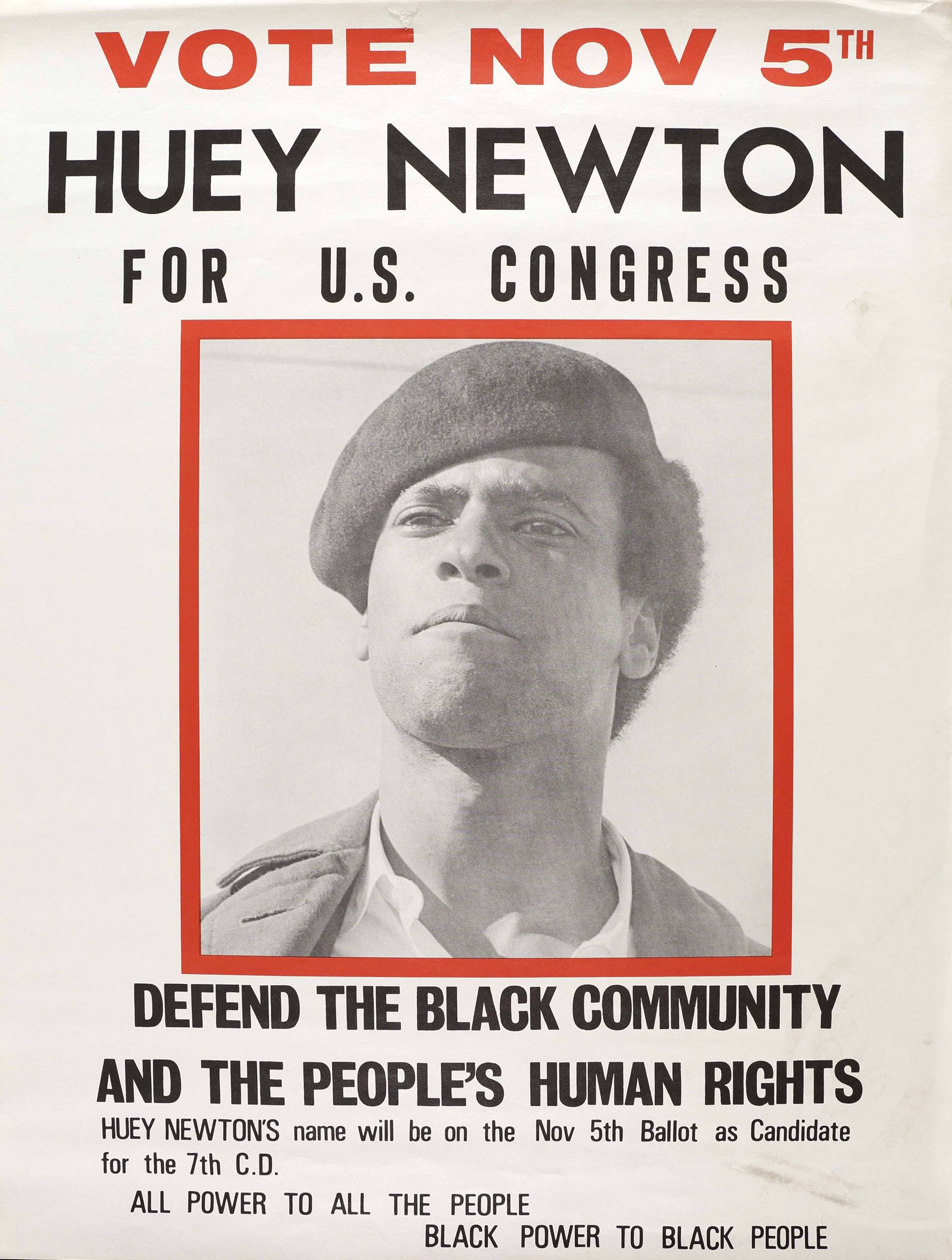

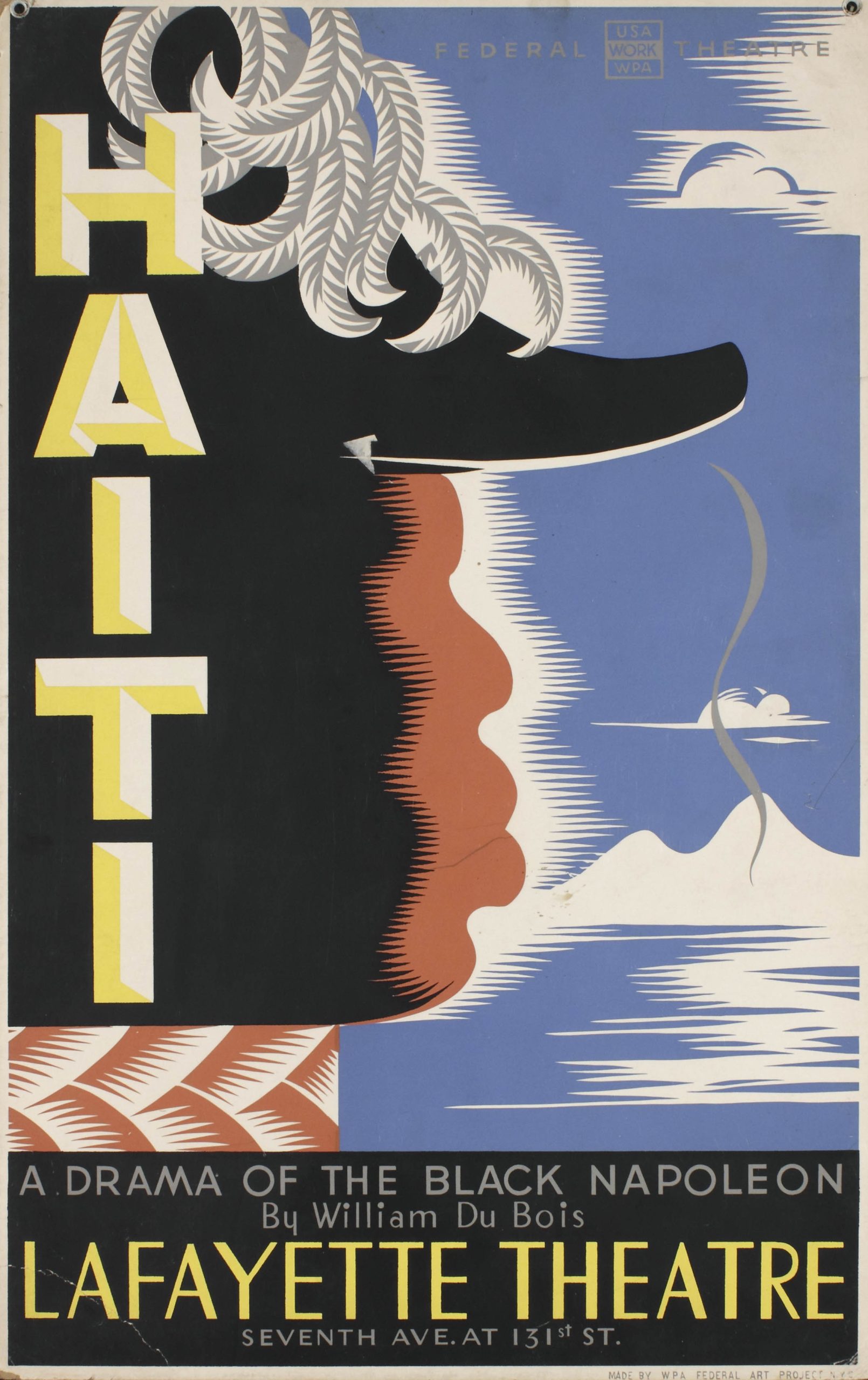

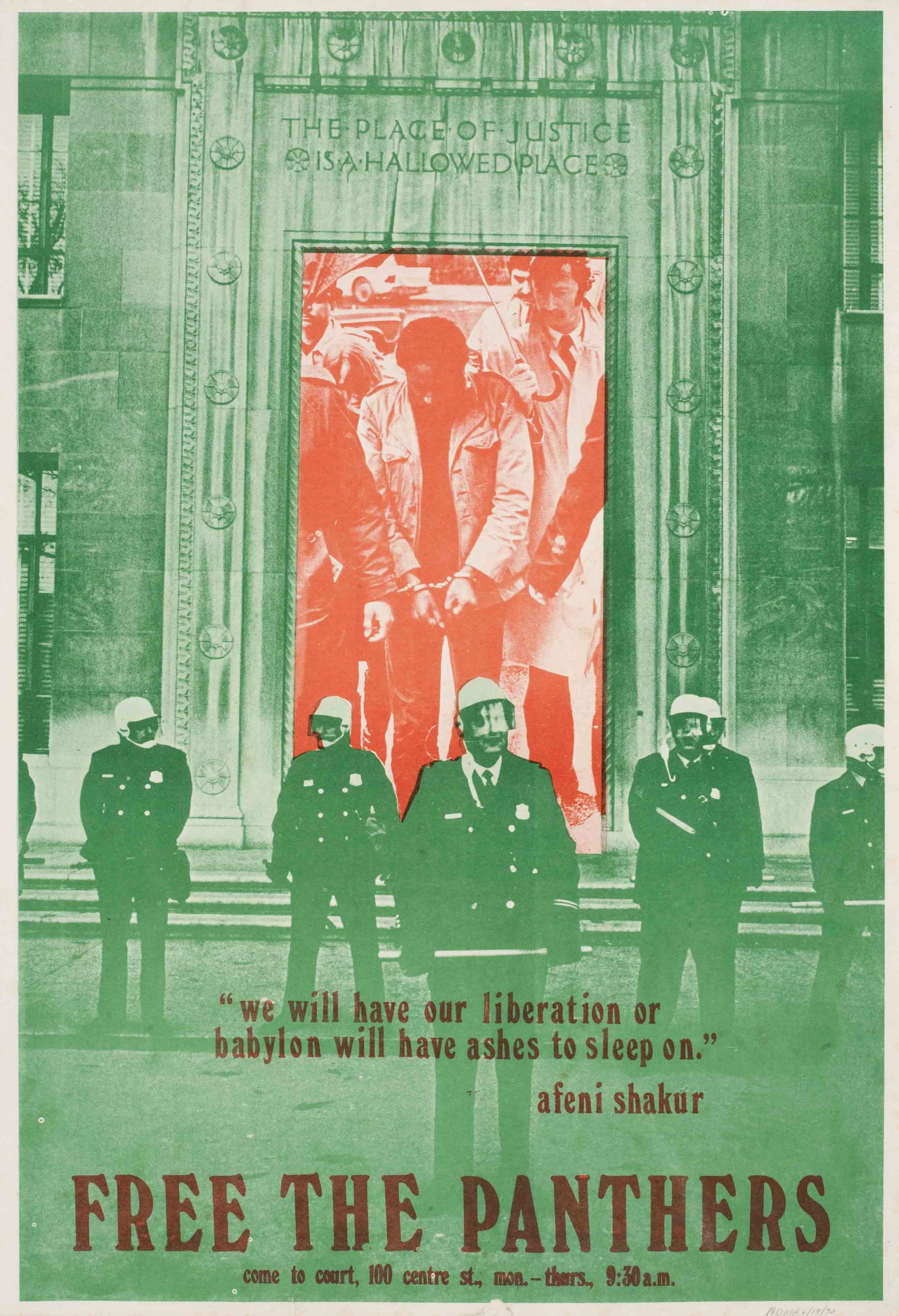

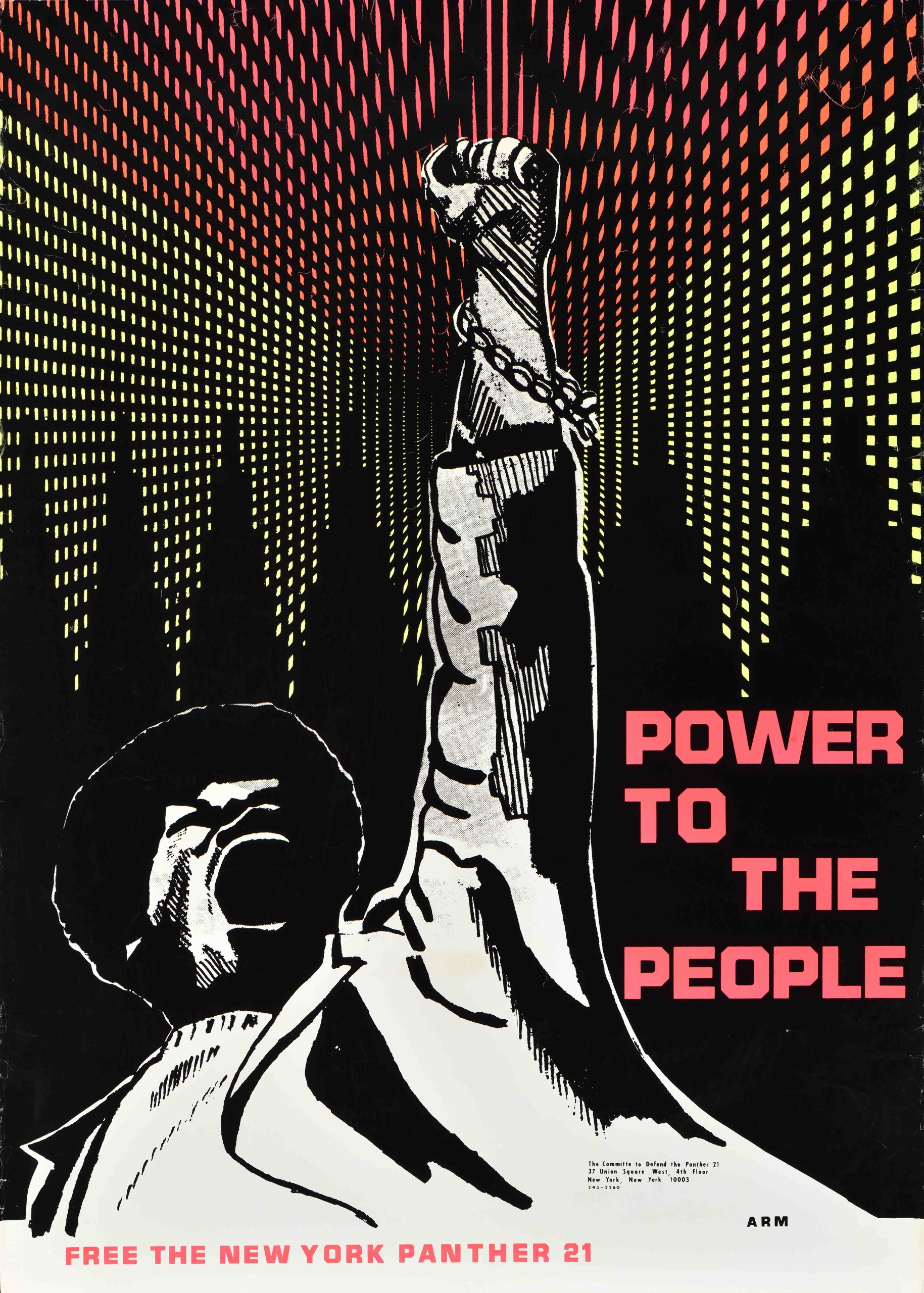

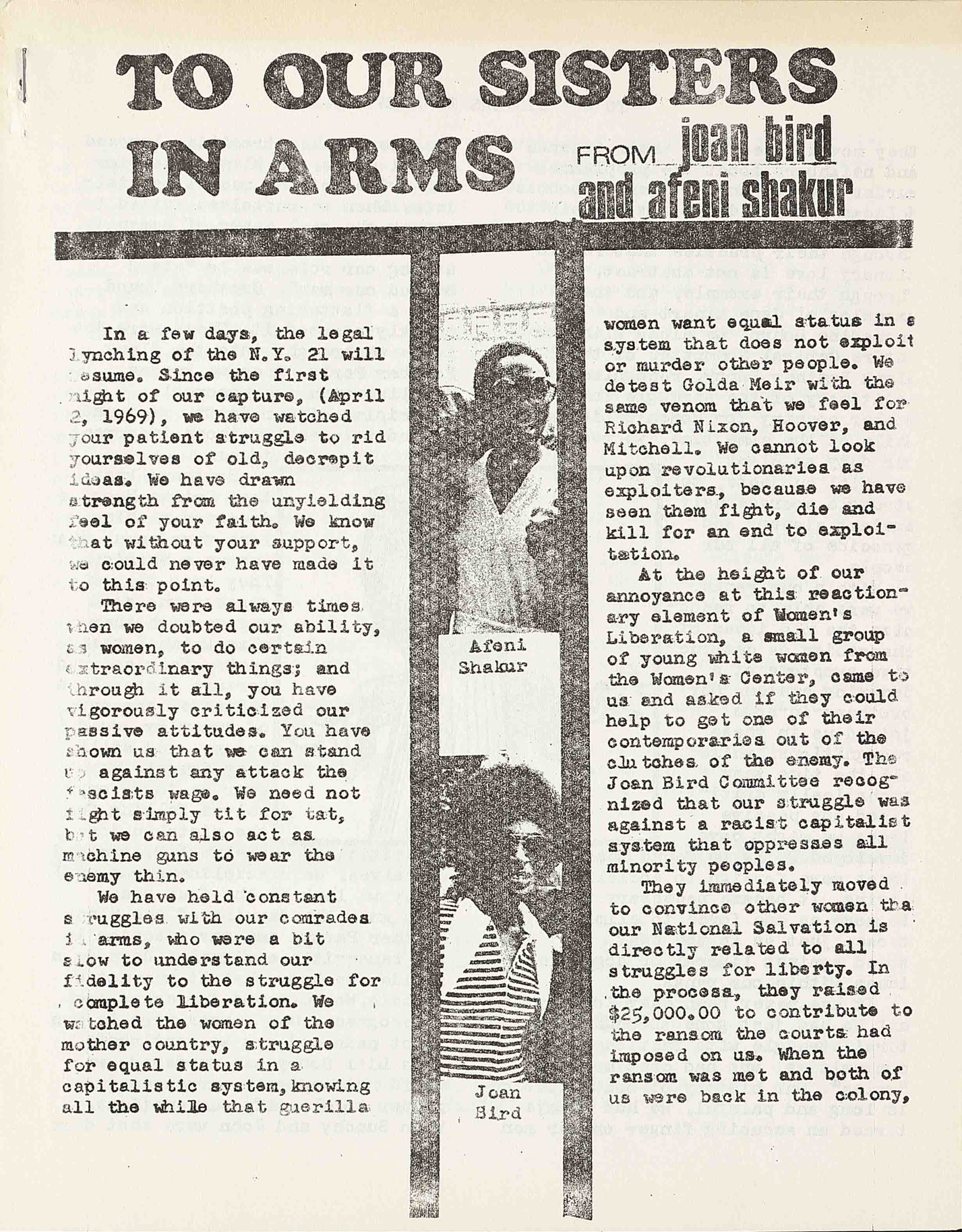

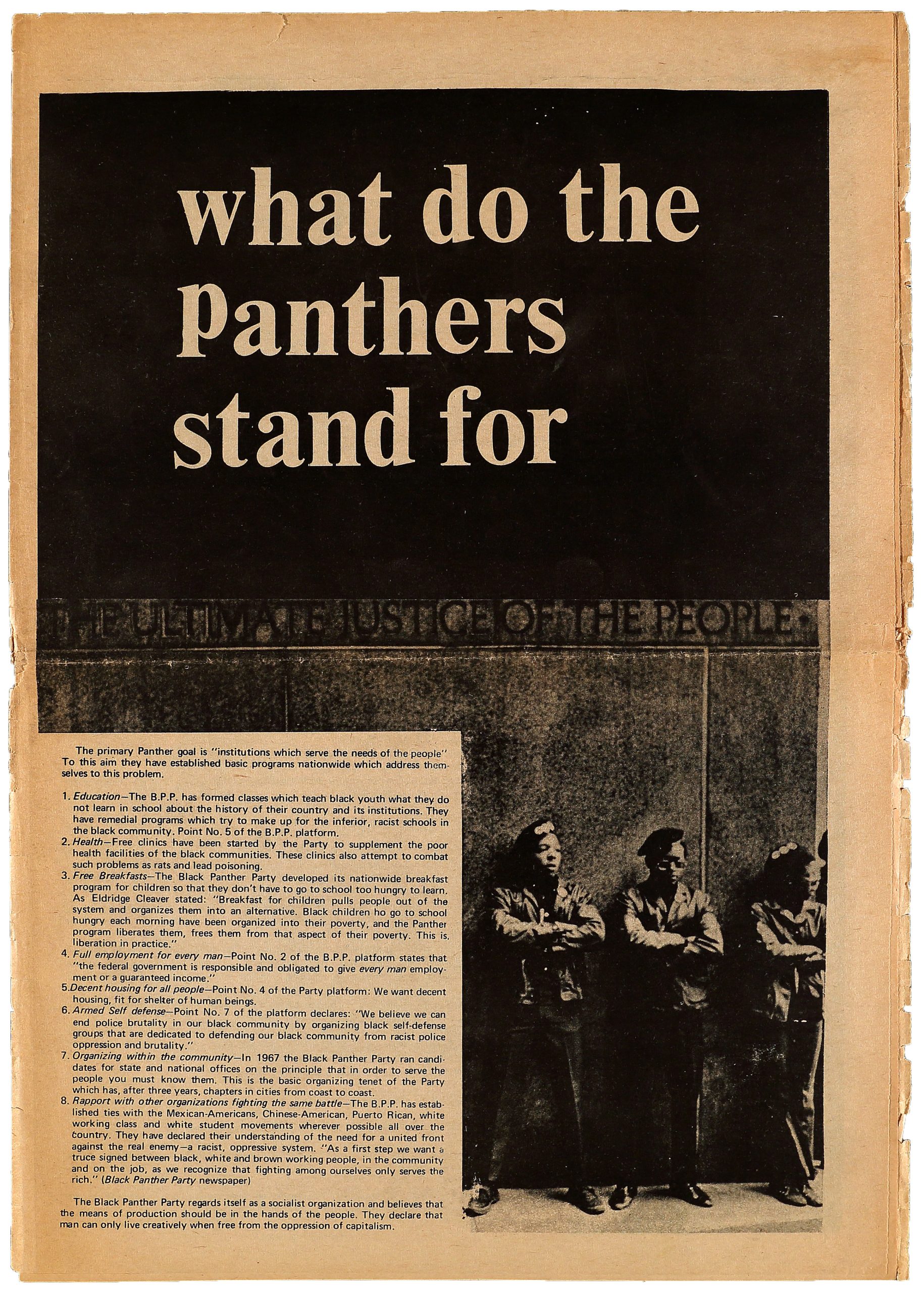

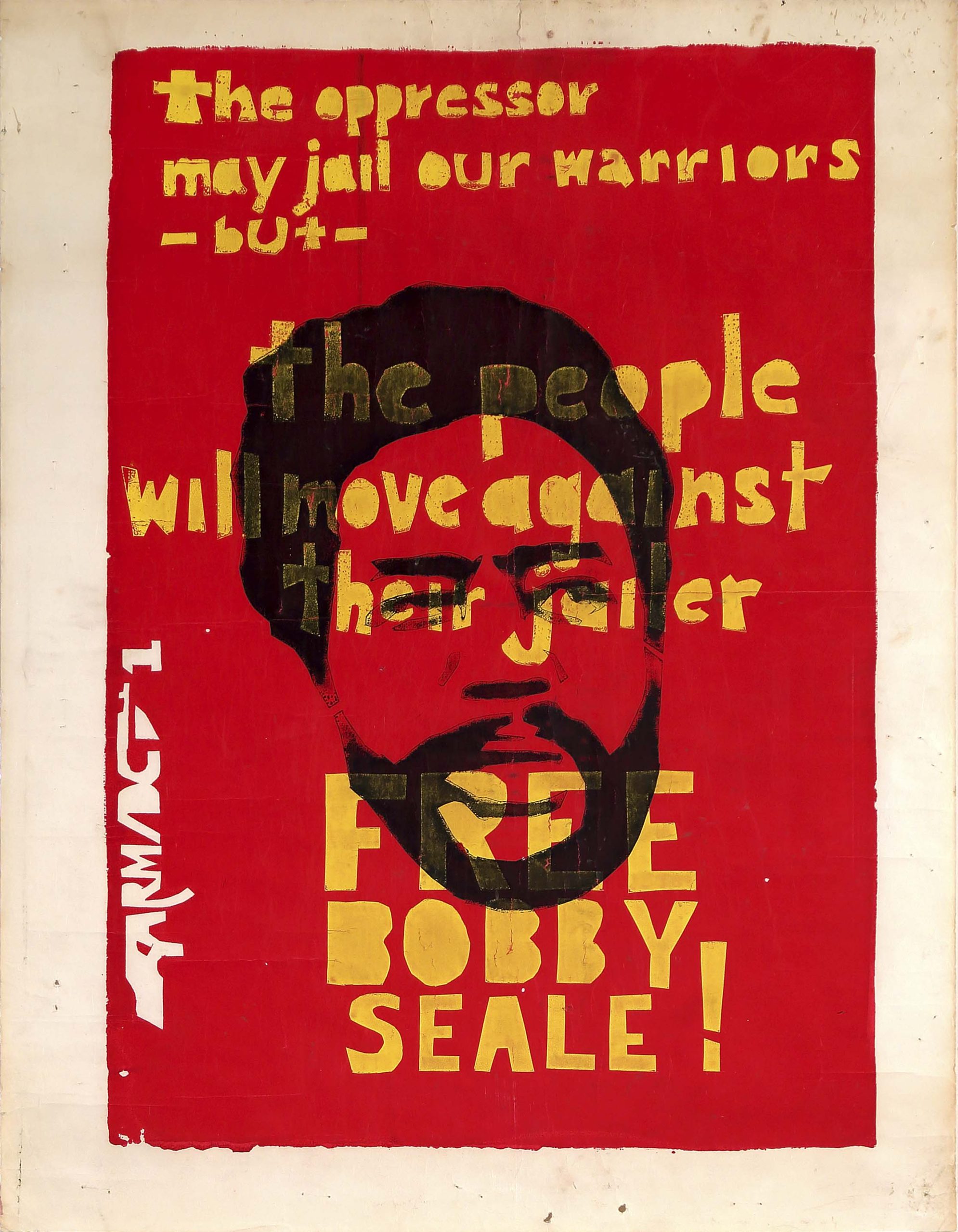

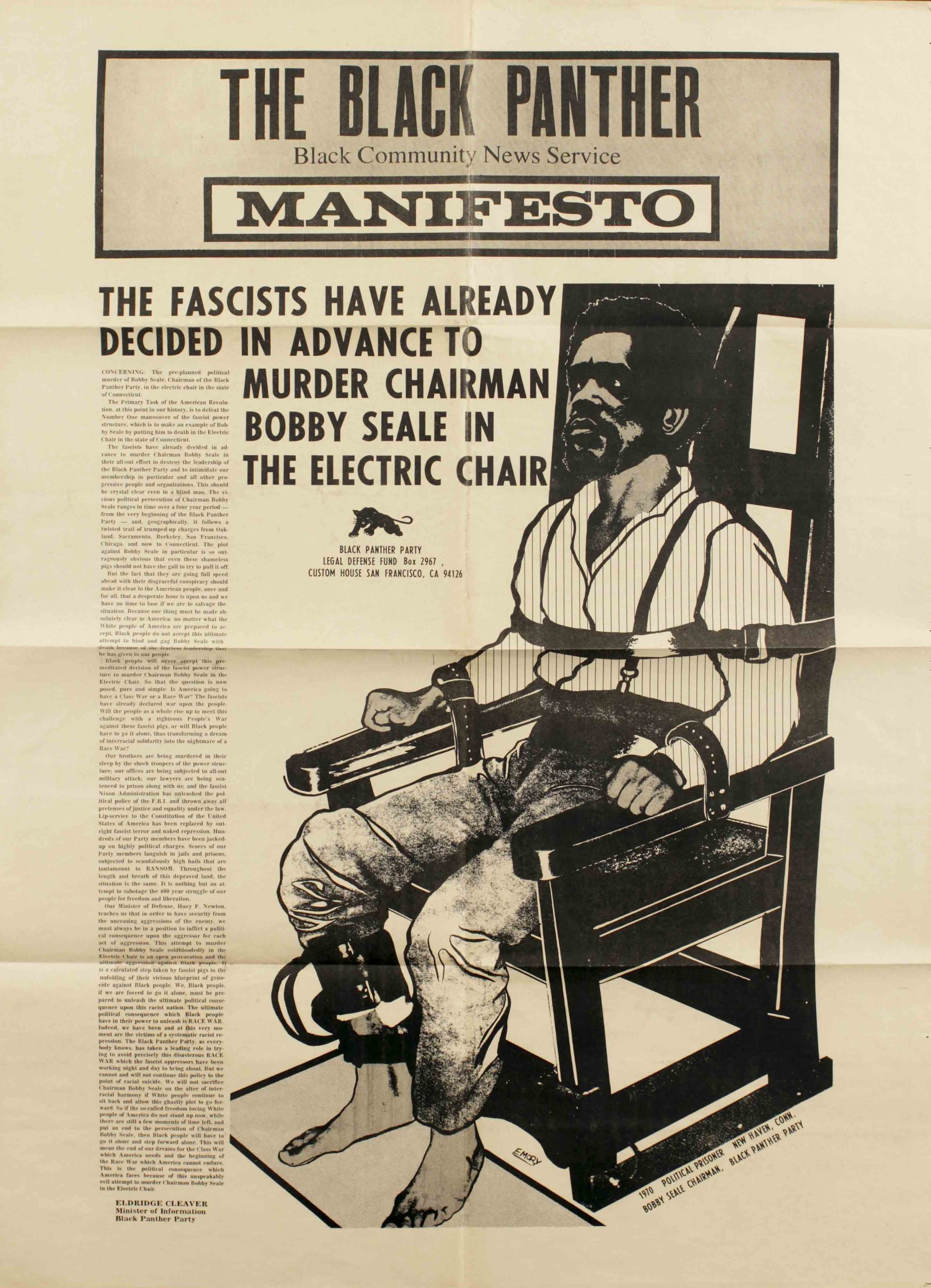

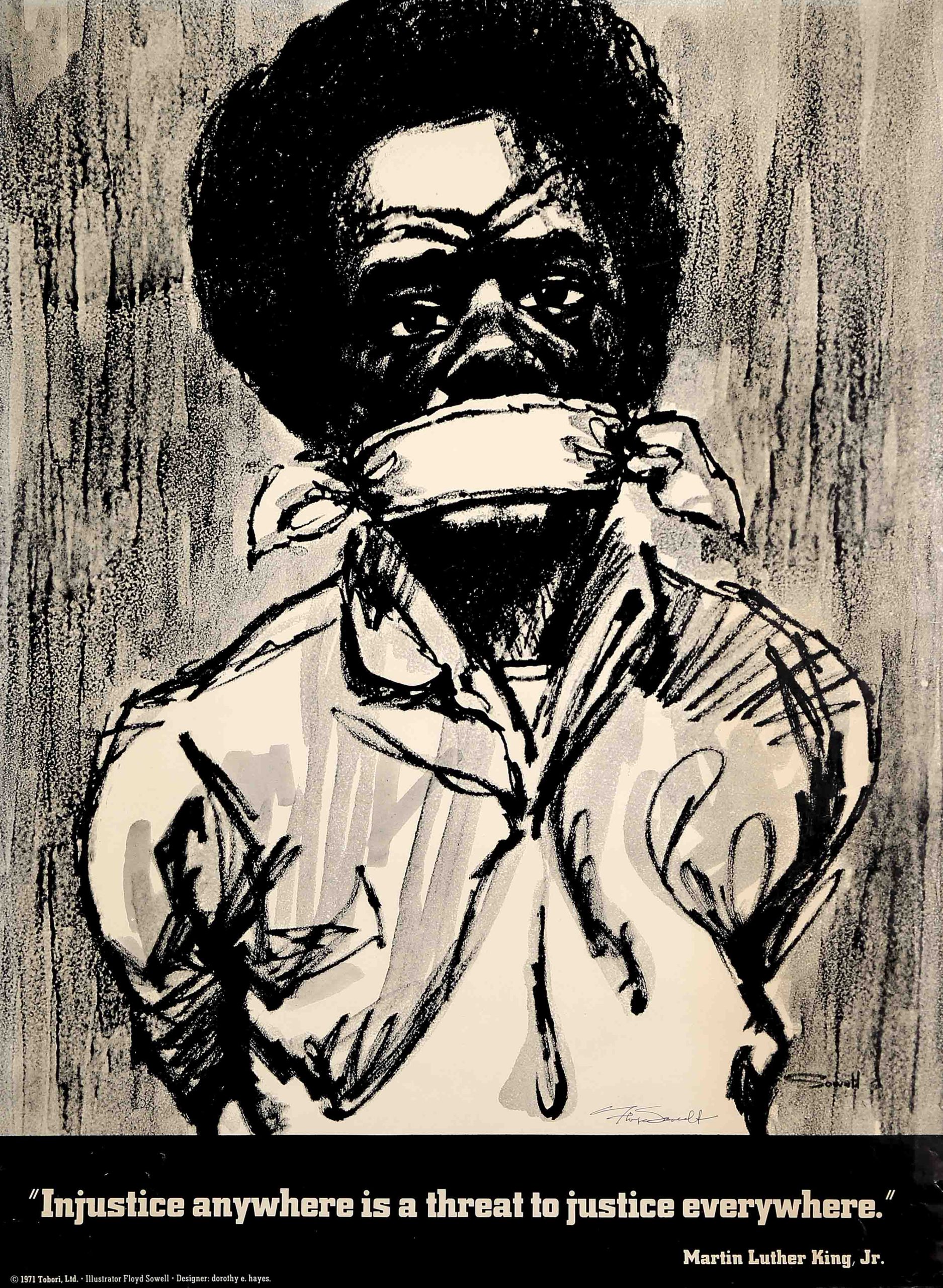

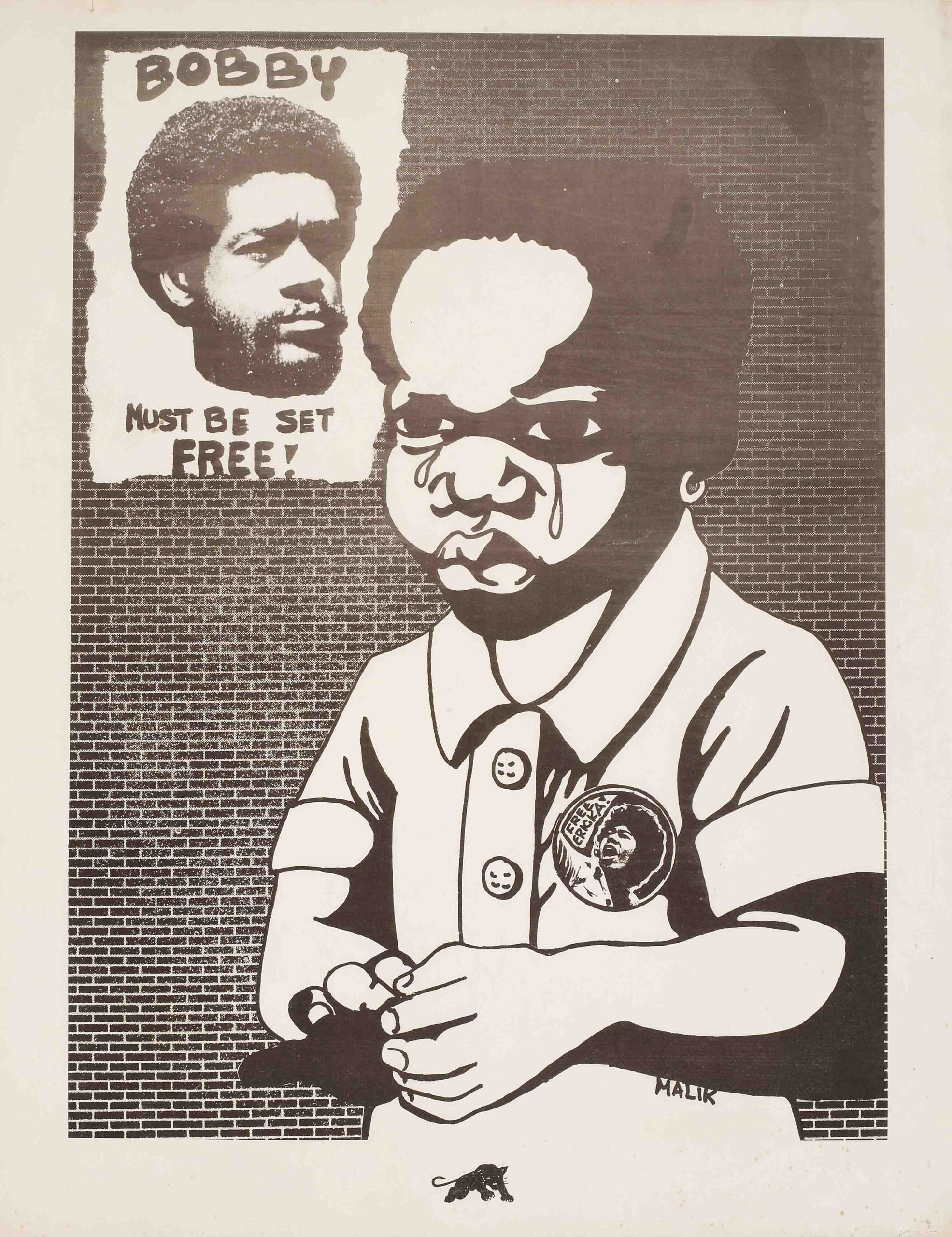

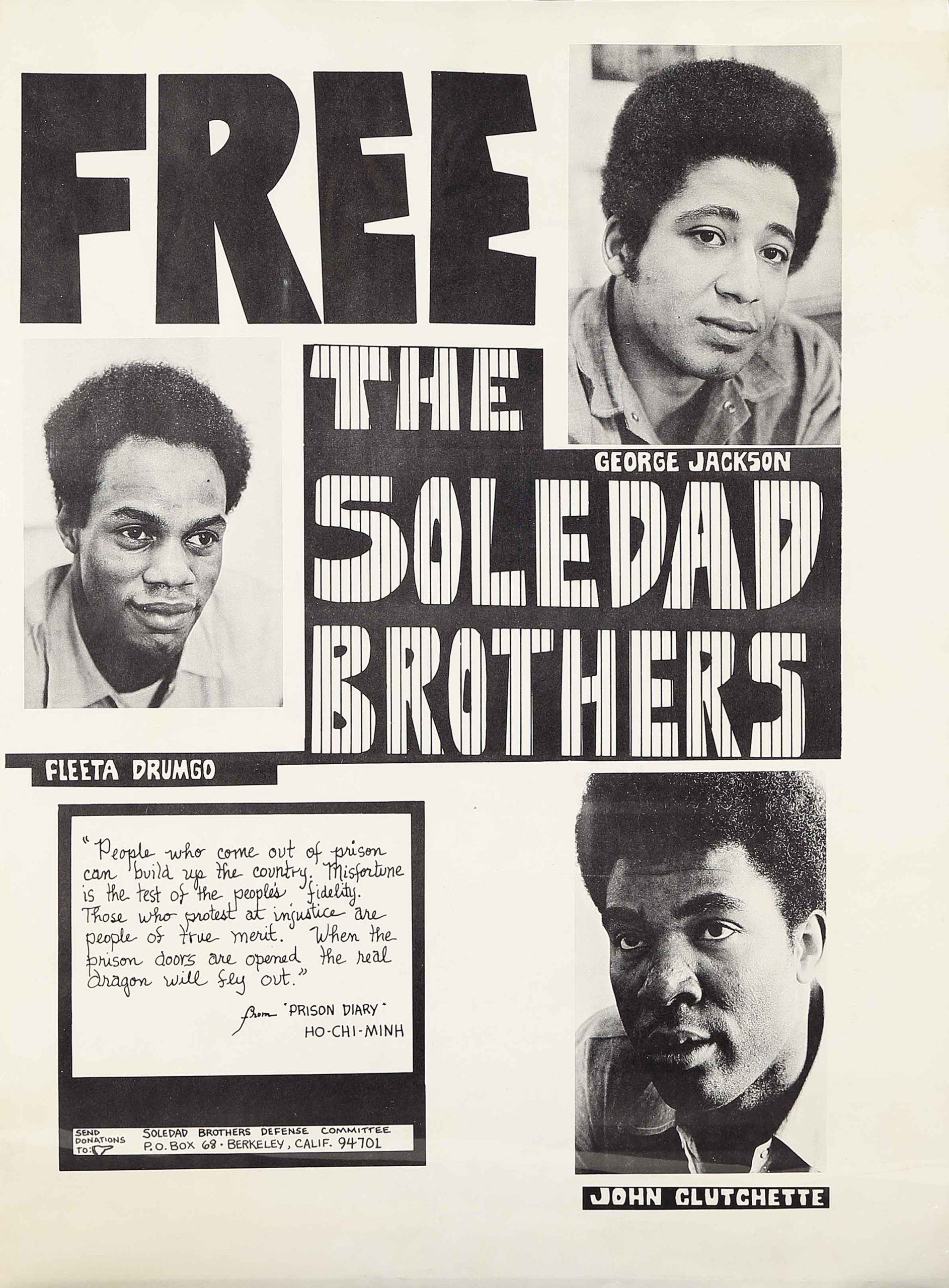

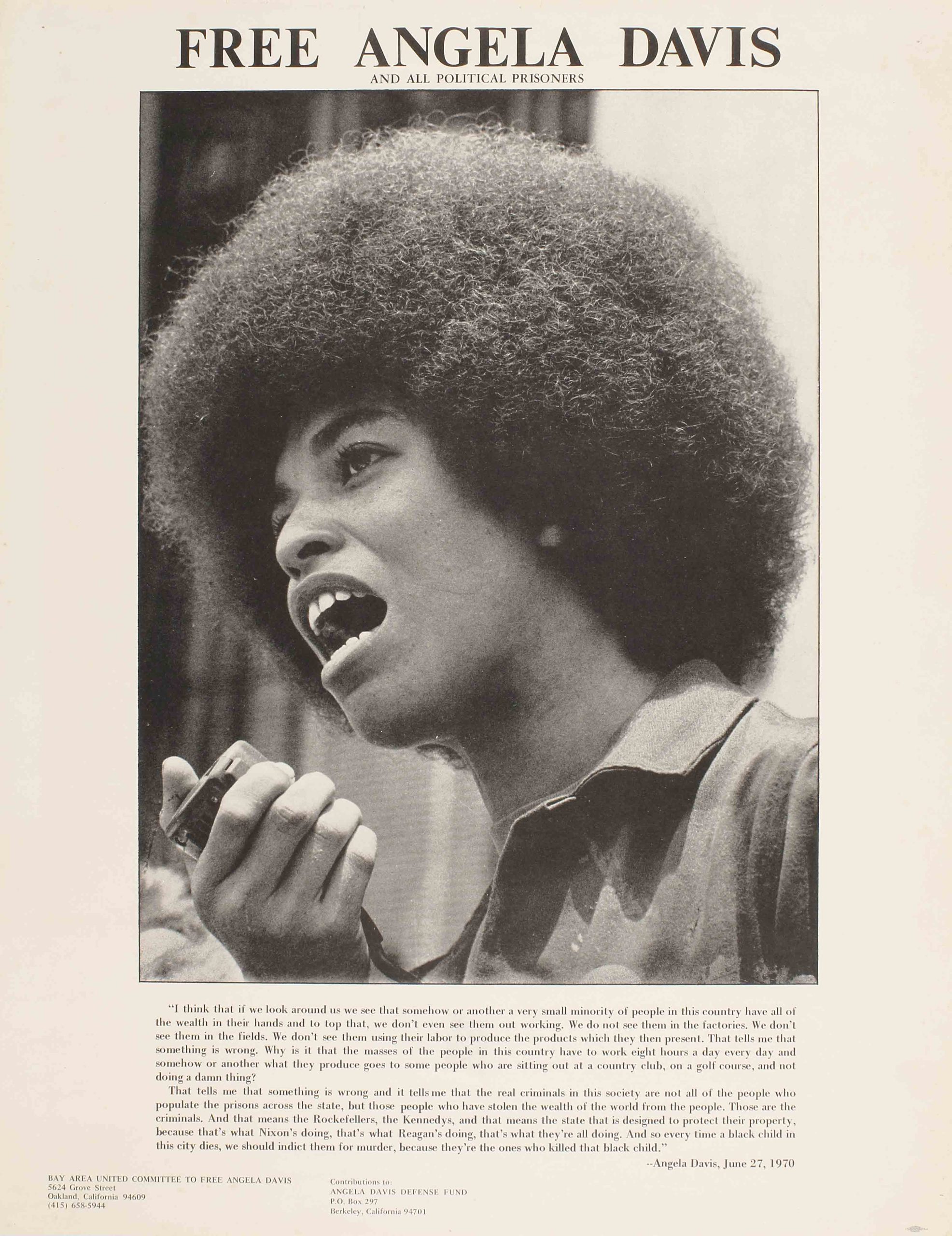

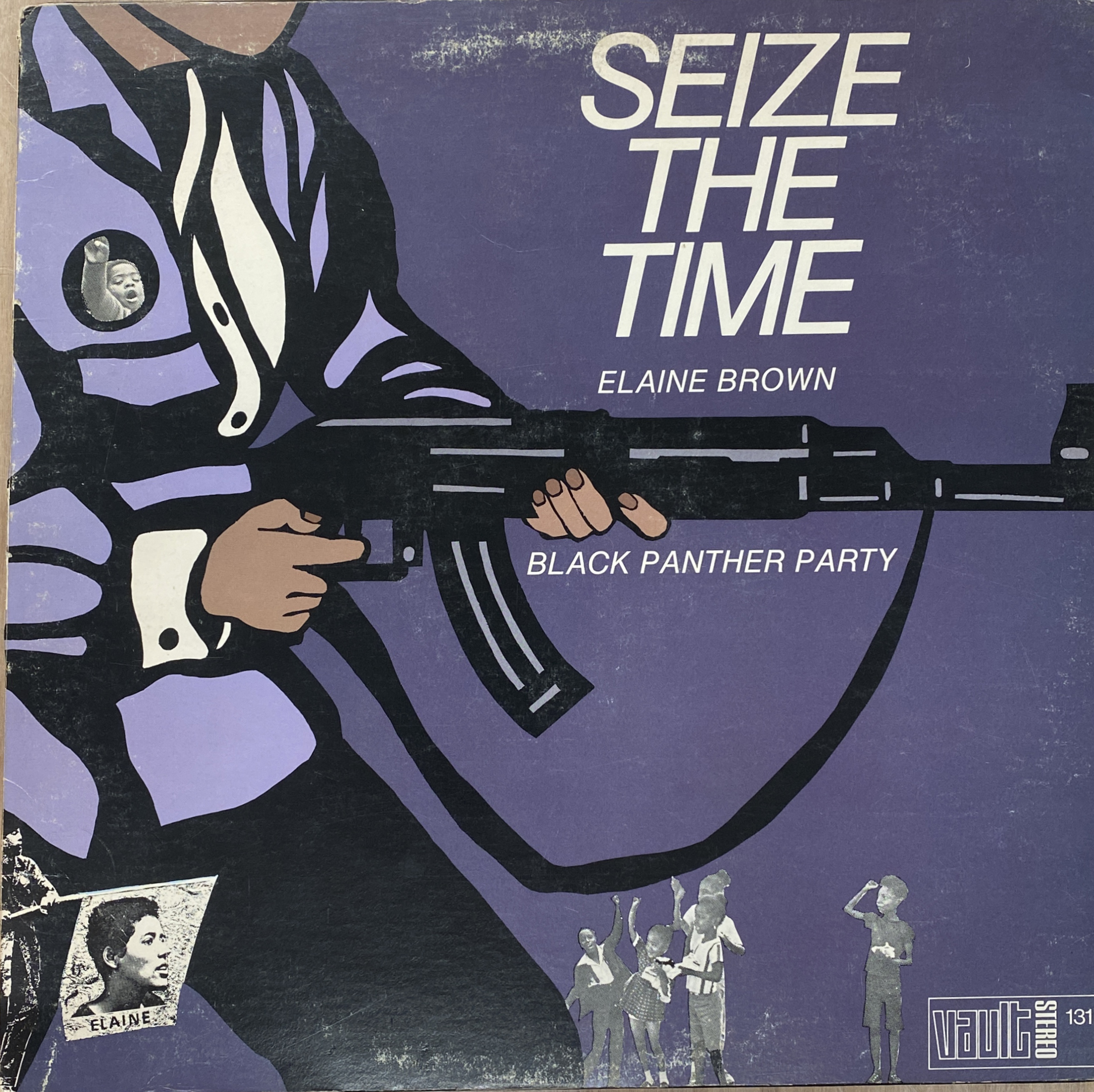

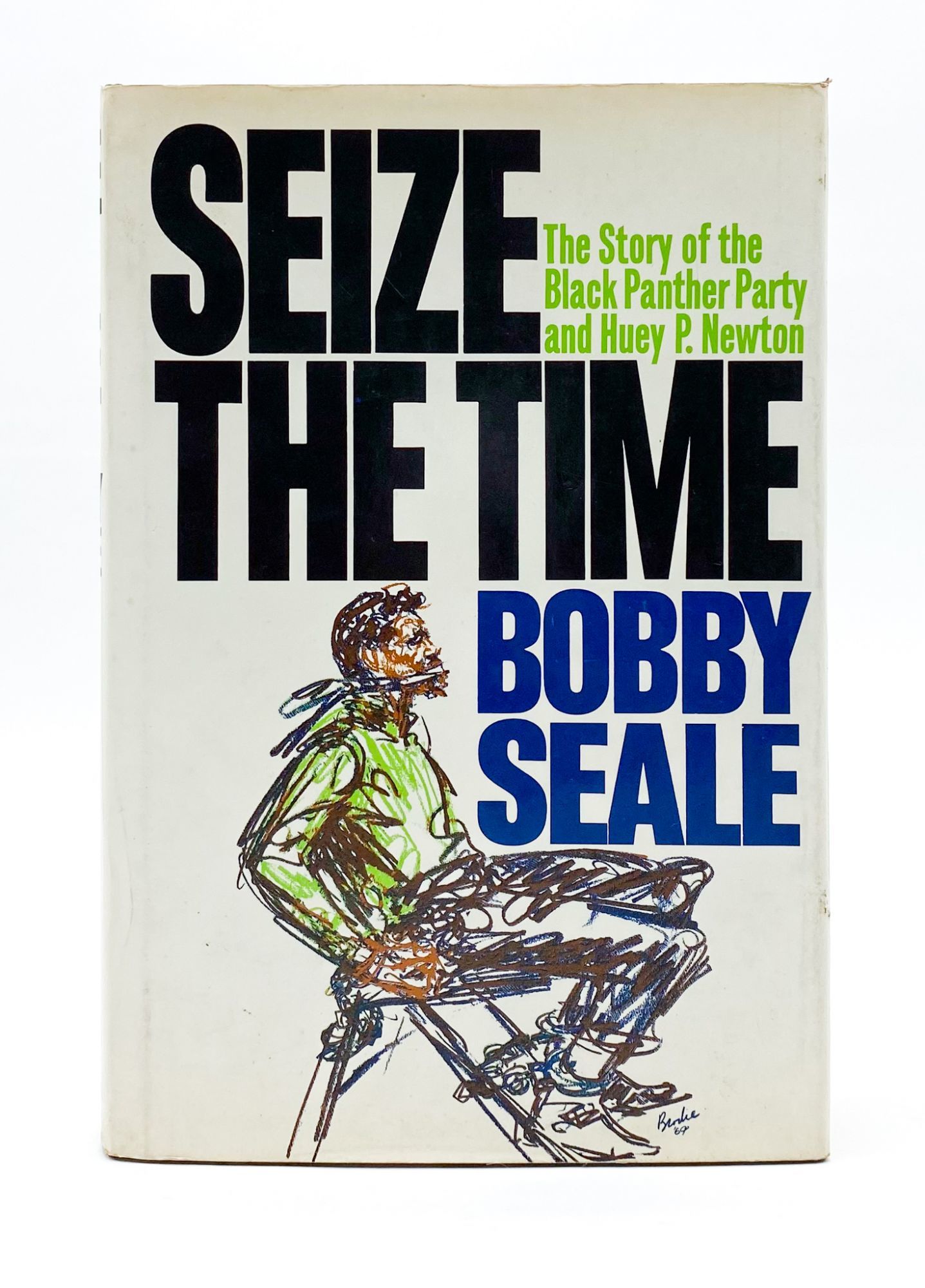

During the 1960s, the civil rights of Black Americans were among the key issues addressed by demonstrators and protesters as they confronted many of the long-standing injustices that plagued the country. A number of Black-led organizations set out to redress systemic oppression, rallying the support of their communities through a variety of creative means. In particular, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense—eventually shortened to the Black Panther Party (BPP)—emerged as one of the most influential militant groups of the time. The posters in this exhibition chronicle how the BPP devised a specific graphic language to reaffirm Black humanity and decommodify Black life. Its heroic images of party members, widespread distribution of printed materials like The Black Panther newspaper, and political campaign posters allowed it to control its own narrative and brand Black nationalism to advance a communal revolution.

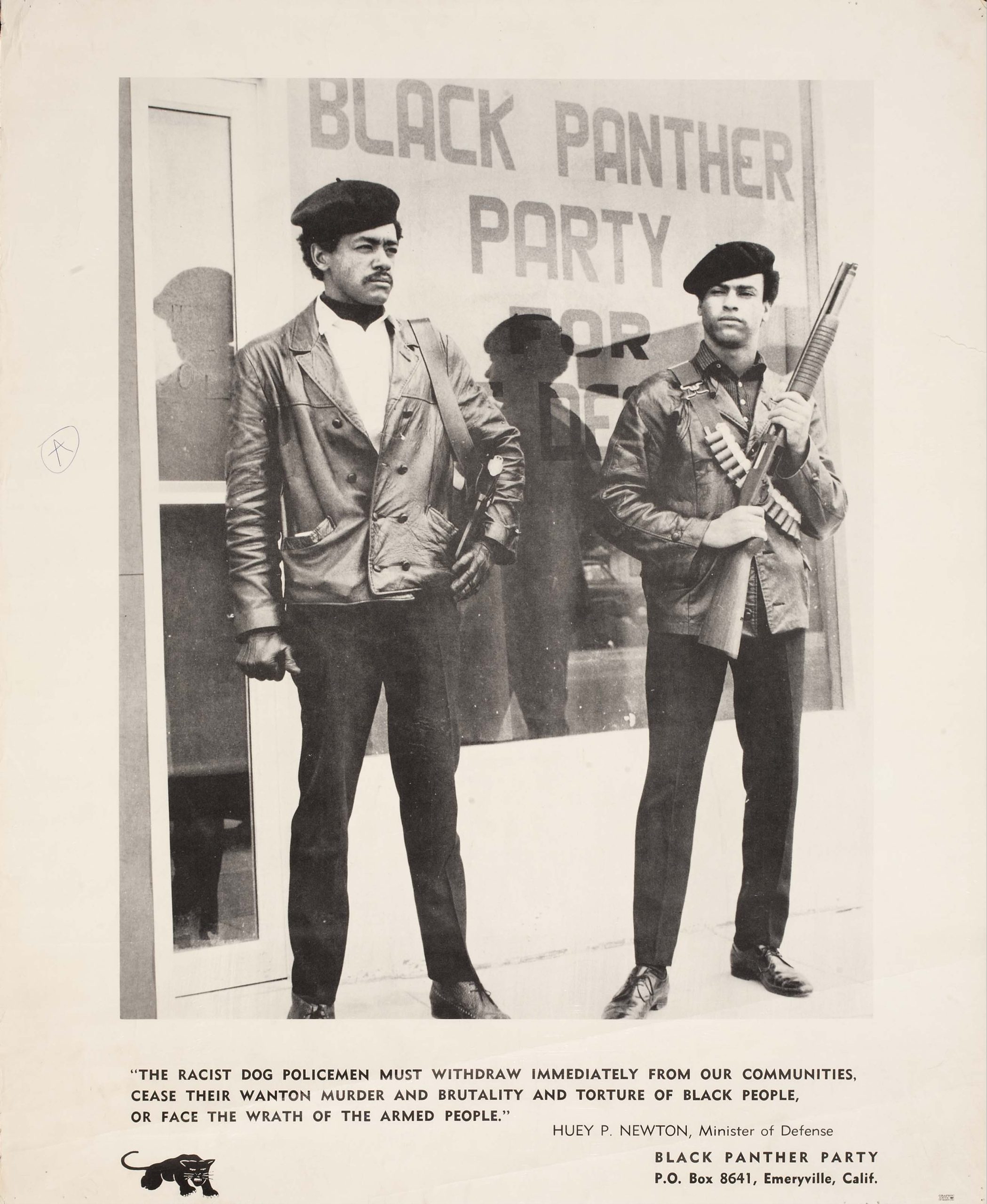

As one of the largest groups to confront the plight of Black Americans, the Black Panther Party adopted Black nationalism as an ideology, practice, and identity to mobilize the community. Proponents of Black nationalism advocated for the economic and political self-sufficiency of Black people in order to achieve liberation from oppressive systems. A Black Power platform (a form of Black nationalism) guided the BPP as it branded a new movement that relied heavily on bold language, striking graphics, and powerful photographs of its members wearing black-leather jackets and carrying exposed firearms. More specifically, the graphics and posters of the BPP became important to the dissemination of information; they effectively exposed the public to radical images and slogans that captured a shift in tone in the fight for civil rights. With an emphasis on militancy, the Black Panther Party successfully mobilized visual and written content in its posters and newspapers to further establish an authentic Black identity, responding to historic systems of exploitation and anti-Black violence.

Unless otherwise noted, all items come to Poster House through a generous loan from the Merrill C. Berman Collection.

Please be advised that this exhibition contains racist and violent imagery and language. There is also an audio component to the exhibition.