With My Little Eye: Warnings for the Homefront

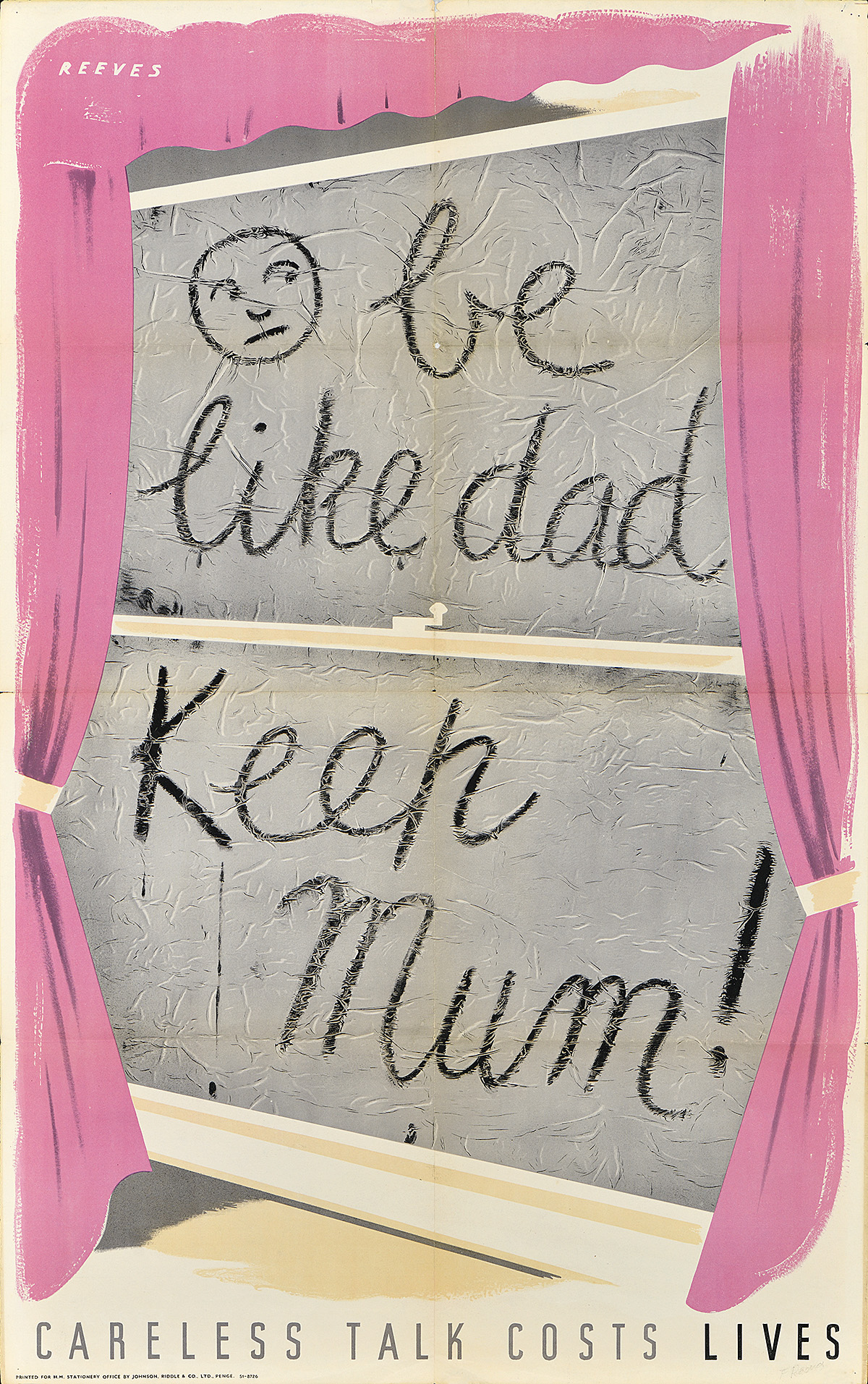

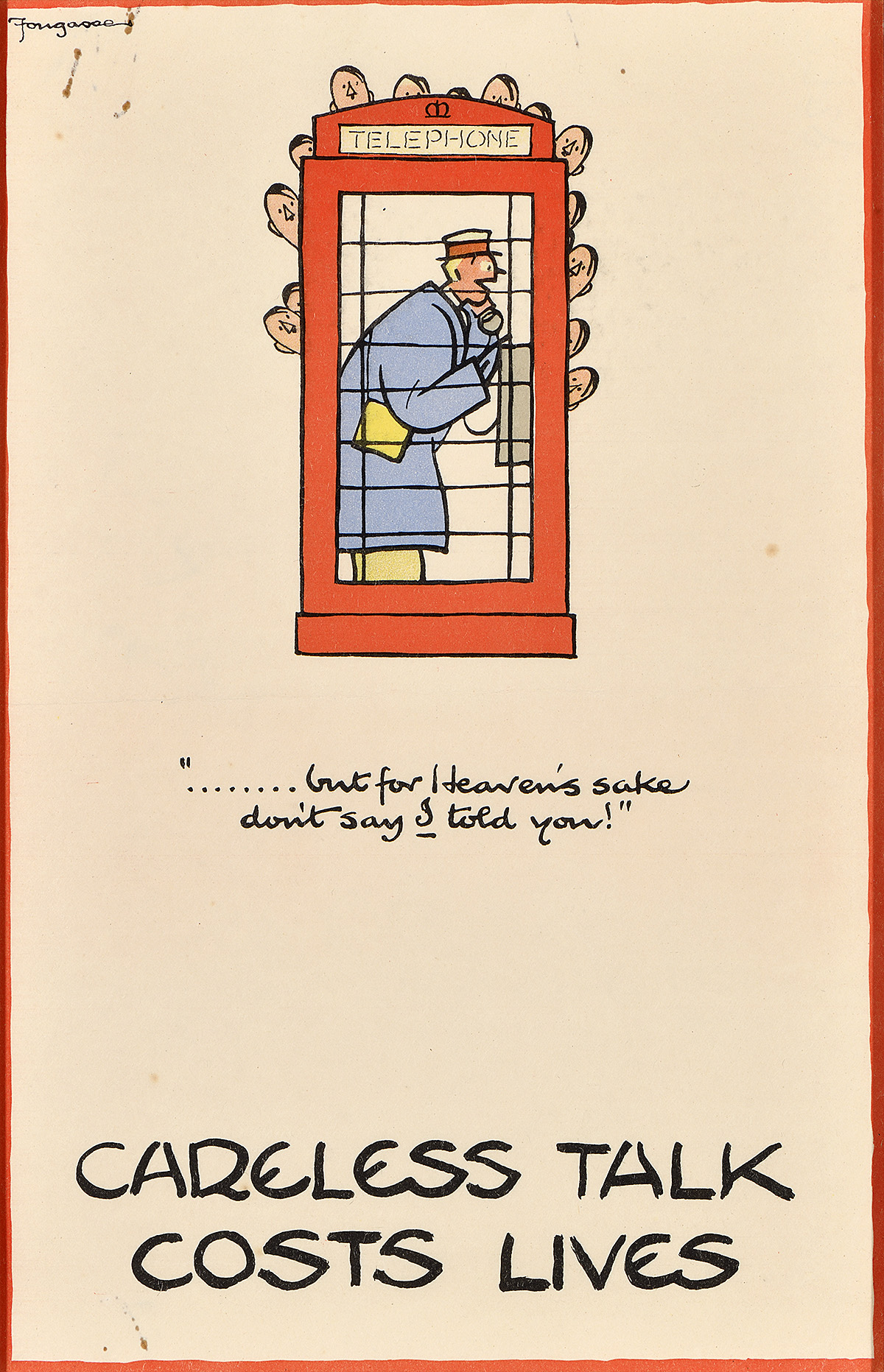

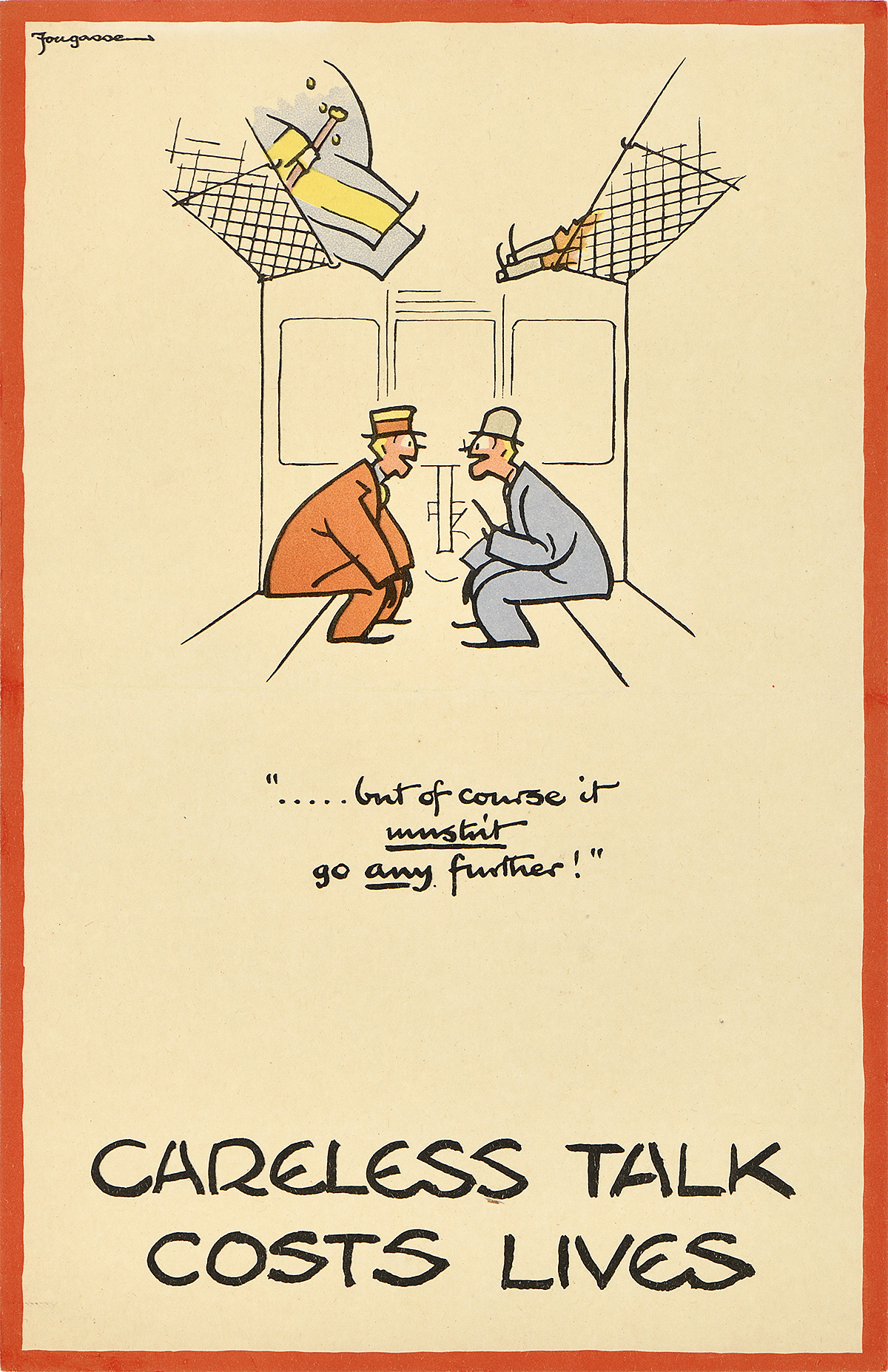

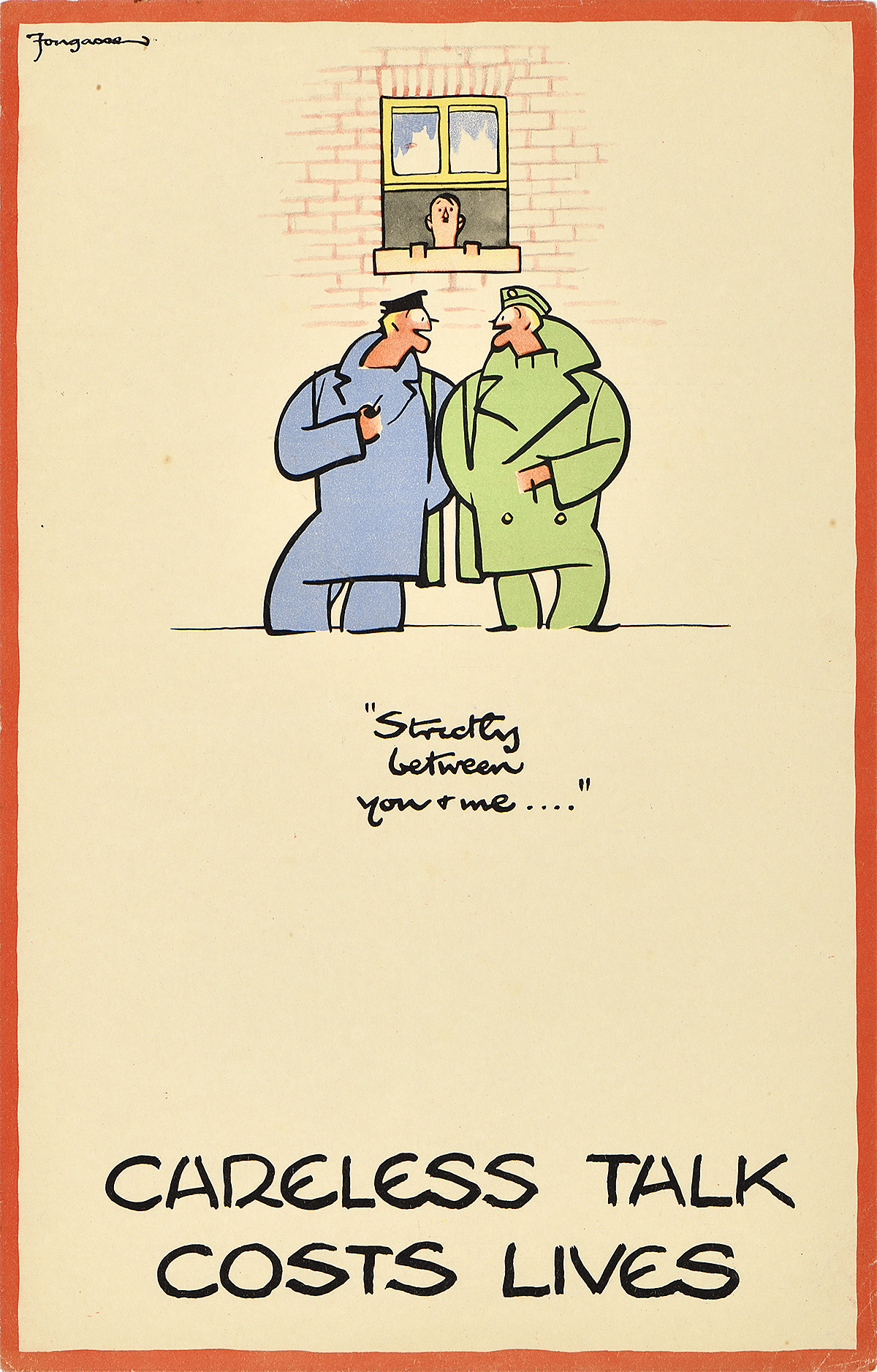

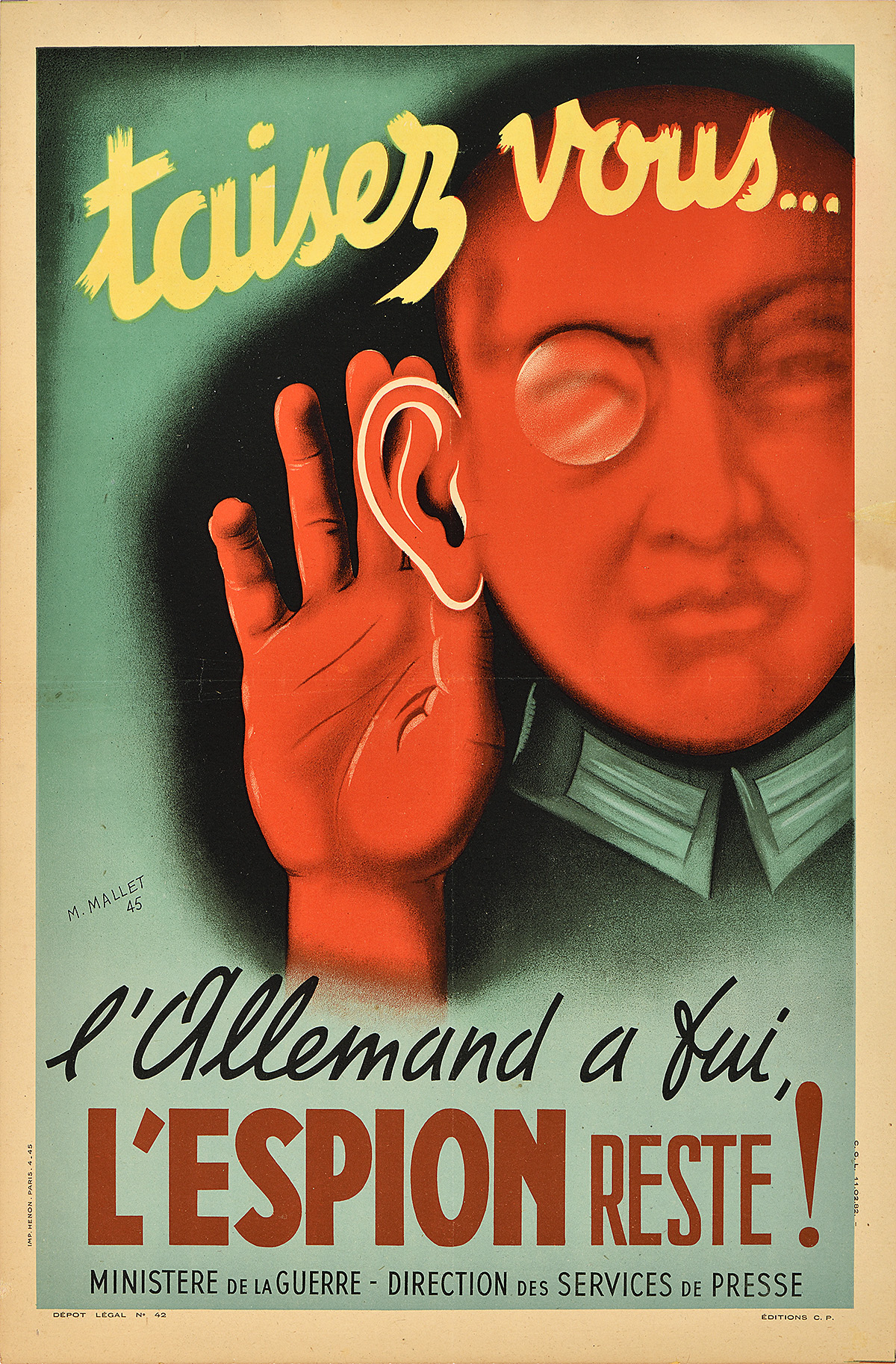

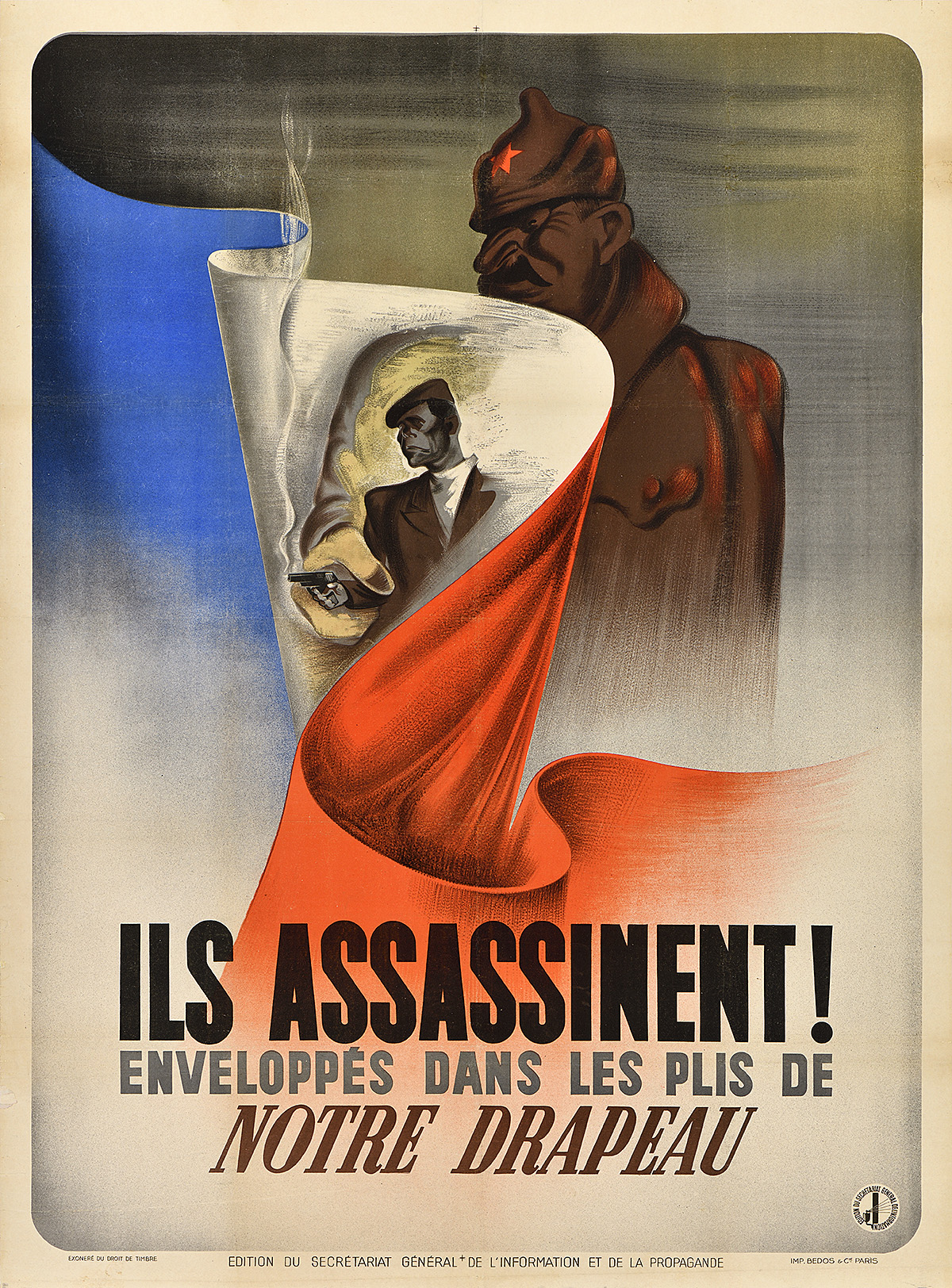

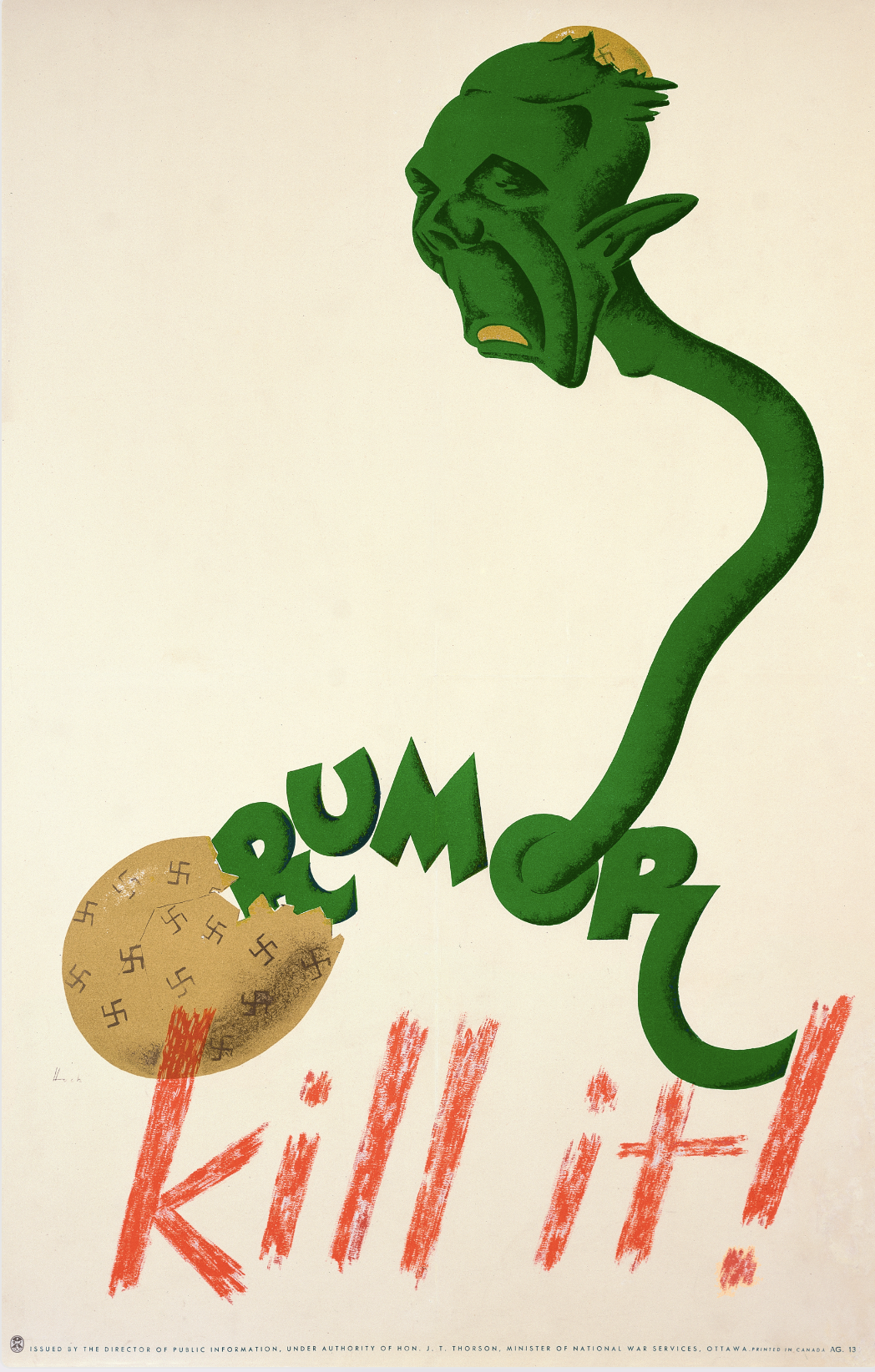

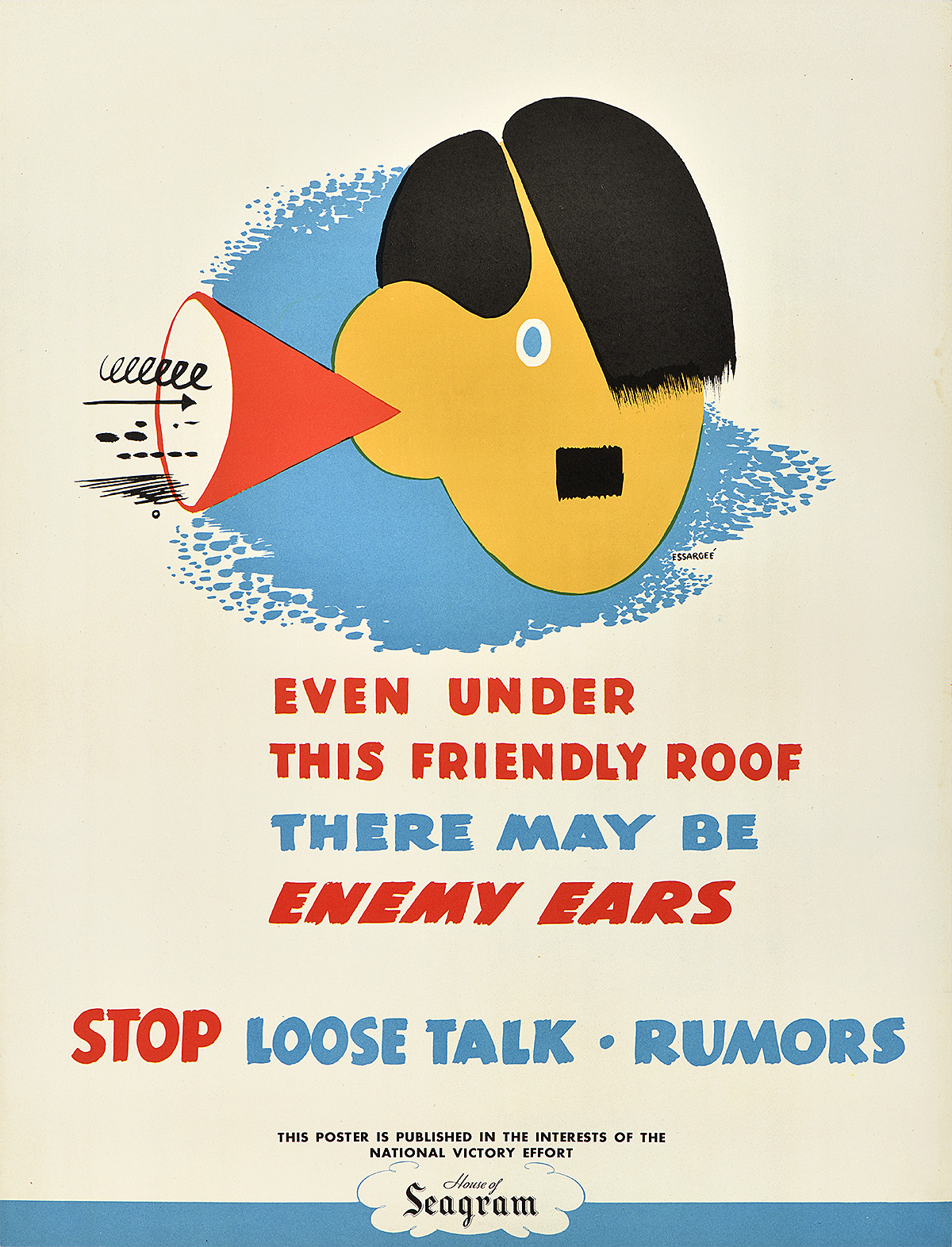

While World War II was global in scope, each country involved experienced it differently and therefore developed localized rules and mechanisms for communicating with its own population. Posters played an essential role in encouraging individuals to regulate their own behavior in the face of potential espionage. With their emotional appeals to patriotic duty, posters served both to define and reinforce national identities and characteristics at a time of crisis. They almost universally incorporated an acknowledgment of the human cost of war, inspiring citizens to “do their bit.” However this mass of posters warning of espionage presented a somewhat distorted version of reality. The popular spy-novel genre, a garrulous press, and the otherwise admirable wish of many members of the public to “get involved” contributed to a popular preoccupation with watching out for spies who were not there.

This exhibition includes posters from Great Britain, France, the United States, and Canada. The stylistic differences among them inevitably reflect each country’s individual artistic and cultural traditions, specific government directives, and its direct experience of the war. France, which was occupied by Germany in June 1940, and Great Britain, which was subject to German bombing raids from July of that year, both sustained massive civilian casualties. Their respective posters therefore focused on cheering humor and morale boosting, and, in the case of France, adapting the public to the country’s shifting political allegiances. For the United States and Canada, on the other hand, the war was a distant military conflict far from their civilian populations. Posters from these countries focused more directly on messaging that reminded the public that death was the ultimate outcome of war. In all instances, civilians were exhorted to fulfill part of their wartime social contract: vigilance against indiscretions and lurking spies.

Please be advised that this exhibition contains racist imagery.